Expertise Matters #engaginglitminds

As I read Engaging Literate Minds, a central theme that keeps replaying in my mind is simply, “Expertise Matters.” Every teaching move, every dialogic conversation, every piece related to data, literally everything that is shared on the pages of this book is based on teacher expertise, including the onus on the part of the teachers to seek out their own professional learning through collaboration with their colleagues.

One example of onus on our own learning was evident in Chapter 12. The students and their teacher, Merry, were frustrated with Spike for his perceived non-participation in the group discussion. When Kathy invited the group to reenact the discussion, everyone came away from the experience with a new understanding and appreciation of the dynamics of productive collaboration. It behooves us to value how much we need each other to keep ourselves engaged in the most productive practices.

When looking at assessments, especially informal assessments, expertise is the cornerstone. If there are gaps in the teacher’s understanding of what is developmentally appropriate, or if the teacher doesn’t have a strong grasp on phonemic awareness, phonics, and how to identify children’s approximations when writing, then the data is for naught. It helps no one.

Assessments should be as much for the teacher to identify their own gaps as it is for them to assess the learning gaps of the student. For example, if little Johnny isn’t catching on to foundational reading skills, what do I, the teacher, need to learn and do in order to help him?

The following quote was in reference to required testing,

“...They are used for communicating with others about the child’s general work knowledge development. It is the details of the separate areas of development, not the categories, that allow Sarah to focus her instruction.”

- p. 231

The communication piece in relation to the child’s “general work knowledge” is problematic for me. I see this all too often in IEP meetings, collaboration meetings, and conferences with parents. Data points are discussed. Data, not children or their approximations, not their individual learning accomplishments, not their contributions to the classroom community, and certainly not their interests. The problem with this, in my humble opinion, is that when we only look at the numbers, we can become distracted from recognizing the child as a full human being. It stems from a deficit mindset, indicating that the child is the problem. I assure you, the child is not the problem. We must do better.

Sarah relies on the details of the separate areas of development, not the categories in order to deliver a responsive curriculum to each one of her students. And I love this...

“As Sarah learned more about the complex nature of emergent literacy acquisition, she realized that she needed more than just numbers to get a complete picture of her students as readers and writers.”

- p. 231

She needed MORE than just numbers to get a complete picture. Literacy is complex! The beauty that resonates here allows for the comprehensive, responsive nature that is clearly embedded in Sarah’s teaching. It is evident upon further reading that Laurie and Andrea follow suit, using all their data collection and organizing to notice, to wonder, and to be responsive to their students.

Informal assessments are windows into a child’s thinking. This makes sense when reflecting that the origin of the word “assessment” comes from the Latin root assidere, which literally means to sit beside. Now, consider what could be if we shifted the conversation to highlight the whole child, and then had conversations that pinpoint instructional moves based on the assessment of the whole child.

Chapter 14 talked about the data tracking system for three different classrooms. Although each teacher had a different system of organization, they had certain things in common:

All three are process oriented

All used multiple types of assessment to get a more complete look at each student (informal classroom observations, anecdotal notes, anchor charts, formative assessments)

All the data showed change over time

All three were positive and used approximations as a place to develop growth mindset

My point is, it’s less about your data tracking and organization thereof, and more about how that data helps you become more comprehensive and therefore more responsive in your teaching.

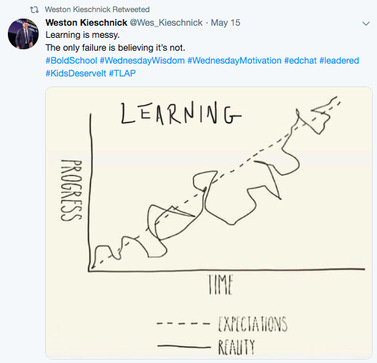

Knowing and understanding children’s development and the intricate complexities of literacy is paramount. And...one must know and understand that learning is not a straight line.

I think this image created by Weston Kieschnick, sums up what the authors of Engaging Literate Minds were thinking on p. 247 when they stated, “It is not unusual for students to look as though they are going backward before they move forward.” If we don’t have this understanding, we might assume that kids aren’t learning when their data point slips on one assessment or another. More than likely, they are just on the cusp of learning something new...

After reading and reflecting, I’ve developed a few ideas for what continuing to build expertise in my district might look like…

Collaborative meetings with colleagues where we look at actual student writing, notice approximations and what the child can do, and then work together to plan instructional moves.

Videotaping lessons and reviewing the lessons with a trusted colleague; planning instructional moves based on the review and our conversations.

Engaging in a book study to further develop expertise (and offering choice to teachers on what book they feel would best meet their own learning needs).

Examining different ways of collecting data, organizing data, and then planning instructional moves based off the data.

Taking turns observing in a peers classroom and then following up with discussion and planning of next instructional moves.

Sharing my template for IEP meetings with my colleagues (it helps me to focus on the whole child during the meeting, as opposed to just talking about data) --> IEP doc

At some point teachers need to differentiate their own professional learning through collaborative efforts with their colleagues as well as through professional organizations where opportunities to grow in expertise exist. Just like students need differentiated instruction, teachers need differentiated professional learning, and as good as any one district is at professional development, it is unlikely that they are able to provide everything one needs to be an expert teacher. The onus is on us. It has to be.