Conferring with Readers and Writers: A Drive-Thru Assessment or a Sit Down Conversation?

Article

Classroom libraries are essential for developing engaged, successful readers and writers. Time for daily independent reading and writing is equally important. So what’s the role of the teacher? To support students. Conferring can be that scaffold.

Once this belief is shared, I have found that teachers will often go to the following question: “With conferring, how can I support all of my students?” This naturally leads to the biggest challenge: time.

Publishers seem to respond to this worry by offering programs and tools that maximize teachers’ time while ensuring contact is made with every student. But is that actually helpful? Are we responding to what kids need when we value quantity over quality?

A Metaphor: Two Types of Meals

During the sports seasons, my son and daughter sometimes seem to be heading in different directions. One has soccer in DeForest while the other is at a cross country meet in Baraboo. As you can imagine, mealtime is a rush. We might pull into the Culver’s drive-thru so we can get to the next event.

A drive-thru dinner works in a pinch. But it’s not the way I would want to have every meal with my family. We don’t make eye contact. Our conversations are brief. To be honest, I am not sure how much I really enjoy the food. It’s fuel for the next trip.

Sitting down for a meal is preferable. We spend time together around food and have so much more to say. I can see what might be exciting or bothering our kids by their body language as well as what they are sharing. They feel listened to and supported and I am a better parent for it. Our attention is on the other and in the moment instead of thinking about that next thing.

To bring home the metaphor, conferring is at its best when we are not rushed. We bring our whole selves when we devote time to our conversation with students. The same aspects of communication, verbal and nonverbal, prove essential. It’s a reciprocal relationship in which both parties become smarter while fostering relationships.

Understanding Student Conferences

Conferences are the conversations between a teacher and at least one student about their reading or writing. The purpose is to assess and instruct students. Conferring is the assessment action we engage in with students.

Jennifer McDonough and Kristin Ackerman offer a nice description of conferring as formative assessment (p. 3):

Conferring is a time to differentiate our instruction to meet a child’s particular needs. Instead of relying on the child to actually listen during a whole-group lesson and understand it, we can say to the child, “Here is what is working for you. Let me show you something that will make it even better.”

You will find this approach depicted in the two examples provided later in this article.

Conferring is “personalized assessment” as it guides both teacher and student within the context of authentic reading and writing. Regie Routman has extolled the benefits of one-on-one conferences for some time. She recalls a conference with Maria, a “fake reader”, during residency work in one school (p. 222).

I was flabbergasted to realize that she could barely read. She had been in that school for several years, and in spite of caring teachers and the fact that she had been sitting with books every day for sustained periods of time during independent reading, she couldn’t read anything but the very simplest text. Here is a crucial point: deliberate practice without effective teaching and coaching doesn’t guarantee growth. In fact, students can stay stuck for years without much improvement.

Conferring is critical for literacy success. It can create that essential link between what we teach and what we expect students to learn.

A conference can be informal, such as roving conferences during readers-writers workshop. It can also be more formal, with a management plan in place and specific goals a teacher might want to accomplish with their students. In the next two sections, you will find an example of both an informal and formal conference.

Informal Conference with a 1st Grade Writer

The student had used an ellipse in his writing (the “…” in a sentence). For 1st grade, this was a big deal!

The teacher made sure the student knew this. “Where did you learn about ellipses? We haven’t even taught that yet?!” Her voice was a mixture of curiosity and enthusiasm. “I bet you saw an ellipse in a book. Do you remember which one it might be?”

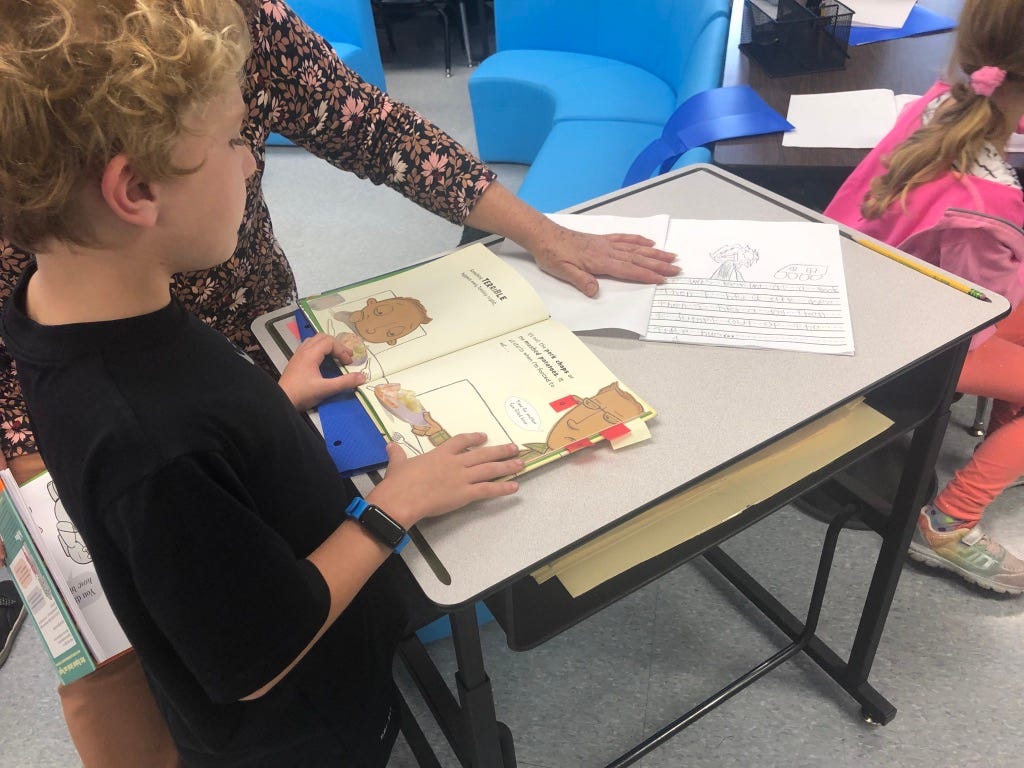

Thinking for a moment, the student went and found a book in which he might have found the ellipse. Not locating it, I opened up the picture book at his desk and pointed toward a page. “Is that it?” I asked. “Yes!” the teacher exclaimed, and then spoke to the student directly: “Can we reread this page to learn what ellipses do?”

As he read the text, his voice trailed off when he reached the ellipse. “You read that correctly!” The teacher went on to share that ellipses must tell the reader that something important is coming up on the next page. “It’s the same way you used it in your writing.” The reading-writing connection was made clear.

Clearly, the teacher understood her students and what was expected of them in 1st grade. This learning experience is more likely to stay with the student vs. a grammar worksheet on ellipses. The assessment was in context and authentic. What made it effective was the quality of the timing and the teaching.

Formal Conference with a 5th Grade Reader

I am always willing to try whatever strategy the teachers are attempting to embed in their practice. Recently, a 5th-grade teacher asked me to model a reading conference. After reviewing current literature and finding a conferring template (“It’s been a while since I have done one of these,” I confided to the teacher.), I felt ready enough.

The first video depicts my conversation with a reader before she spends a couple of minutes reading the book she selected for independent reading time.

The second video is of our conversation about what she read, what I thought she was doing well, and a few teaching points to consider for the future.

As teachers, we learn so much about our students when we have real conversations. In this one instance I discovered the following:

The student is a courageous reader, willing to take risks in new genres. This likely means she is also a confident reader. She can apply strategies learned and is also open to new ones.

The classroom library is diverse and has high-interest texts.

The teacher is providing students with adequate time to read independently (the student was almost done with her book).

We live in a culture that values outcomes over process. If we don’t have something to show for our work, did we accomplish anything? Yet getting things done has a cost, such as often missing much of the journey we took to arrive at success. Conferring with readers and writers is a process that is also the outcome. So much can be learned if we are willing and able to pay attention to what is shared.

References

Ackerman, K., & McDonough, J. (2016). Conferring with Young Writers: What to Do When You Don't Know What to Do. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Routman, R. (2018). Literacy Essentials: Engagement, Excellence, and Equity for ALL Learners. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

For the month of October, premium content is free for everyone. Continue to access all publications starting in November by subscribing below.