How to Effectively Communicate a New Literacy Initiative Process

Including a premium guide for full subscribers

Thanks for reading! Subscribe below to receive all posts. If you are looking for more support at the end of this article, I offer a course on making classroom visits a habit, as well as coaching for leaders and leadership teams. Take care, - Matt

“Not in his goals but in his transitions man is great.”

—Ralph Waldo Emerson

Managing schoolwide change was one of the most challenging tasks of my time as a principal. Some staff were comfortable with the status quo, while others felt a change should have been made the previous year. Regardless of the choice, some championed it while others questioned it.

And when the decision involved literacy, the dial turned up on the celebrations and critiques.

What I have learned over time is, while a decision that impacts the whole school will always bring some stress and resistance with it, the experience can actually be rewarding. The key is to have an effective plan for communicating the initiative throughout the entire change process.

The next recommendations are a mix of actions I did well and some moves I wish I would have made.

#1 - Acknowledge the loss

The why of any literacy change (usually a curriculum acquisition) consists of two drivers: the belief that the current resource isn’t meeting students' needs and the hope that a new one will.

This can create the perception that the old curriculum never worked in the first place. This may make some teachers who were part of that previous acquisition process feel disrespected. At the time, it looked like a good decision. Maybe it even did have some positive impact on students.

Acknowledging the loss and letting go of a previous initiative shows respect for the work that went into it. You might have a “service” for the outgoing curriculum resource. “Would anyone like to say a few words?” you can ask at a staff meeting, with a copy of the teacher edition at the front. Done with respect and some light-heartedness, acknowledging what a school culture is losing can provide some closure as you make room for something new.

#2 - Introduce the new language

In my work as a systems coach, my colleagues and I like to point out to clients that what we call things matters. Words have power. Language both illuminates and constrains. To spread promising literacy practices, a faculty has to be on the same page about what each practice entails and how it can be most effectively implemented in classrooms.

For example, at my last school we differentiated “shared writing” from “interactive writing”. We clarified that shared writing is when the teacher is holding the proverbial pen while they and the students draft something together. It was also our preferred practice; interactive writing, with the students writing in front of the class, was too cumbersome and inefficient. When I would go into classrooms as we tried out this practice, I would reinforce the terminology in my feedback for and conversations with teachers.

#3 - Be transparent, open, and inclusive throughout the process

While it would be easier in the short term to just make a decision about a literacy initiative at the leadership level, the long term results are usually met with lots of resistance. It’s better and more respectful to invite all staff to offer input and participate at some level in the process.

Simple things to do include:

Post agendas for meetings in advance.

Share minutes promptly afterward.

Collect feedback throughout the process.

Additionally, institute norms and agreements for how everyone is to conduct themselves if discussions and requests for feedback occur in real time such as at staff meetings. Nominate a process checker, a timekeeper, and a note catcher to ensure accountability of what is said and not let the meeting go too long.

Finally, clarify the decision making process. For example, when my last school explored a new curriculum resource, we made it clear that the instructional leadership team would make the final recommendation to the school board. This team included several teacher leaders. We listened to everyone’s feedback, but only a handful of teachers had decision-making authority.

Criticism doesn’t have to be negative. In fact, it can be your friend if it allows everyone’s voice to be heard now rather than after implementation of the new initiative has started.

#4 - Empower teachers as leaders

A question I have asked of principals who seemed overwhelmed is: Are you doing something that someone else is better at?

Steering the ship alone, especially for big projects, almost always led to missed deadlines and disappointed colleagues. When I empowered teachers as leaders, and especially when I put them in positions that suited their strengths, I always looked better.

For example, I asked our instructional coach to set up the webinars with curriculum publishers. She also set up site visits at other schools to preview resources in action. This freed me up to be in classrooms more and interact with faculty, including answering questions about the process. Plus, no missed deadlines.

#5 - Share progress toward goals

As the saying goes, nothing succeeds like success. But visible progress can be tough to see when you are working in the knowledge profession.

One way to make progress toward goals clear is to create a visual roadmap. There is a clear starting point, benchmarks to achieve, and some type of finish line. It doesn’t have to be a strict pathway; feel free to give yourself permission to chart a different course than planned if needed.

As an example, the big project I work on is exploring a roadmap for schools that engage in building their multi-tiered systems of supports. There are a lot of steps and waypoints. I think this speaks to the complexity of the work, which hopefully communicates with leadership teams the type of commitment needed long term.

Each initiative is unique. For instance, the roadmap for a literacy curriculum acquisition wouldn’t end when a decision is made regarding the resource selected. Implementation stages would include time for professional development and data analysis through an equity lens. Communicating progress can occur regularly through school newsletters and at staff and district meetings.

#6 - Replicate the process and sustain the work

At the end of my last book, I asked the reader: What will be your legacy? My message of hope is that a school operates effectively without your physical presence. I think that’s the true test of one’s leadership.

One way to do that is to examine what worked from a previously successful initiative. Then think about how you can replicate and adapt the principles of that process for another schoolwide change.

Equally important is to sustain the changes already made. The loss of leadership without institutionalizing the practices and beliefs that support schoolwide change can be tragic.

Leaders can “concretize” the change by developing a handbook and related materials that clearly articulate the process, history, and commitment made to the work. Make sure the resource gets in the hands of all shareholders.

While these six recommendations aren’t the only steps to take when communicating a new literacy initiative, they stand out to me as the key factors that made the difference between a successful and an unsuccessful change experience.

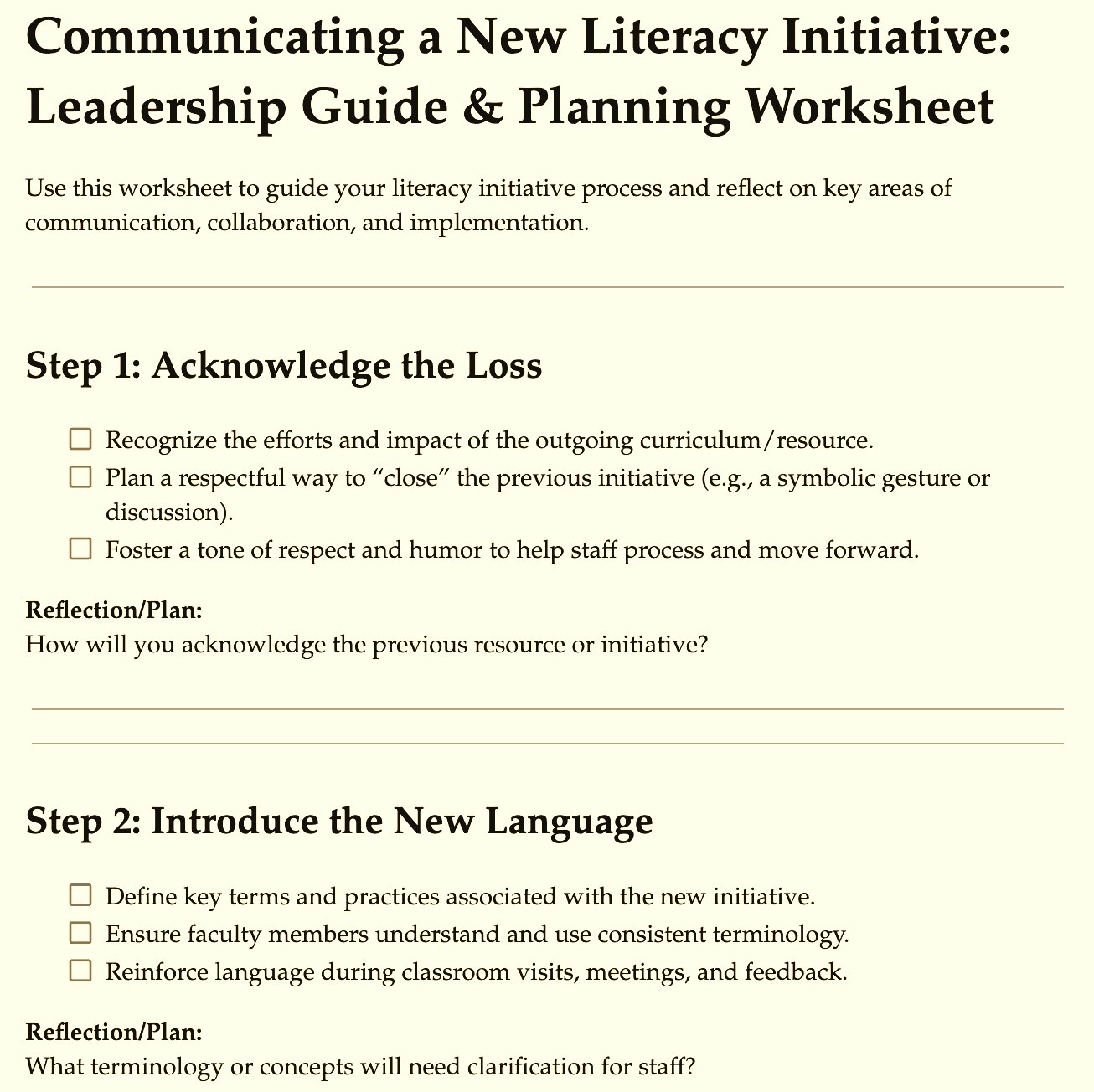

For full subscribers: Download this post’s companion communication guide and planning document below.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Read by Example to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.