What conditions can instructional leaders cultivate to create more open and trusting cultures? How can leaders help teachers feel that their interactions with each other are value-added vs. evaluative experiences? This post continues this conversation started last week (here).

Condition #1: Always let the teacher know what you observed and what you thought.

When visiting classrooms, don’t leave without handing the teacher some affirming notes and/or having a cordial conversation about instruction. Teaching is a highly personal practice. Not knowing what the boss thinks about their instruction can leave a teacher assuming the worst. This can affect their identity as a teacher, leading them to question their practices and beliefs.

My notes were pretty simple: a blank sheet of paper with three things: 1) my observations, including what students were saying and doing, 2) a mix of positive commentary and genuine questions related to what was observed, and 3) a short summary of my experience, including a final question to guide them to reflect on their practice in a constructive way.

Condition #2: Ensure that professional development is in place and of high quality.

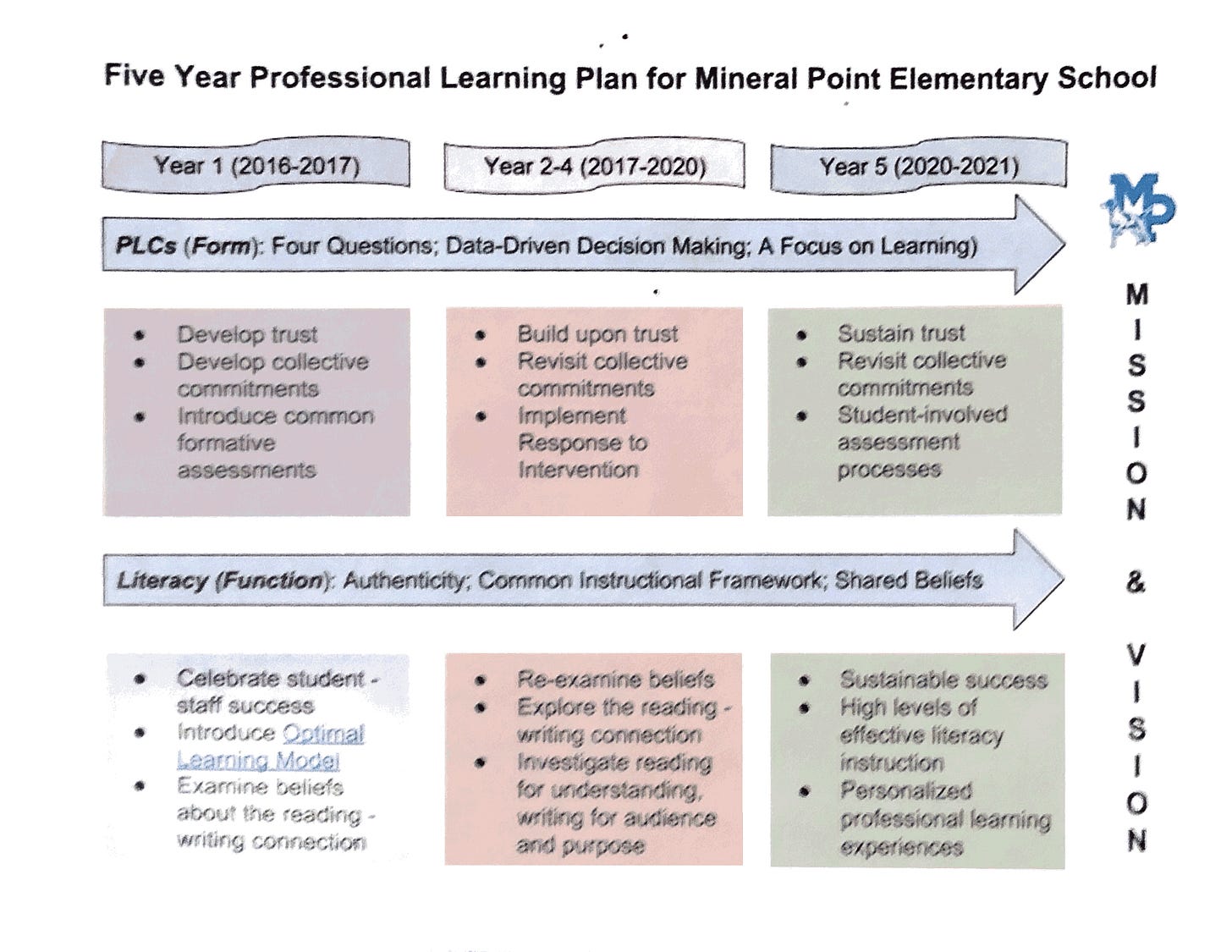

One reason schools aren’t improving is the lack of new ideas coming into the organization. It’s difficult to get better purely through observation and feedback. My instructional walks were less effective when our professional development wasn’t focused or we weren’t getting together regularly to learn together.

One of the best approaches for professional development is for the entire school to grow in general instructional practices, for example assessment or differentiation. These elements of teaching are universal; the physical education teacher, the interventionist, and the general classroom teacher can all try and apply the same skills. They can be embedded in content-specific PD such as literacy. At the same time, ensuring general instructional practices are the focus makes it easier for leaders to engage in coaching conversations that are both personal and consistent.

Condition #3: Clarify what effective instruction looks and sounds like.

I learned as a principal that leadership cannot be clear enough about effective instruction. It’s one thing to read professional literature, discuss promising practices with colleagues, and watch it in action via video or live demonstration. It’s another thing to expect these practices are applied with integrity in classrooms.

Educators see and understand new ideas through the lens of their current beliefs and biases. This translates to variations in implementation. I never expected nor wanted each and every classroom to look and operate exactly the same. And yet I did expect that we were all trying and applying new strategies with some level of consistency.

When I observed discrepancies between classrooms during instructional walks, that was a sign that we needed to dive deeper into a strategy or concept. For example, when we learned about co-organizing classroom libraries with students, a few teachers struggled. In response, we spent time finding consensus around collective commitments related to classroom libraries.

Some teachers struggled to give up control. That was the point of the PD - to empower students as readers and to teach with greater simplicity. By sharing this schoolwide data, we could have a conversation about what obstacles teachers were feeling and how to respond.

Condition #4: Focus on asking good questions vs. giving advice.

I’ve learned over time that my initial assumptions about where teachers need to grow are as likely wrong as they are right. I likely haven’t taught at their grade level or in their subject area as long as they have. Even if I had, I’ve been “out of the game” long enough to recognize my limited knowledge.

That gives me a good excuse to generally not give advice. What I leaned on as a leader is a) an instructional framework that describes the most promising general practices, and b) asking good questions.

A good question in the context of being present in classrooms is one that leads to a teacher to discover an insight into their current practice. This question isn’t necessarily introducing a new idea. It helps a teacher connect the dots between what they are already doing and what’s possible.

For example, I was in a middle school ELA classroom this school year. The teacher had posted students’ anonymous six word memoirs on the wall. They were thoughtful, reflective stories that also worked as poetry: “Still figuring out who I am” and “You don’t know what it’s like”. I told the teacher that this wirting is very 6th grade. “Oh, yes”, she agreed, laughing.

We had also talked about increasing the amount of usage of her classroom library. In particular, we discussed how many classroom libraries lack enough low readability, high interest texts for up-and-coming readers. Thinking about the memoirs some more, I asked her how student writing might serve to address this need. She thought for a few moments. “Ooh, I never considered that.” This question led to brainstorming ways to organize students’ writing into bounded texts, starting with the memoirs. “They could be a resource to help my new students transition into sixth grade next fall, to get a glimpse of life in middle school.” Although I had taught 6th grade previously, it was my participation in high-quality literacy professional learning with teachers that had built up my knowledge about the reading-writing connection.

Conclusion

If the only time a principal is in classrooms is for formal observations and teacher evaluation, could you say they were ever truly present? One could argue that this is a type of absence. While physically in the classroom, they are only observing a tiny sliver of the teaching and learning experience. Principals are as biased as anyone else. They see through the lens of their own beliefs about what good instruction is and is not.

School leaders being present in classrooms through instructional walks is part of a healthy accountability system for everyone, not just teachers.

Leaders ensure teachers feel seen and supported through leaving notes and engaging in conversation during regular, informal visits.

Leaders participate in high quality professional learning with teachers to help everyone get on the same page regarding effective instruction.

Leaders continuously clarify the elements of promising practices with teachers (and not simply to teachers) to ensure greater coherence across the school.

Leaders communicate feedback through thoughtful questions that lead to insight vs. giving advice that may not be accurate or what teachers need.

When leaders are present in classrooms, everyone gets better together.