How Can Principals Support Effective Literacy Instruction?

When walking through our school’s classrooms, I often see students independently engaged in reading and writing. Yet I am still surprised when a teacher says, “Gosh, sorry you came at this time. We were just doing some independent work. Maybe come back later when I am teaching?” In my first year as a principal, I would politely oblige and go to another classroom. Now, I smile and say, "Of course you are! What else would you be doing?”

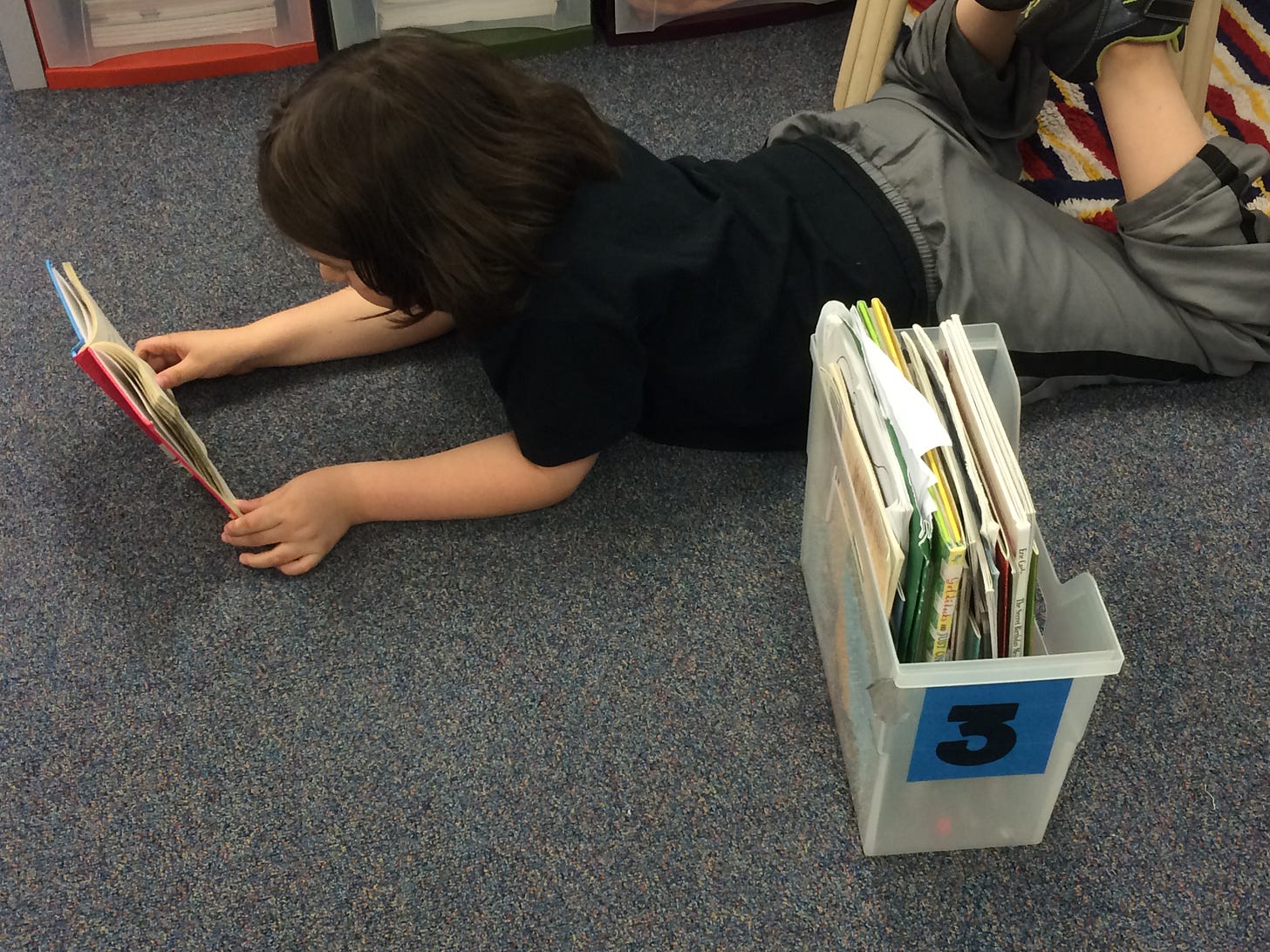

When we give students time to practice the skills we have explicitly taught them, it is only then that we allow them to become readers and writers. Teachers need to stop apologizing for taking a step back and allowing our kids to walk on their own path toward proficiency. Guiding students to become independent, lifelong learners should be the ultimate goal in any classroom. The Daily 5 framework (Boushey and Moser, 2014) gives structure and purpose when striving for this laudable goal.

Highlighting Dr. Richard Allington's 2002 article "The Six Ts of Effective Elementary Literacy Instruction", here are three practices that can move kids forward: Time to read, lots of texts that are readable and interesting, and a teacher who knows his or her students and understands literacy. Principals are essential in supporting these practices in school.

1. Time

Principals can create time for teachers through thoughtful scheduling. One of our priorities when creating the school schedule is blocking off at least 90 minutes for literacy, and two hours in the primary grades. Then we hold that time sacred. Announcements are kept to a minimum. We do our best to ensure that intervention support takes place beyond that block. Less effective practices, such as worksheets and test prep, should not have a place during this time.

Reading and writing also shouldn’t occur exclusively during this time. For instance, principals can encourage and expect teachers to integrate reading and writing within the content areas. This year, grade level teams in our school projected out integrated units of study (Glover & Berry, 2012). Students, especially English Language Learners and those with learning disabilities, benefit from seeing science, social studies, and literacy connect with each other in meaningful ways. Content integration is also a big time saver.

2. Texts

Notice the use of the word “texts” and not “books”. Principals should consider comic books and graphic novels, eBooks, and magazines as worthy purchases. They can pique the interests of our most reluctant readers, especially boys. Rethinking what a text looks like can make all the difference for engaging students in reading.

The best placement of texts is in a classroom library. In our school, we always try to devote a significant portion of our budget to this area. Teachers are given latitude in what titles to purchase for their classrooms. That’s important, because they know their readers’ interests and skills better than anyone. Through this investment, we have observed a high percentage of texts students carry come from classroom libraries. If there is a lack of funds, we consider other options, such as the school’s PTO, community organizations, and central office.

3. Teach

Whenever we interview candidates for a teaching position, one question I always ask is, “What have you read lately?” If they struggle to come up with a title or two, it is fair to say they may not see reading as a lifelong endeavor. But to be an expert reading teacher, educators have to be more than just familiar with children’s literature. Quality instruction should include clear modeling, shared demonstration, guided instruction, and time to practice these skills independently (Routman, 2014).

Showing teachers how to embed ongoing assessment throughout instruction can happen a couple of ways. For example, principals can bring in literacy experts to demonstrate these skills. If this is cost prohibitive, consider online professional development services, where teachers can view best practice in action. Also, time can be provided for teachers to collaborate about what works and share these findings. For instance, my second grade team held discussions about their understanding of the Daily 5 and the CAFE framework (Boushey & Moser, 2009). These visible conversations can elevate the professional discourse throughout the whole school. The subsequent impact on shared beliefs and student learning can be profound.

Within the Daily Five framework are mini-lessons. These brief teaching points are critical toward building independent readers and writers. Without this explicit instruction in between these times to practice, students lack the appropriate modeling, purpose and guidance for their work. Just like in sports, players need an effective coach so they can practice both what they know how to do and stretch themselves to attain new skills.

Is It That Simple?

Well, certainly not the complex practice of classroom instruction. But what we should provide during our instruction is pretty straightforward: time to practice, texts that are interesting and readable, and great teaching.

References

Allington, R. L. (2002). "The Six Ts of Effective Elementary Literacy Instruction." Retrieved from http://www.readingrockets.org/article/96 on April 20, 2014.

Boushey, G. & J. Moser (2009). The CAFE Book: Engaging All Students in Daily Literacy Assessment and Instruction. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Boushey, G. & J. Moser (2014). The Daily Five, Second Edition: Fostering Literacy Independence in the Elementary Grades. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Glover, M. and M. A. Berry (2012). Projecting Possibilities for Writers: The How, What, and Why of Designing Units of Study, K-5. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Routman, R. (2014). Read, Write, Lead: Breakthrough Strategies for Schoolwide Literacy Success. Alexandria, VA: ASCD

Post a comment and possibly win a copy of The Daily 5, Second Edition. Check out the rest of the posts in this week's Stenhouse Daily 5 Blogstitute:

May 5: Ruminate and Invigorate by Laura Komos

May 6: Enjoy and Embrace Learning by Mandy Robek

May 8: Read, Write, and Reflect by Katherine Sokolowski