How Do I Support Someone Who Doesn’t Want to Be Supported?

Newsletter

Thanks for reading. If you aren’t a subscriber yet, you can sign up below for free weekly posts. Paid subscribers receive additional content, for example this month’s series on teaching the whole reader, as well as the ability to comment.

Earlier this week, I met with a group of coaches over Zoom. It’s mid-October. Teachers are finalizing their SLOs. One would think that these teachers would be reaching out to coaches in their building to review their SMART goals and discuss coaching cycles.

And yet several coaches expressed frustration and concern that faculty were not accessing their support. “Maybe they’ve got it all figured out,” remarked one coach with sarcasm.

As a systems coach supporting several schools in my region of Wisconsin, I see a similar trend. Schools I know who could benefit from at least a different perspective are not engaging in coaching and similar support. I’ll reach out in person or over email, sharing exactly how I can help them. “We can develop a collaborative inquiry around the standard of main idea and key details.” They have the data and the opportunity, and yet nothing but crickets.

It’s hard not to take this personally. We feel like a failure, even though we have others engaged with us in coaching cycles. Maybe it’s us? What if my personality is getting in the way of a professional relationship? It could also be their discomfort with engaging in deeper conversations around the potential inequities existing in their context.

We can also feel a bit of envy when we hear about other coaches seemingly knocking it out of the park, for example guiding teachers and teams to examine the deficit-based language observed in their culture. Over the last two years as a coach, I have wondered on more than one occasion if I am fit to be a coach.

Once I pause and take a breath to reflect, what I conclude is that I have not yet established a strong enough relationship and level of trust with prospective clients.

I haven’t gotten to know them as a person.

I haven’t leaned in and been a true listener at key opportunities, defaulting to what I can offer them.

I haven’t “put in the reps” of connecting with them repeatedly until enough of our egos have dissolved so they feel safe to be vulnerable and honest about their challenges.

This is not something to be ashamed about. I have found it to be natural to forget about building relationships and trust. We have such limited time with our colleagues. It’s easy to jump into action and dive right into a coaching cycle without first establishing authentic connections with the staff (and ultimately students) we want to serve.

In fact, resistance to our good intentions can be an opportunity to adjust our interactions with colleagues.

“Coaches who meet resistance from teachers might interpret this as being negative and obstructive. However, we propose that resistance can signal a need for additional information, more clarity, or a different approach. It is a chance for coaches to be creative and resourceful—to build relational trust by planning activities that strengthen community, for example, or creating norms.” (Bocala & Holman, 2021)

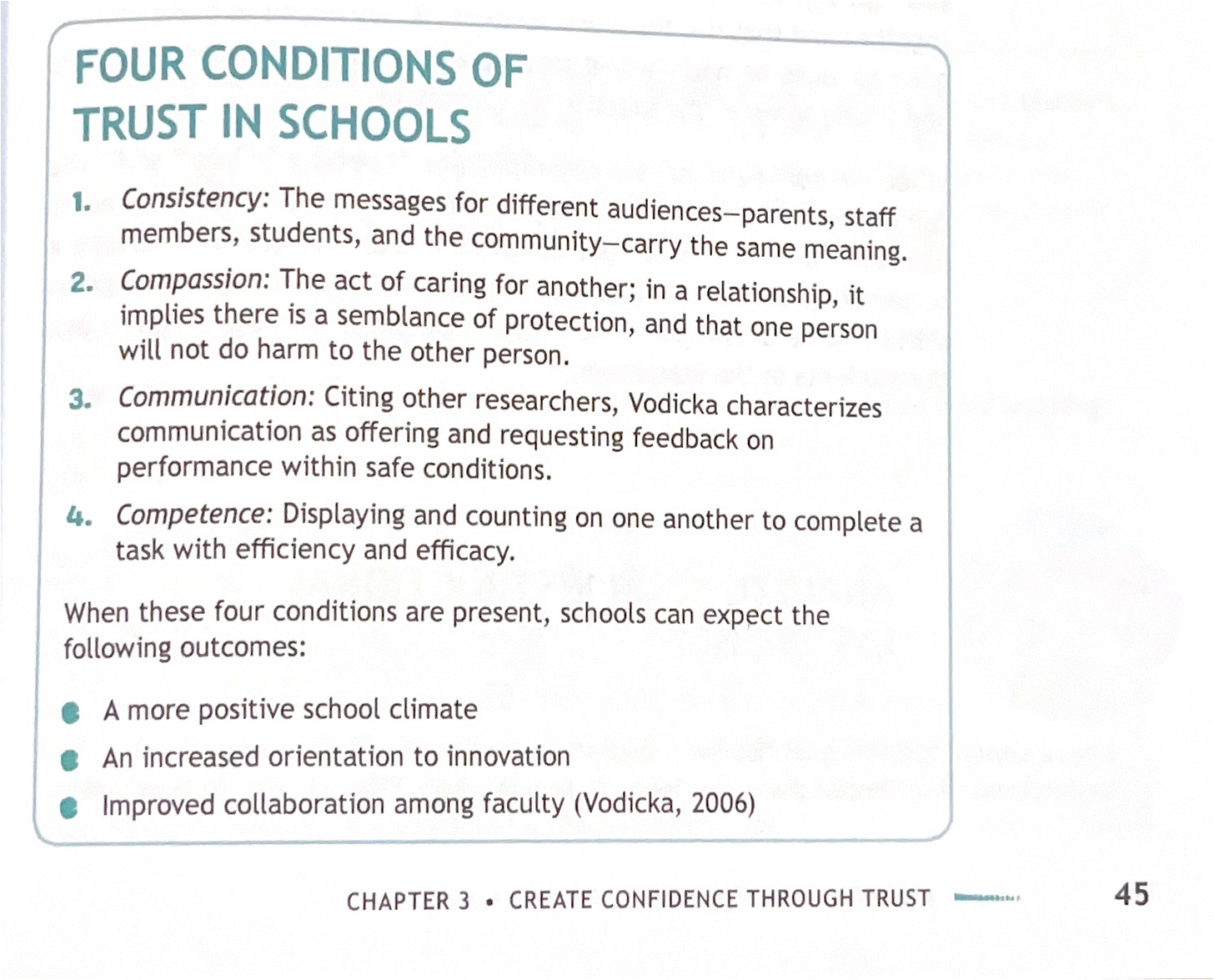

An entry point for this foundational work is the four conditions for trust. I have found the framework, synthesized by Devin Vodicka (2006), to be helpful for fostering relationships and trust.

Next are strategies (including ideas from Chapter 3 from my book Leading Like a C.O.A.C.H. that you can use today to deepen trust and relationships with faculty.

Consistency

Show up every day in classrooms. I don’t know if there is a more important recommendation here than engaging in instructional walks daily. When your constant presence is non-evaluative, teachers eventually get used to you and feel safe. There doesn’t even need to be any coaching right away. Stop in, observe, and have a short, positive conversation with teachers about what was happening. Besides a heads up via email or staff meeting that you are stopping in classrooms, there is nothing to prepare.

Make sure you are emotionally regulated. It was never a good idea for me to go into classrooms right after taking a phone call with an upset parent. Instead, I would go for a walk around the building and release any stressful energy through movement. Once I was a little more at peace, I felt I had the headspace to be attentive and non-reactive when sitting in during instruction.

Compassion

Check your biases through perspective taking. How do you know they don’t want to be supported? Because they aren’t reciprocating on your offer of support? It’s important in these situations to check our own biases as a barrier to a trusting relationship. One we can do this is by taking on the staff member’s perspective. For example, is it the end of the week when you observed them? Might they not be very talkative due to being exhausted from the long week?

Avoid fixing or solving problems. Visiting classrooms, the teachers had my full attention. Once in a while, they would want to express their frustration regarding a student or building issue. What I’ve learned is there is very little we could resolve in the few minutes together. Instead, I would acknowledge any emotions they were exhibiting (“That sounds difficult for you.”) and let them know that I will follow up later that day.

Communication

Tailor communication based on individual trust. After establishing trust through initial classroom visits, I documented observations of teaching, learning, and environmental factors. While physical notes are important, the delivery of observations and insights can vary. Teachers with whom I had strong relationships preferred detailed descriptions and reflective questions. Those in earlier stages of trust received brief notes of appreciation. All received “receipts” from my visit—artifacts to support professional growth.

Ask teachers what they wanted me to look for. When instruction walks began to feel routine, I asked teachers what they wanted me to watch for when sitting in their classroom. It was an invitation for personalized feedback. A favorite question comes from Adria Klein: “Which student do you want me to watch, and what do you want me to notice?”

Competence

Ask for permission before communicating feedback. There are times when we see an opportunity for improvement and feel obligated to share it with the teacher. In these situations, I have asked them, “Would it be okay with you if I shared some feedback?” I have yet to experience a teacher refuse this request. We all want to improve, and are more likely to grow when the improvement is on our terms.

Learn with the teachers. If we are lacking knowledge and skill with an initiative, for example a new literacy resource, we can leverage this as a strength. Let the faculty know that you are going to be learning alongside them during your instructional walks. It’s your opportunity to ask questions with genuine curiosity. You can also lean on your school’s shared literacy beliefs and instructional framework when engaging in dialogue about effective ways to use the ELA program as a guide vs. a script.

In the past, I have applied these strategies, and a few teachers still didn’t engage. That’s not a failure—that’s the reality of relational work. The outliers weren’t a reflection of my fitness as a leader or a coach. Keep showing up, building trust and deepening relationships, until they say “yes”.

What have you found to be effective in staying resilient when support isn’t immediately welcomed?

Take care,

Matt

P.S. Building relational trust takes time and intentionality—it’s not something you can shortcut. If you’re ready to create systems that make showing up consistently easier (so you can focus your energy on the relationships themselves), I work with new leaders and coaches to design sustainable practices. Sign up for a free discovery call below to talk about what that could look like for you.

What I’m Reading

Catching the Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness, and Creativity by David Lynch (Tarcherperigee, 2006, affiliate link)

A sometimes meandering yet authentic short memoir. David Lynch describes his creative process while also sharing a short history of his life’s journey. The filmmaker’s personality shines through this self-narrated audiobook - his confidence and audacity are balanced with a genuine appreciation for life.

Note: The phrase/title “Catching the Big Fish” comes from his experience of using transcendental meditation as a key tool for creativity. He speaks about it in the context of discovering ideas in the larger consciousness of the world. Lynch isn’t preachy about his practice; he simply believed in it because it worked for him.

Quotable

Matt, you hit the nail on the head when you pointed out build relationship and trust with teachers with out it there is no point. I feel trust and relationship are important if you want to have any chance of improvement in teachers. I love your reflection and sure, I would want you as a coach from reading your posts so far.