I was recently sharing a slidedeck I am preparing for an upcoming reading conference with a colleague.

They asked me, “Is your presentation against the Science of Reading?” I wasn’t sure what they were referring to, until I reread the title of my presentation.

“What School Leaders Need to Know About the Science of Reading”

It was a genuinely curious question. I explained that, no, I am not against any practice or resource that supports students becoming effective and engaged readers.

Reflecting on this interaction, I think it is important to have a position on this topic. Next are some statements on where I stand with the Science of Reading.

I am against a professional’s or group’s position when they don’t practice what they preach. To engage in science, we have to be open to new ideas and information. We have to be willing to change our thinking if warranted. Too many times I’ve observed educators refuse to consider research that contradicts what they currently believe, yet say they support the Science of Reading.

I have struggled at times to come around to a new way of thinking and believing. For example, up until a few years ago I was against a core curriculum program. After many conversations with other professionals whom I respect, I was willing to implement an ELA resource. The caveat was the resource had to align with our shared beliefs. If it didn’t have time for independent reading and writing, it was out. If it squeezed out all of our engaging and effective units of study, it was out. If it didn’t provide appropriate cultural representation through authentic and rich texts and diverse authors, it was out. Maybe not surprisingly, very few programs made the final cut for consideration.

I believe we teach readers and writers first, reading and writing second. Put another way, it’s best practice to be responsive to students’ needs, to use the teacher manual as a guide, and to not assume that a resource is aligned with the appropriate standards or culturally relevant issues. My priority list, in order of importance: students, standards, then stuff. There’s nothing scientific about teaching from a script.

Students need to be reading whole books and a wide variety of texts independently. Books and other rich texts shouldn’t be treated as an appetizer or dessert; they are the main course, not excerpts. A program that supports this end is a worthy one.

I believe teachers are most effective when they teach skills and strategies in the context of integrated, engaging literacy experiences that build their identities as readers and writers (and communicators and thinkers). The professional literature overwhelmingly shows that an integrated and comprehensive approach to literacy instruction is best practice (Afflerbach, 2022; Fisher & Frey, 2011; Forzani & Bean, 2023; Gabas, 2023; Ivey & Johnston, 2015; Schmoker, 2018; Valencia & Ruly, 2005).

If students don’t leave your classroom wanting to read more than when they came in, then whatever approach or program you were using was not scientific. Why teach them to read in the classroom if they won’t read outside of it? The evidence is in the outcomes if we are willing to observe and ask students.

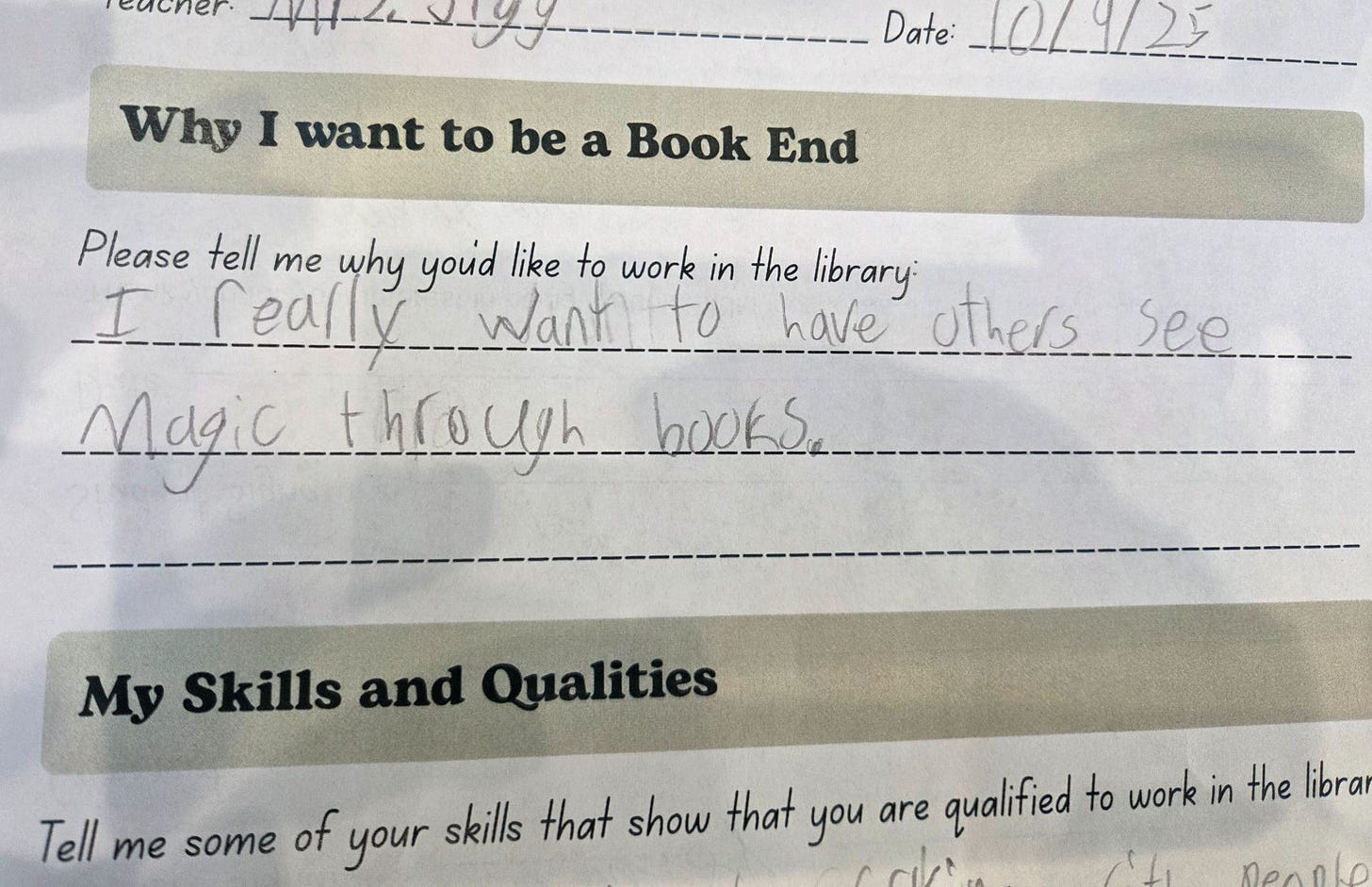

As an example for this last point, the former librarian I worked with is currently taking applications for students to join the school’s Book Budget Club. This group is allocated a budget to improve the school library selection. (See here for a previous article on this project.) The librarian, Micki, shared the following response with me from one of the applications.

This response reminds me of what science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke said about science.

“Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”

I am not interested in proclaiming whether or not I support the science of reading. I am for scientific thinking, not dogma. I am interested in ideas and issues, projects and possibilities, that continue to move us toward a day where all of our students have access to highly engaging and effective literacy instruction.

What I’m Reading

The Bone Clocks by David Mitchell (2015, science fiction, Libby) is a reread for me. This epic novel spans across 60 years, starting in the 1980s and ending in the mid 2040s. The protagonist, Holly Sykes, has psychic abilities. This talent is of interest to the anchorites, a group with similar skills who feed off the living to reincarnate and keep themselves young. Holly’s story is told through a wide number of perspectives, each person connected to Holly in some way with distinctive personalities.

Reading fiction like this, you can see what’s possible with books: the spiraling narratives, how one decision can have ramifications on multiple future situations, and the importance of never giving up your agency or principles. It’s nothing short of magic.

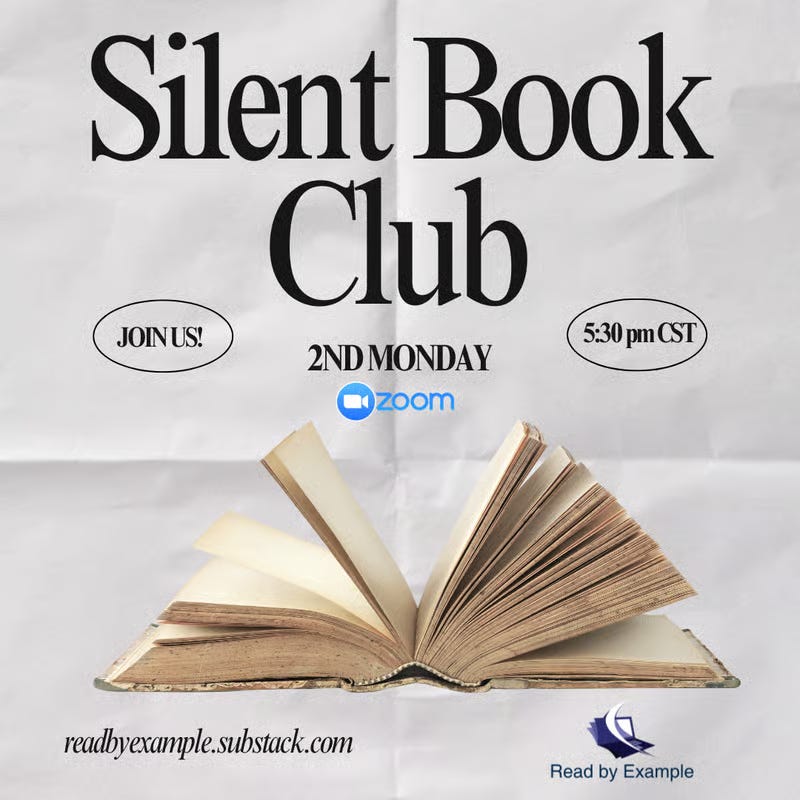

Join Us for Our First Silent Book Club!

This inaugural event is open to all readers.

Date: Monday, October 13, 2025

Time: 5:30pm CST

Location: Zoom

So clearly and authentically written Matt. I appreciate you. Your wisdom and gift with words are a blessing to those in the education field. Your advocacy is noted and so very appreciated.

I always love what you have to say, but this article has to be in my top favorites. I’ve been in conversation with others recently about the very ideas you talk about. It’s heartening to know that there ARE others out there who believe in student choice, teacher decision-making, and the power of authentic reading and writing experiences. The science matters, and it matters a lot. But not just a narrow body of it—a wide breadth of it. So does our own classroom experience. It’s in the teaching of real kids every day, outside of labrartory settings that much of the research was conducted in, that brings the nuance to the science conversation. Thank you for continously speaking for our students!