If you have a few minutes, it would mean a lot to me if you could complete this survey. Your feedback will help me improve this space and my pratice in general.

Do you still believe what you believed when you first started out as an educator?

If your answer is “no”, what was the process you went through to change your mind?

The first question was likely easy for you in which to respond. For instance, I recall believing that if I taught a literacy curriculum program with fidelity, all of my students would become successful readers and writers.

However, the second question is more difficult. We rarely pause in our work and examine our own thinking. This seems especially true when it comes to our beliefs about literacy instruction.

We should notice when our beliefs change. They drive our decisions about how to teach, how to lead, how to coach. If factors that we don’t want influencing our beliefs become entrenched without our awarness, this impacts our students.

As an example, commercially-produced curriculum resources are one of the biggest influencers of our beliefs and practices. Teachers are expected to commiting to using these programs. There is sometimes the expressed belief that they alone will unlock our kids’ capacities as readers, writers, speakers, thinkers. So we teach the lessons with fidelity.

But what about the learners? Is today’s lesson what they need…today? How do we know, and what do we do if we discovered that the answer is “no”? If we become too reliant on a resource, we lose our capacity to call upon our craft to meet our students’ needs. We don’t know what we know or believe.

To counter this overreliance on outside factors influencing our beliefs, I offer the following four questions to regularly examine them. You can respond to these on an annual basis, or whenever you feel lost or unsure about literacy instruction.

Question 1: What do I believe about literacy instruction?

Write down your core beliefs about literacy instruction. For example, think about the instructional models you use, such as the gradual release of responsibility. Consider what you prioritize in your teaching—be it decoding skills, comprehension, or student engagement.

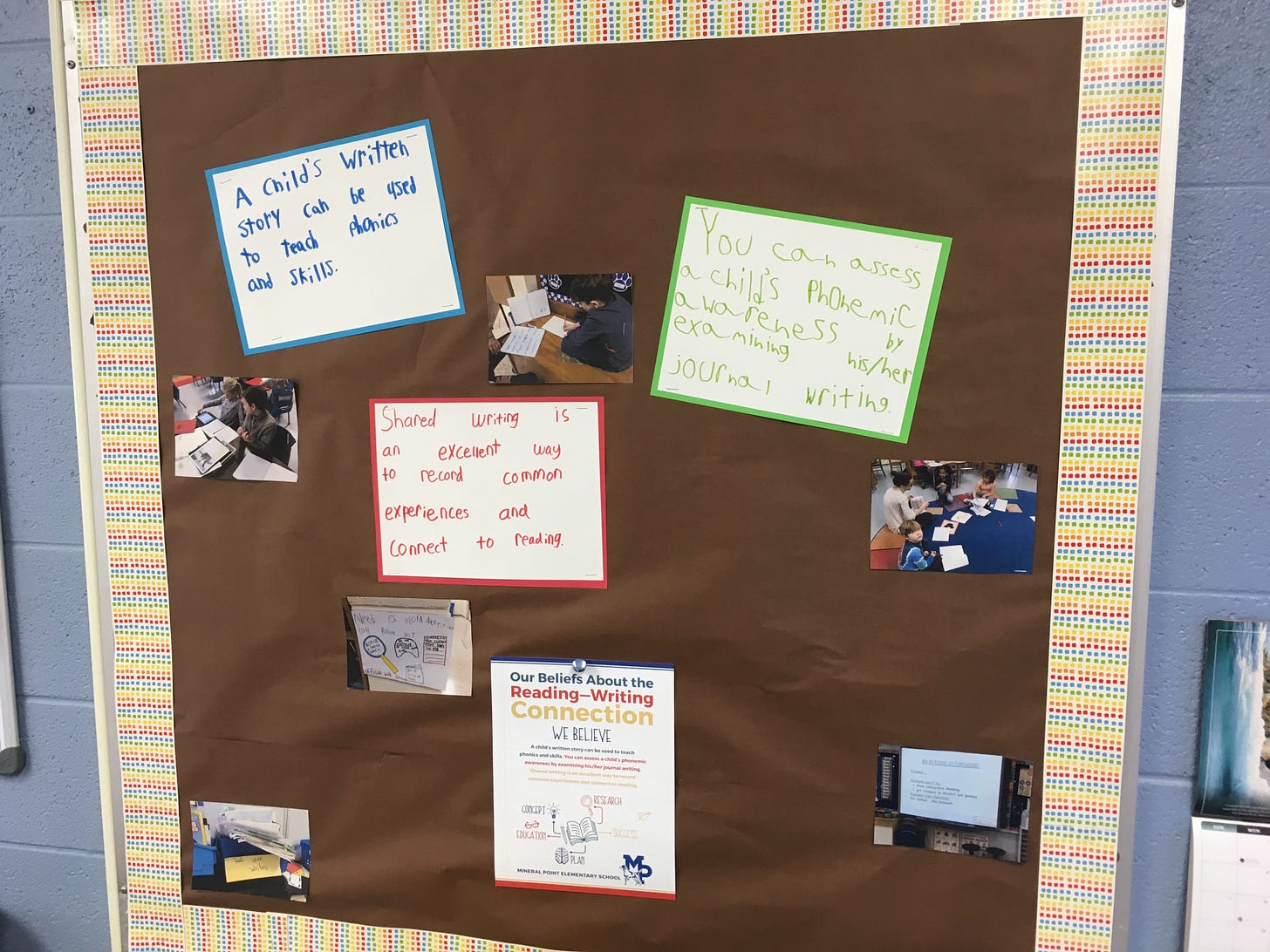

Below are the first set of beliefs my last school came to agreement upon initially as a faculty.

Question 2: Why do I believe what I currently believe?

Trace back to the roots of your beliefs, such as:

How you were taught in school

Impactful literacy courses during college

A mentor during your early teaching years

Witnessing successes and failures in different instructional settings.

Write out personal anecdotes to connect deeper with your educational philosophies.

Question 3: What if what I believed was wrong?

Really imagine this situation. How would you feel if you were told by someone you respected that how you curently teach is ineffective?

For example, what if “a child’s written story could not be used to teach phonics and skills”? What would the argument be against that? Maybe a colleague would cite the lack of time to prepare an activity like this. Maybe they prefer workbooks.

The purpose of this exercise is not to actually change your mind. It’s to exercise your capacity to engage in critical thinking, to not hold any belief too tightly. Other professionals, for example lawyers and scientists, regularly interrogate their current positions. You will look at your belief more objectively. It also connects with the final question…

Question 4: What do I need to be convinced that my current beliefs are right?

Specify what evidence or data would be needed to support your current set of literacy beliefs. This could involve new research findings, observing a colleague successfully implement the beliefs in action, or gains in your students’ engagement and outcomes from your practices.

A Succinct Summary and Closing

Here are the four questions for examining your literacy beliefs:

What do I believe about literacy instruction?

Why do I believe what I currently believe?

What if what I believed was wrong?

What do I need to be convinced that my current beliefs are right?

As you engage in conversations with colleagues around your beliefs and practices, approach them with empathy. Focus on shared goals rather than differences. Emphasize the importance of dialogue in fostering professional growth and improving literacy instruction collectively.

The value of questioning and reassessing our beliefs is a path to professional growth and better educational outcomes.

How do you examine your current literacy beliefs? What do you believe to be true?

Related Recommended Reading

These four questions are adapted from an article I wrote for Choice Literacy, “Examining (and Changing) Our Literacy Beliefs over Time”. I shared a longer example, of how two teachers’ collaboration around a student in intervention changed my belief that a curriculum resource could not be effective for supporting all students.

- provides a powerful rebuttal to teaching phonics in isolation, and the SoR movement in general, in this article. He cites comments from researchers such as Mark Seidenberg to counter these unsupported beliefs.

Likewise, John Warner questions the “science of writing” in this article, noting that the use of “science” with anything may be more of a marketing term than based on actual science.

Did you find this post useful? Subscribe today if you haven’t already, and let a colleague know about what you are learning.