Instructional Walks: From Judging to Learning

Article

“How am I doing?” It’s a consistent question at the top of teachers’ minds. Whether in the midst of daily instruction or reflecting on one’s practice over time, educators want to know if their daily work with students is making a positive impact on their kids’ literacy and academic engagement, achievement, and enjoyment.

As a former classroom teacher, I can attest to this constant (and often critical) inquiry. The negative narrative can be hard to turn off. It’s also the question that administrators desire to answer during classroom visits. If you too have this wondering on your mind, then we have found common ground.

Of course, the answer is not simple. Teaching is too complex. Efforts to document and evaluate faculty have struggled to capture the complexity of instruction. Checklists and rubrics reduce instruction into its basic elements, like the ingredients in a recipe. But teaching and learning are more than the sum of its parts. It is a thinking and doing process and craft unlike anything else. Current tools are not enough for understanding instructional effectiveness, to answer the question, “How am I doing?”.

As I think about it, what if this question is the wrong one to ask? Do we really need to judge everything we do in schools? What if the majority of our time together was spent appreciating what we were doing and adopt a curious stance toward the outcomes? With this inquiry in mind, I suggest a strategy that takes a more learning-centered approach when visiting classrooms as leaders: instructional walks.

My Judging-to-Learning Journey

I encountered this leadership strategy in my first school as an elementary principal. Regie Routman, author of Read, Write, Lead: Breakthrough Strategies for Schoolwide Literacy Success, spoke at a literacy leadership institute. She coined the term “Instructional Walk” and defines it as:

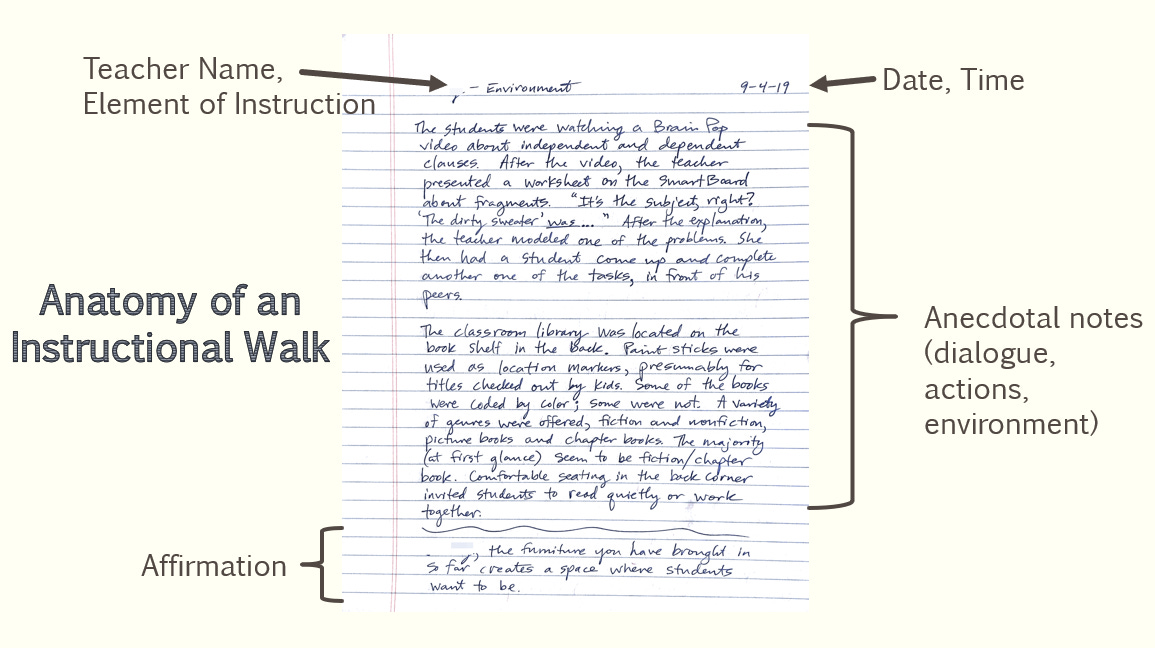

“an intentional, informal visit (not an evaluation) by the principal to a teacher’s classroom to notice, record, and affirm strengths, build trust, offer possible suggestions, or coach – all for the purpose of increasing student literacy and learning across the curriculum” (306).

The image below is an example of one walk from this school year. I write a page-long narrative of the instruction observed, noting and naming what’s going well.

Teachers have repeatedly commented on how much they appreciate the affirmation and constructive feedback about their work. It’s low stakes and highly collegial.

Yet coming back to my school after the institute in 2012, I was initially skeptical. Quietly, I raised several questions and concerns to myself:

I already do teacher observations – isn’t this redundant?

I don’t have enough time in the day for one more thing.

Teachers will feel uncomfortable with me popping in their classrooms unannounced.

So I put instructional walks on the backburner as I continued on as principal. Now, seven years later, I am engaged daily in instructional walks, devoting at least one hour to visiting classrooms and experiencing instruction. What changed? And why did the change that occurred take so long?

To start, I realized after more time in classrooms how ineffective the teacher evaluation process by itself is for facilitating professional growth. I do see the merits of this system of standards for addressing poor performance. Also, specific indicators of practice under common domains such as “Instructional Delivery” and “Assessment Of and For Learning” provide much-needed clarity and a sense of objectivity when principals observe teachers.

In addition, a standards-centric evaluation process is an improvement on previous systems, such as when a supervisor would pop in and write only a qualitative narrative of instruction through their subjective point of view. But both processes are evaluative in nature. We are making a judgment, professional as it may be, about a complex experience. If the information collected from an observation is used to make decisions about one’s performance or their employment status, how can it promote growth?

This realization about the limits of formal evaluation reminded me of my own experiences as a classroom teacher with an ineffective evaluation system. Specifically, I recall two observations from former principals.

During my first year as a 6th-grade science teacher, the principal came in for an announced formal observation. We were studying molecules by growing crystals using charcoal and common household chemicals. When trying to demonstrate how to break up the charcoal briquettes for the students, I discovered that I couldn’t do it without a significant swing of a hammer. Subsequently, the lesson was not completed by the proposed time because I had to personally break the briquettes for each student pair. After the lesson, the feedback I received from my principal was to “always have a Plan B for science labs and for lessons involving technology”.

In another school as a 5th- and 6th-grade classroom teacher, I was leading a guided reading group. The focus of the lesson was to identify parts of speech while reading a social studies trade book. My principal stopped in for an unannounced visit. After hanging around for a few minutes and observing what everyone was doing, he left. Later I found a note in my mailbox. “I liked that lesson you did with your group of readers.”

While these events had an impact on me as I remember them fairly clearly, I felt like there were pieces missing from the experience. For example, with the 6th-grade science experiment, the principal never followed up with me to confirm that I did, in fact, have a Plan B for specific lessons involving complicated resources (I did). Additionally, what did a quality Plan B look like? What had more veteran teachers created?

Regarding the 5th/6th content-literacy lesson, what was it about the lesson my principal specifically liked? The study of parts of speech within authentic texts? Or, the fact that we had integrated social studies and reading? Both? Something else entirely?

To be fair, I credit my former supervisors for inspiring me through their actions to pursue the principalship. They did the best they knew how at the time, just as I would have if in their roles. Yet even today, many classroom visits by leaders are haphazard and unintentional in schools. There needs to be a purpose for our visits, a clear distinction between observation and evaluation, and a continuous effort toward collective improvement that everyone can understand and get behind.

The Purpose for Our Work

Instructional walks offer a more responsive and authentic approach for promoting continuous improvement with all educators in order to move a school culture toward student excellence, especially in literacy.

This learning includes principals. I have learned as much and likely more than many of the teachers I have connected with during my regular classroom visits. Up until that point, my background in literacy was limited to the resources I read during my career as an intermediate level teacher and my college coursework.

For example, during a recent instructional walk in a 1st-grade classroom, I observed students engaged in Reading A-Z texts. These booklets were printed out from the copier, maybe not as authentic as an actual book of their choice from the library. Yet I knew my role was not to judge but to notice and note what was occurring through an appreciative lens.

Once I gave my notes to the teacher, I asked how she felt the students responded to the booklets. “Great. They are nonfiction texts, which they love. The kids get to choose from a wide variety of topics within a range of levels. We have more time to confer and coach kids because our classroom volunteers print off the books and set them up for students to select. The kids eventually take the books home to reread.” I responded with how impressed I was with the thought that went into their readers’ workshop.

My initial thinking was:

kids were assigned to one level of text,

the text was chosen for them, and

there was a lack of authenticity or connection.

With an open mind, my understanding improved and the teacher felt appreciated. In addition, I realized the important role that the adult volunteers played in the classroom. They gave the teacher more time to teach and confer with kids while they were reading. Had I come into the 1st-grade classroom with only my pre-existing thinking about reading instruction, which did not include any experience teaching 1st grade, I think our conversation would not have led to a deeper understanding in my end nor the teacher affirmed in her practice.

Through a lifetime of working in schools, one of my most powerful insights and core beliefs is that teachers must be leaders, and principals must know literacy.

- Regie Routman, Read, Write, Lead: Breakthrough Strategies for Schoolwide Literacy Success

In these times of high stress in education, one of the greatest gifts we can give to our schools is a sense of understanding and appreciation for what teachers and students do every day. With instructional walks as a part of our leadership roles, we become real partners in the teaching and learning experience. This leadership practice is a critical strategy for creating conversations around the work instead of being in constant evaluation mode. In fact, it’s the conversations among educators that foster the greatest amount of growth. We will know we are successful when the question evolves from “How am I doing?” to “What are we doing, and is it making a difference?”

Excellent insight from both perspectives...teacher and administrator. Thanks!