Honesty in Uncertain Times

Article

Teachers want answers and I too often don’t have them. Not only are we dealing with a pandemic like everyone else, but we are also starting a ~12 million dollar renovation project for our school.

Given these circumstances, I’ve been careful to not put too much on faculty. For example, we have not pushed new learning. “We’re lucky we went to remote learning in the spring,” I’ve commented. We have sustained our efforts and supported student independence.

But reluctance to commit to anything beyond the status quo for too long can lead to a limiting of our beliefs. We can become blind to what’s possible in these circumstances. So I’ve started planting the seed of shifting to new learning this spring. “Try something out,” I’ve shared, such as shared writing of poetry in a Zoom session.

How do we as leaders make this shift, balancing compassion with a sense of urgency? The rest of this article offers three benefits of honesty and how to adapt this quality with uncertainty.

Honesty Fosters Trust

One thing made clear during the pandemic is that we are reliant on each other in order to be successful. This means trust is essential if we are to collectively engage in this work. We can only trust someone if we believe what they say and do is from a place of authenticity.

Megan Tcshannen-Moran relays this reality in her book Trust Matters: Leadership for Successful Schools (Jossey-Bass, 2014, p. 20):

Trust matters most in situations of interdependence, in which the interest of one party cannot be achieved without reliance on another. Interdependence brings with it vulnerability.

The author highlights honesty as one of the five facets of trust and describes it in further detail (pg. 25-26):

Honesty concerns a person’s character, integrity, and authenticity. When you trust someone, you believe that the statements he or she makes are truthful and confrom to “what really happened.” You are confident that you can rely on the promise of that individual, whether verbal or written, and that this individual will keep commitments made about future actions.

In other words, an assessment of honesty involves a person’s ability to follow through and to be forthright when they cannot. Thinking about everyone trying to learn, teach and lead from a distance, we have little choice but to trust that others will keep their commitments.

Honesty Increases Confidence

Being honest is not the same as “saying it like it is.” Leaders employ reason to ensure that the message is not being mixed up with the social and emotional factors that might skew understanding. When we allow our unfiltered thoughts to be expressed, we risk decreasing someone’s confidence in themselves. This is venting, not honesty.

Real honesty should build someone up. It first acknowledges that we do not have all the answers, or as others think we might. It allows for the person to talk and express their ideas without worry of judgment. This is facilitated by expert listening.

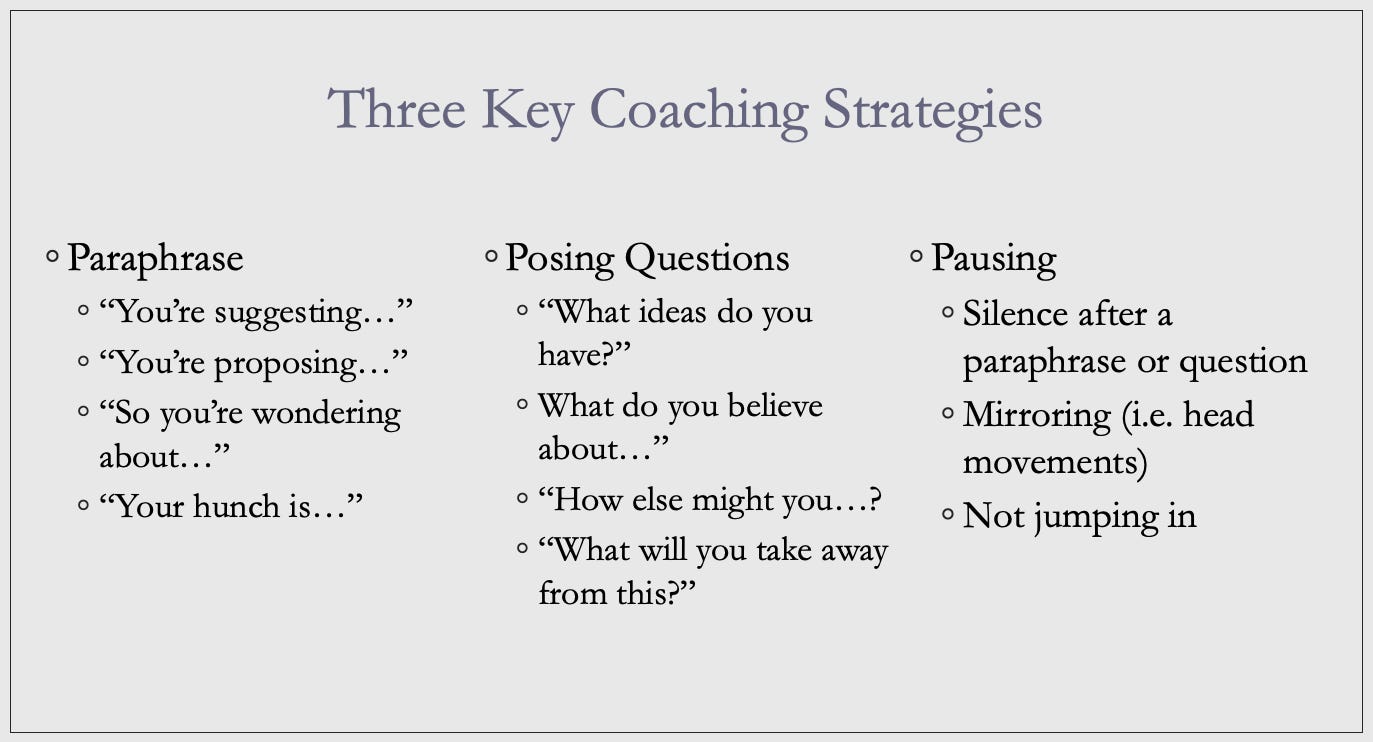

In their book Cognitive Capital: Investing in Teacher Quality (Teachers College Press, 2014), Arthur Costa, Robert Garmston, and Diane Zimmerman offer a mental map for leaders and coaches to improve their listening skills in order to reach clarity about an issue. Three key listening strategies include paraphrasing, pausing, and posing questions. Next are some sentence/question stems that might be helpful.

When we engage in conversation with the intent to understand, we can give up the role of expert; so honest in uncertain times. It’s also respectful of the other party’s capacity to develop solutions to their professional challenges and responsibilities.

Honesty Grounds Us

“Uncertain times” already feels like a cliché even though the pandemic is only months old. Yet some feeling of uncertainty has always been with us, part of our experience in not being able to control or predict the future. Is it helpful to simply dismiss it?

By saying, “I don’t know,” or “I’ll get back to you on that,” we acknowledge our own uncertainty. We can also ask others for their thoughts first on an issue before sharing our own current position.

Nelson Mandela led in this manner. Referring to it as “leading from behind,” he would have advisors first voice their ideas during a discussion. This increased the likelihood of a better decision as all ideas were available and uninfluenced by the leader’s current position. It also creates a sense of share leadership and purpose, something less likely with the leader alone making decisions.

As this Harvard Business Review article highlights about the concept:

People are looking for more meaning and purpose in their work lives. They want and increasingly expect to be valued for who they are and to be able to contribute to something larger than themselves. People expect to have the opportunity to co-author their organization’s purpose. They want to be associated with organizations that serve as positive forces in the world.

In short, being honest about our limitations gives space for others to lead.

Short Summary: How to Be Honest in Uncertain Times

Follow through on your commitments.

Ask for help when a task is beyond your individual capacity.

Become an expert in listening.

Lead like a coach by paraphrasing, pausing, and posing questions.

Publicly acknowledge your own uncertainty.

Ask others to contribute their ideas before sharing your own.

Create space for others to lead.