Classroom Libraries: Who Owns the Reading?

Article

“You are welcome to check out books as long as you are reliable.”

I had been looking at the library in the church, a few minutes before mass started. We weren’t at the church in which we belong, one in a neighboring town. The parish librarian noticed what I was doing and offered this comment.

My first thought was, has anyone confided to this person that they are, in fact, unreliable? Thankfully I bit my tongue as the librarian demonstrated how to check out a book.

This parish library was nicely organized by topic and author. Not a title out of place. The process of borrowing a book was clear.

And yet I left without a book. I didn’t feel comfortable checking one out. Why? Because the library belonged primarily to the librarian.

To be fair, they never said this, but they didn’t have to. It was in their actions and language that communicated to me that this nicely organized library was to be appreciated more than used.

Understanding Classroom Libraries

In our school, we are creating language about schoolwide expectations for how students should be involved in designing and organizing classroom libraries. We want our kids to believe that books belong to the reader.

Why classroom libraries? Proximity, for one. In Readicide: How schools are killing reading and what you can do about it, high school teacher Kelly Gallagher describes recommending a book from the school library. Only one student checked it out. He then brought copies to the classroom and made another pitch. They were checked out immediately. A waiting list was needed.

Classroom libraries are not a replacement for the school library. They should complement each other in support of authentic literacy experiences.

Classroom libraries should invite students to read. Kids should feel comfortable perusing books for independent reading and reading at home. Subsequently, the teacher can take advantage of these opportunities for instruction, such as conferring with students as they read books of their choice.

Why Involve Students in Classroom Library Organization?

Regie Routman, a longtime reading teacher and educational consultant, advocates for classroom libraries as “the cornerstone of a literacy classroom” (2003):

Classroom libraries are a literacy necessity; they are integral to successful teaching and learning and must become a top priority if our students are to become thriving, engaged readers.

Not only should classrooms have robust libraries for kids, but Routman also supports students becoming directly involved in the design and organization of them.

When students help create the library, they use it more. Too often, we teachers do all the work. Not only does that take lots of teacher time that could be better spent elsewhere, but also students are less likely to find material they like, which, in turn, affects how much they read. I have watched some teachers work hard to create lovely looking libraries. But they organize these spaces for themselves, and the books are often not easily accessible to students—in terms of the types of reading materials that have been chosen and the way they are displayed and located.

Why don’t more teachers and principals advocate for this involvement? Routman references this - “we teachers do all the work” - which leads one to wonder who truly owns the reading in classrooms.

So, how do we release some of this responsibility? What might happen if we do? Routman notes the engagement benefits we see with students when we include them in this practice.

However, once teachers give up some control and let their students help make the decisions, pleasant surprises await. With demonstrations and guidance, even first graders can take full responsibility for categorizing, sorting, and organizing books and returning them to agreed-on places—and they love doing so.

Recent research supports moving beyond simply putting books into a classroom. Yi and colleagues (2019) discovered that while bringing in texts into a classroom can have benefits, such as students checking more books out and reading outside the school day, access to texts alone was not enough. A few conclusions:

No increase in authentic instruction during independent reading time.

No expectations for reading independently.

No effect on student reading achievement.

In other words, simply putting books in a classroom may not lead to better readers. Students need the support that only an effective teacher can provide. When we use classroom libraries as teaching tools and leverage this literature to advance student reading engagement and achievement, only then does the investment seem to pay off.

But I don’t have time! (Ten Strategies for Involving Students in Organizing the Classroom Library)

Time appears to be the number one factor for why educators do not include students in developing the classroom library. (It’s also the main reason teachers don’t give students time to read independently.) Given this real concern, consider the following ten ideas for involving students in organizing and maintaining the classroom library.

Students select titles from the book order for the classroom library.

Have students bring books from home that they want to share with peers.

Distribute gift cards from local bookstores for families to buy books for the classroom library.

Bring in “mystery readers”, usually family members, to bring in a copy of a favorite book to read aloud to the class and then donate it to the library.

Include student-authored texts as prominent parts of the classroom library.

Students audio record themselves reading aloud books in the library, then attaching a QR code link of the recording to the book.

Write short book reviews (instead of book reports) for titles in the library.

Start the year by completely re-organizing the classroom library, as a community-building activity and for everyone truly own it.

Provide a space for students to post sticky notes that list requested titles.

Include book club bins as part of the classroom library.

What are we doing for our students that they can be doing for themselves?

- Diana Laufenberg

References

Gallagher, K. (2009). Readicide: How schools are killing reading and what you can do about it. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Routman, R. (2003). Reading Essentials: The Specifics You Need to Teach Reading Well. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Yi, H., Mo, D., Wang, H., Gao, Q., Shi, Y., Wu, P., ... & Rozelle, S. (2019). Do Resources Matter? Effects of an In‐Class Library Project on Student Independent Reading Habits in Primary Schools in Rural China. Reading Research Quarterly, 54(3), 383-411.

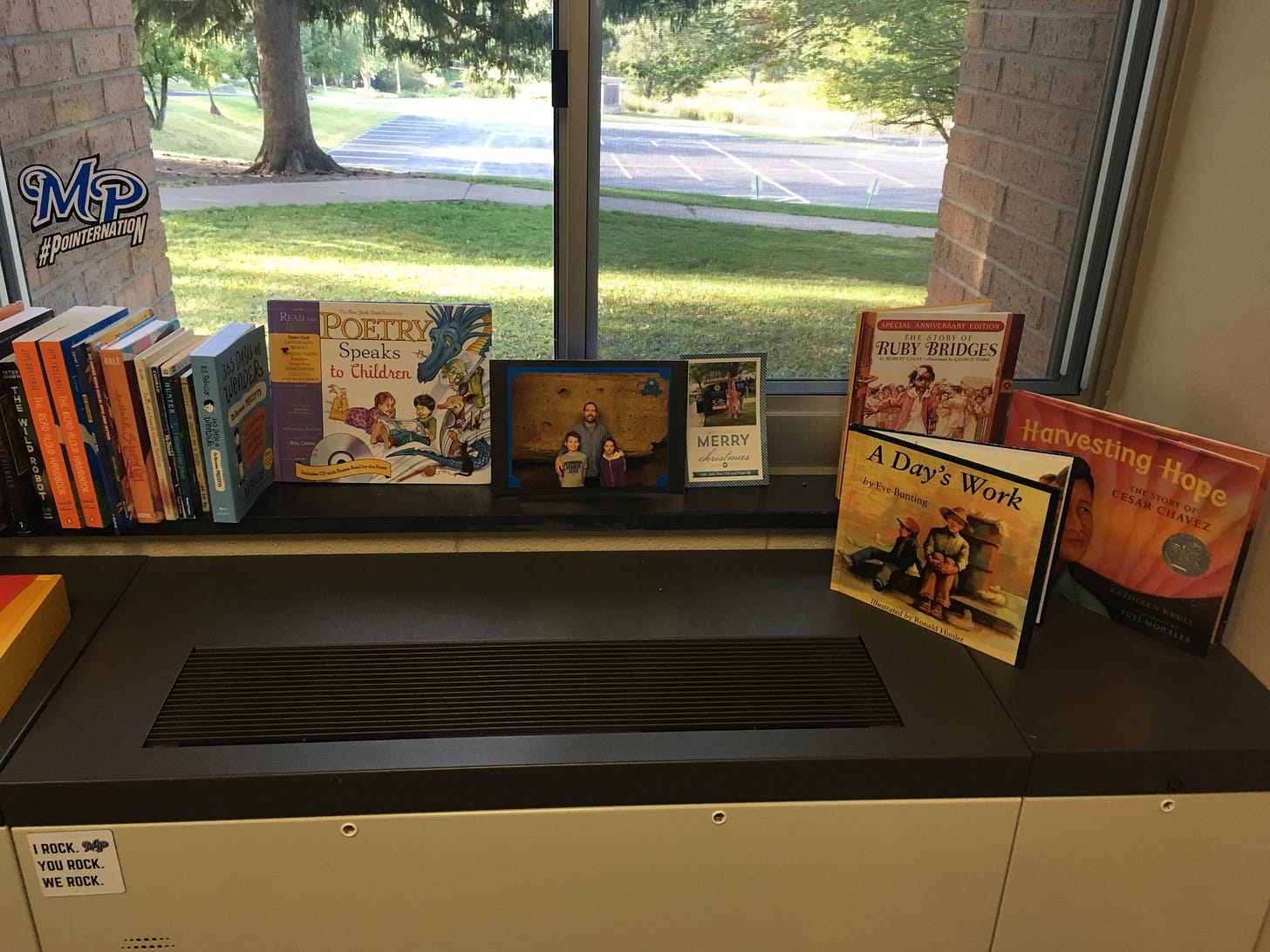

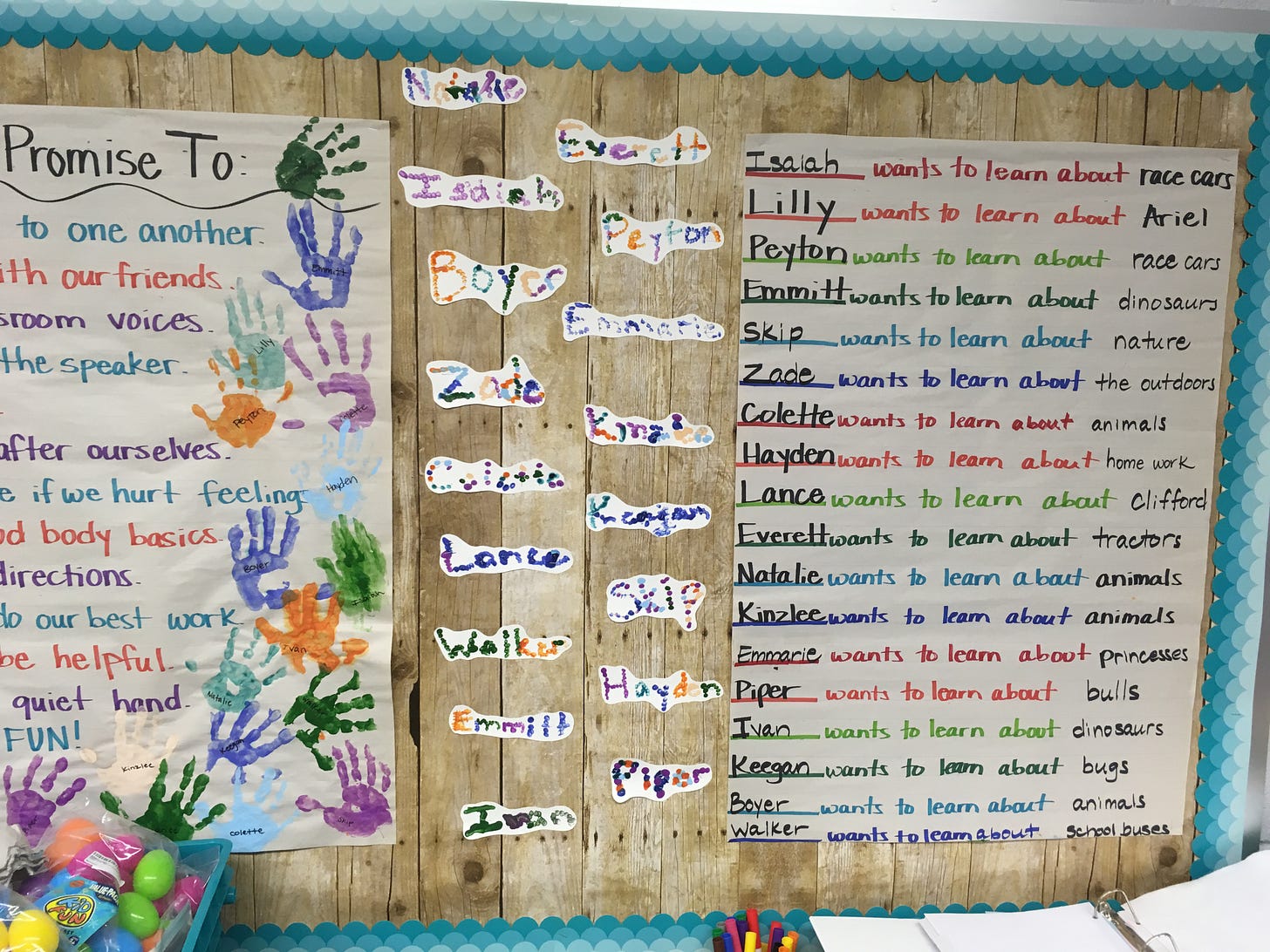

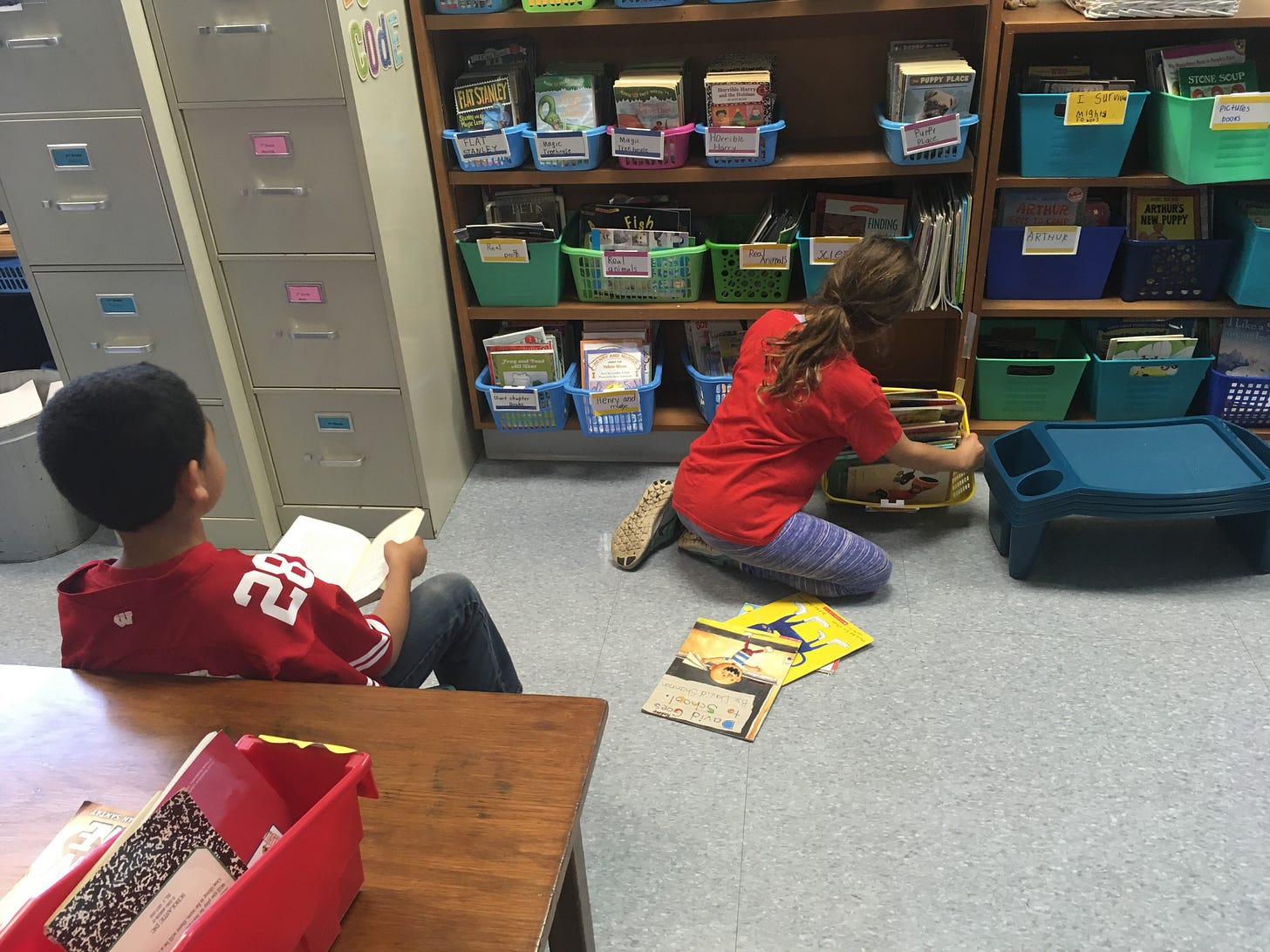

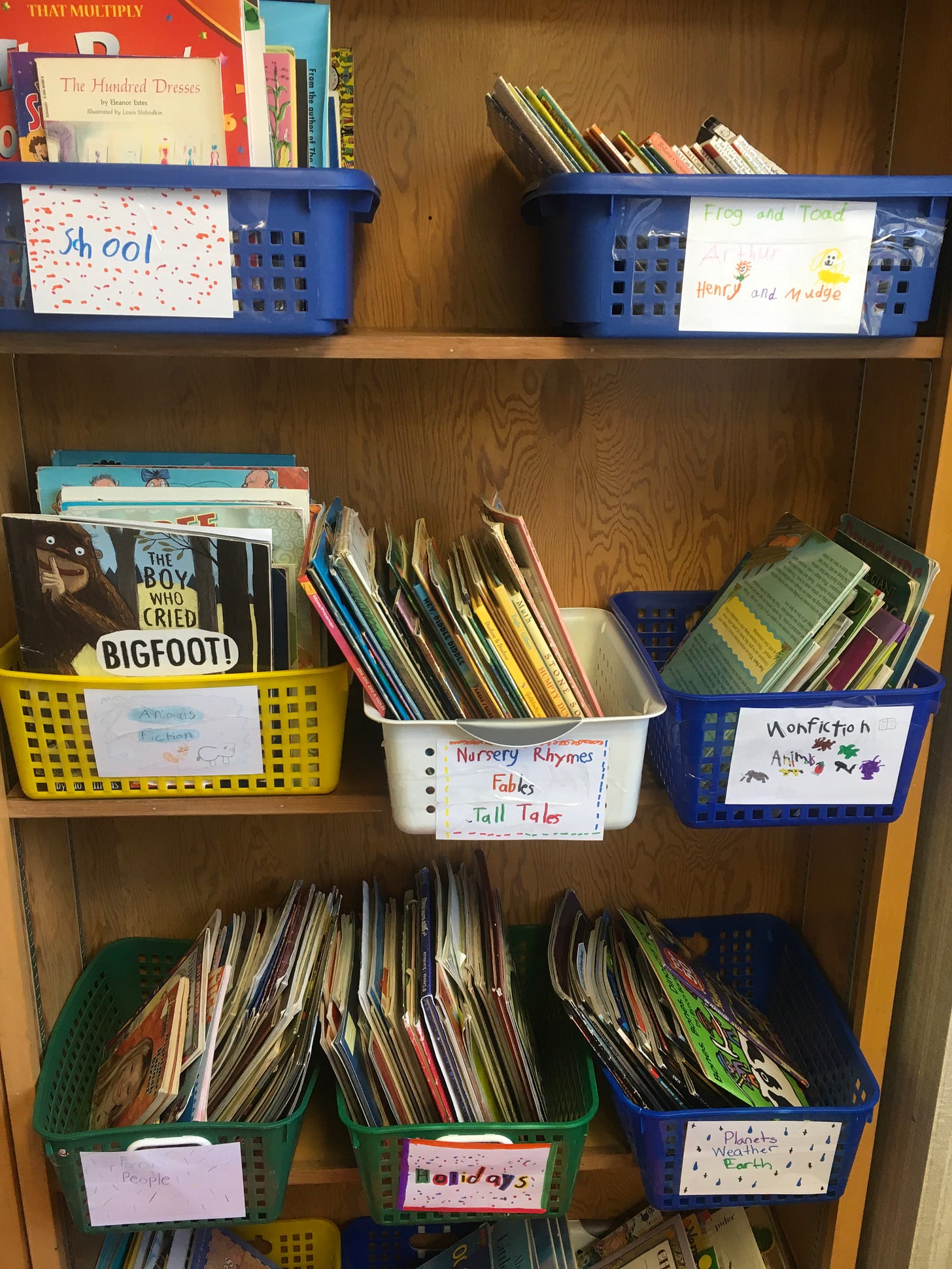

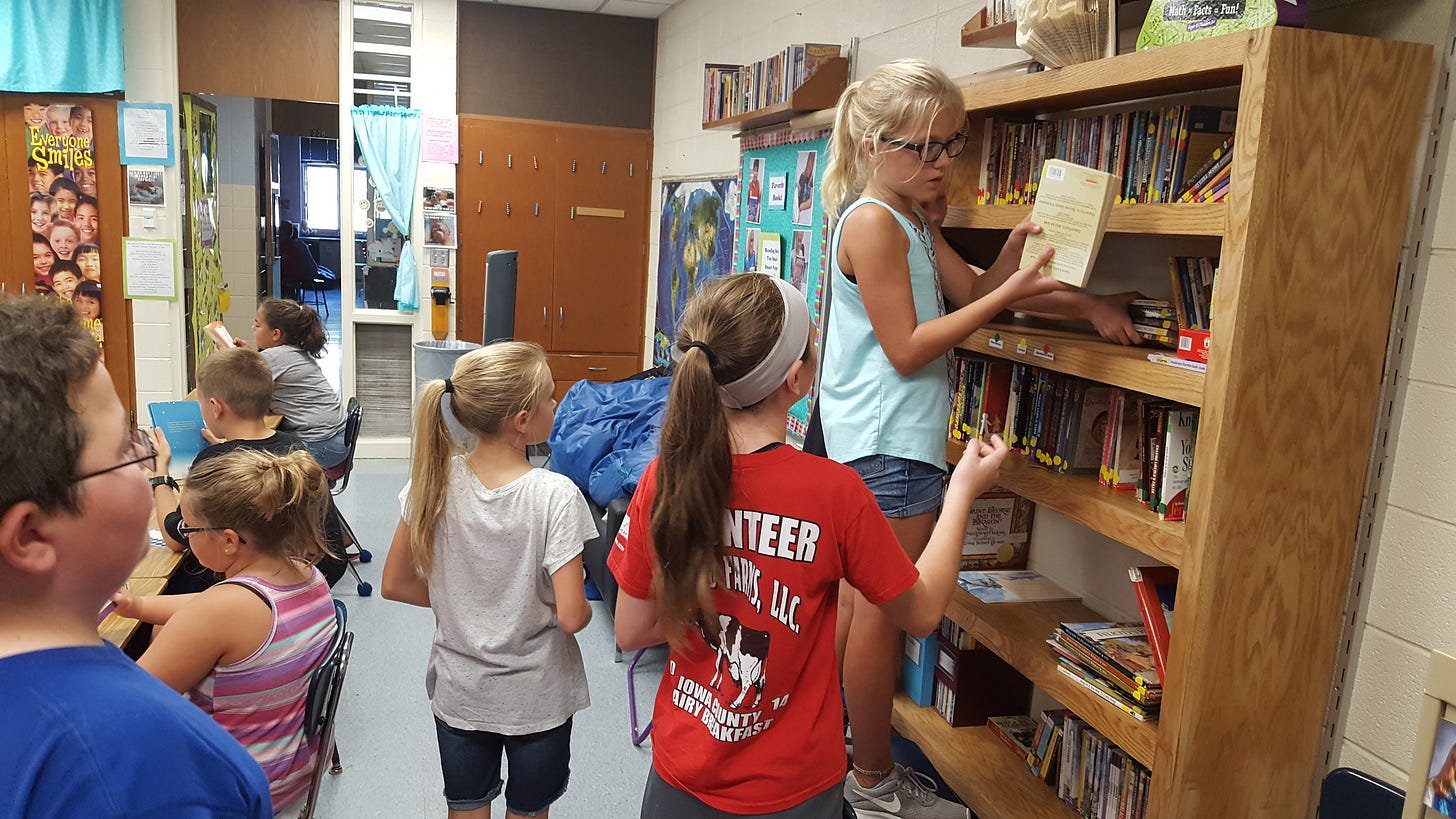

Below are images, a crosswalk of our PK-5 school, in which strategies for involving students in the design and organization of classroom libraries are being implemented. Also, click here to view slides from our schoolwide discussion about this journey.

A preschool classroom library with student-authored texts

Kindergarten students tell their teacher what they want to learn about this year, to inform future purchases for the classroom library

1st graders deciding together how to organize the classroom library texts

2nd graders maintaining the classroom library during the school year

3rd graders creating the labels for the classroom library bins

4th graders maintaining the check out system for their classroom library

5th graders re-organizing the classroom library to suit their needs

My “office library” with a variety of literature for kids