It's 1862, and the Civil War is not going well. President Lincoln and the Union Army were defeated at Bull Run and in Richmond. Low morale was commonplace among the troops.

In her book Leadership in Turbulent Times, Doris Kearns Goodwin recounts that Lincoln visited soldiers as they recuperated in Virginia - "to comfort the wounded, talk with them in small groups, bolster their morale, and sustain his own spirits."

What he didn't expect to learn from the soldiers was a key strategy for winning the war.

As President Lincoln connected with the injured, he discovered that some Confederate soldiers were able to fight because they had slaves managing their properties back in the South. They could leave home knowing that their crops and livestock would be tended to and their families taken care of.

Lincoln's priority was preserving the Union. While he believe that slavery was a "vile institution", it was the not the primary reason for the Civil War.

Yet once he understood the connection between slavery and the Union's ability to win the war, he set about to make it more difficult for the Confederacy to lean on enslaved Americans to fight.

This is how the Emancipation Proclamation came to be.

What Lincoln was practicing is what Ron Heifetz and Marty Linsky describe as "adaptive leadership".

Heifetz and Linsky use the metaphor of the theater to explain adaptive leadership:

Stage-level leadership is the "boots on the ground" type of engagement. It involves interacting with the individuals who are moving the organization forward.

Balcony-level leadership requires looking at data and related patterns to make better decisions for the organization. It's analyzing the stage level from a higher vantage point.

This concept is relevant for instructional leadership.

Most leaders strive to be in classrooms. They want their presence during instruction to be positive and informative. Under what conditions does this best happen?

A key factor is having an intention of being present. Leave any agenda to evaluate behind. Simply be aware of those around you and allow the situation to guide the experience.

Try it: Visit Classrooms With the Intent to Support

To begin, let teachers know you will be stopping into classrooms.

Your presence is best received when teachers know that you are coming and what your purpose is.

Keep your laptop in the office. If you need a notebook to write down what you hear and learn, that can be helpful. Just make sure teachers understand you are not there to evaluate, but to listen and maybe learn.

Second, write down one takeaway after each classroom visit.

Keep it brief - a phrase or a sentence about what resonated with you.

Here are some notes I took after some classroom visits.

After visiting every classroom, read through your takeaways.

Look for patterns, such as lots of time for independent reading, or lack of reading aloud. Keep doing this until you have a list of the school's overall strengths and areas for growth to share with teacher leaders and the school.

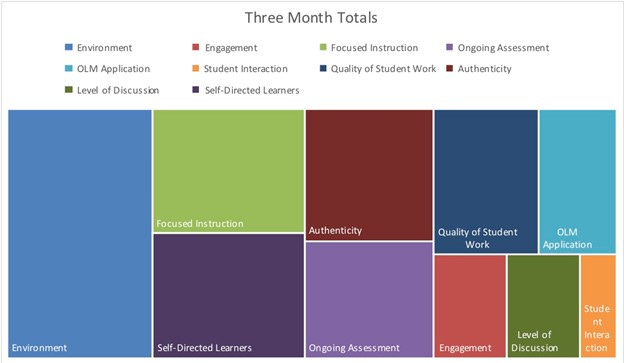

In the example below, our school data revealed that environment and focused instruction were areas of strength for us, at least based on how often they were observed. Student discussion and peer interaction appeared to be lacking.

Simply getting into classrooms is only part of leading in complex times.

Being at the stage level is important, and it's a good start.

An essential leadership strategy for the 21st century is using this information to look for patterns across the school. This knowledge can inform your professional goals and continuous improvement plan.

Related Resources

In my new course, Instructional Leadership Operating System, I provide new and veteran school leaders with ten clear action steps for getting into classrooms to better support teaching and learning. This includes “Action #10: Analyzing Your Instructional Walk Data”. It's a companion to my book, Leading Like a C.O.A.C.H. (Corwin, 2022).

Doris Kearns Goodwin was interviewed for the National Constitution Center about her book Leadership in Turbulent Times here. If you haven't read the book, the author brings some of the stories to life. If you have read it, Goodwin shares more insights about the Presidents that weren't included in her book.

Ron Heifetz and Marty Linsky wrote a guide on adaptive leadership for Harvard Business Review here. Related, this Educational Leadership article by Jal Mehta, Max Yurkofsky, and Kim Frumin connects continuous improvement and adaptive leadership. Mehta and colleagues are the source of the following...

Question for You

In your continuous improvement efforts, how are you working with rather than against the rhythms of your school?

Take care,

Matt

P.S. Juneteenth resources

Thank you, Matt. This is an insightful post—connecting the dots between leadership in all projects serving democracy, from the classroom to the battlefield. Rich implications to ponder.