Knock on Every Door: Leading Conversations That Drive Literacy Excellence

Preaching to the choir won't move a school toward schoolwide literacy excellence

Someone rang the doorbell and my son answered. From the kitchen, I could hear a campaign volunteer making the case for a political candidate this fall. As I walked up to the door, he handed me a flyer.

The volunteer explained that his preferred candidate is supportive of schools, for example ensuring more funding comes back to public education. I realized that he was promoting a candidate that we already had a political sign for in our yard. When I finally pointed this out to him (literally), he turned around, saw our sign, laughed, and then commented, "I'm sorry, I realize I'm preaching to the choir."

After he left, I wondered how that conversation might have gone had he tried to promote a candidate we did not support. Would I have been open-minded and asked questions about their positions? Or would I have simply said no thank you and closed the door? I applaud this worker for engaging in these interactions. Each doorknock could lead to disagreement or even confrontation. And yet he probably knew that he was going to make the most difference with the people who didn't agree with him.

I share this anecdote as I think about literacy leaders who are also trying to campaign for better literacy instruction for readers and writers. As a former principal, I naturally found my way toward faculty who shared my beliefs: preaching to the choir, feeling good about myself. I had to be intentional about interacting with all teachers around challenging topics, such as how much time to devote to foundational reading skills. Like the campaign volunteer, time spent with individuals who I did not always agree with regarding literacy instruction is where I was needed the most.

Why do leaders avoid these conversations? Because, like most people, we want to avoid confrontation. We’d rather not ring that proverbial doorbell and deal with the uncertainty of someone’s response. It induces anxiety. These discussions can lead to disrupting the peace of our school.

However, this “peace” is really the status quo. It’s the way we have always done things. And that is why schools are getting the results they see. Allowing for things to remain the same means we accept less than excellence, that we are comfortable with some students not being as successful as they could be. All in the name of avoiding some personal discomfort.

Leaders can engage in these conversations with more confidence and calm. This courage comes from being more knowledgeable about literacy instruction, creating the conditions for professional conversations, and using collaborative norms to support productive interactions.

Becoming More Knowledgeable About Literacy Instruction

Leaders don’t have to devour a dozen books about effective literacy instruction to begin in engaging in professional conversations on this subject. A couple of well-written articles can be all that is needed to get the discussion started.

Here are three to start with, from the International Literacy Association (ILA):

The Science of Reading Progresses: Communicating Advances Beyond the Simple View of Reading by Nell Duke and Kelly B. Cartwright (Reading Research Quarterly, 2021)

The authors provide an overview of the different theories of how students learn to read. They then offer a new framework that includes motivation and engagement, executive functioning, and strategy use. Excellent information to know when leaders are presented with the Simple View of Reading as the only theory of action for teaching readers.

Reading Volume and Reading Achievement: A Review of Recent Research by Richard L. Allington and Anne M. McGill-Franzen (Reading Research Quarterly, 2021)

Are you noticing independent reading time is disappearing in classrooms, due to an overemphasis on using a packaged curriculum? This article makes the connection between the amount of time students spend reading and their success as readers. As the authors point out, “proficient reading, like virtually every other human proficiency, benefits through extensive engagement (or practice) with the activity.”

Disrupting Racism and Whiteness in Researching a Science of Reading by H. Richard Milner IV (Reading Research Quarterly, 2020)

When schools move toward more structured and subsequently less responsive reading instruction, who is left out? Milner points out that when motivation and cultural relevance are ignored, students from historically marginalized communities are often the ones who suffer. “If we want to know more about the science of reading, we must carefully examine the who, the racial and ethnic identities and perspectives of those building the knowledge.”

Creating the Conditions for Professional Conversations

Just having more knowledge about reading theories and effective vs. ineffective practices won’t guarantee a professional conversation with colleagues about literacy.

People need to feel safe speaking openly about contentious topics. A sense of trust that someone will not react poorly to an honest comment has to be present for conversations to surface the truth about what people currently think and believe. Once these ideas are brought to the surface, educators can objectively examine a statement or belief through a critical lens.

As a coach, I can create these conditions using a variety of communication strategies.

Sharing working agreements at the start of any meeting.

Describing my role and responsibilities, especially with what I won’t share with an administrator that comes up during a coaching conversation.

Highlighting successes in emails and newsletters, particularly when supporting colleagues in their contexts.

Distributing professional resources to faculty, such as the articles listed previously, to convey my credibility as a knowledgeable educator.

Using Coaching Skills to Support Productive Interactions

What influences how others perceive my ability to facilitate professional conversations is the feedback teachers and leaders share about their interactions with me.

Word-of-mouth might be the most powerful resource for instilling trust and confidence in my ability to engage in interactions around challenging literacy topics.

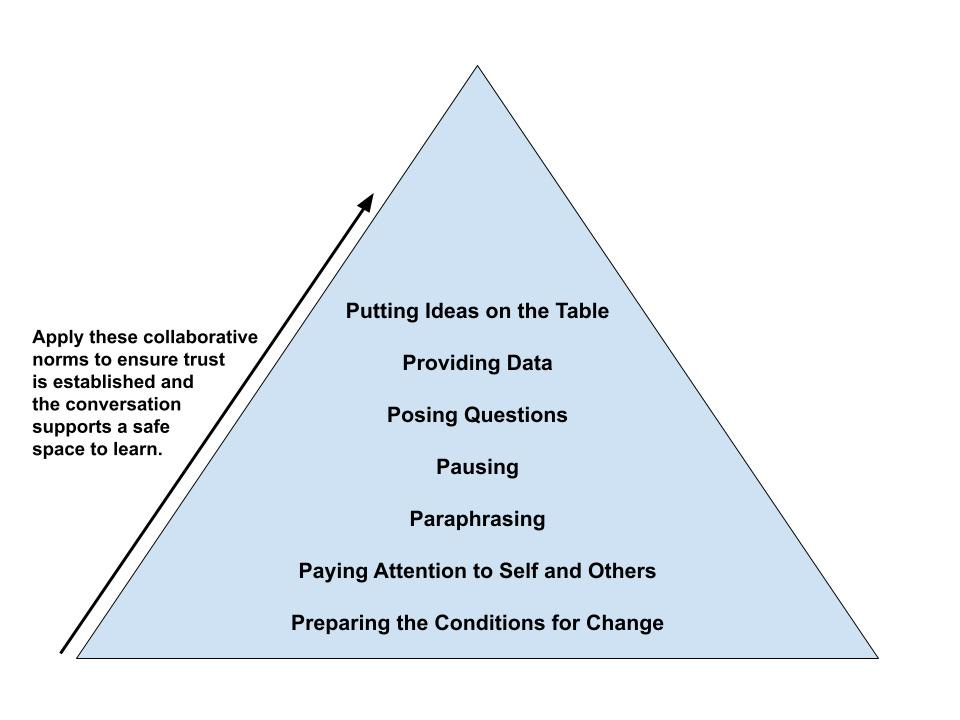

My secret weapon is not-so-secret: coaching skills. In Cognitive Coaching, these competencies are known as “collaborative norms”, and they form the foundation of my interactions.

(Note: I have replaced “presuming positive intentions” with “preparing the conditions for change” to reflect the most current thinking in this area - see “related resources” below).

Leaning on these skills helps me stay above the fray - keeping a conversation at a level where people can still hear one another and maintain an open mind around new ideas.

In the end, the real work of literacy leadership happens in the tough conversations, not the easy ones.

Just as the campaign volunteer knocked on doors, uncertain of the reception, literacy leaders must engage with teachers who may not initially share their perspectives. These are the moments when real growth and meaningful change occur. By deepening our knowledge, building trust, and using coaching skills, we can approach these conversations with confidence, knowing that they are critical to improving instruction for all students.

Found this post helpful? Share with a colleague.

Related Resources

A coach colleague recommended the article “The Problem with Positive Intent” to me. The author, Ruth Terry points out that the problem with assuming good intentions is that not every person experiences the same privilege, especially people of color. This one piece changed how I interact with others as a coach.

The seven collaborative norms comes from the work of Robert Garmston and Bruce Wellman, from their book The Adaptive School. You can learn more about them from the Thinking Collaborative website.

In a post about the SoR movement, “The Science is Anything But Settled”, I suggest that seeking to understand is a best step forward in resolving these heated debates (including “presuming positive intent” :-/). What does seem to remain current from this post is doing our best to understand where the other party is coming from.

Premium Post

[This is an experiment - my plan is to restart my paid subscription for readers who would like access to additional content. Below is a link to an article that typically would only be available to full subscribers. Please share any feedback with on how this plan resonates with you by hitting reply to this post.]

In the linked article “Navigating the Science of Reading: How to Hold a Professional Conversation About Teaching Readers”, I share my experience of trying to enlighten a literacy expert with research the contradicts her current position. Unsuccessful, I reflect on three conditions for listening and learning that support more productive conversations around this challenging topic.

I don’t envy your job, Matt. I’ve

seen polarization in education before in my over forty years in the field. But it’s always been place based, horizontal—never really a debate over “truth” but about “philosophy.” This round is horizontal and vertical, reaching to the inner sanctums of state legislatures. Politics has always been a debate about “truth,” not about facts. SoR isn’t about facts. It is about truth. One side claims it, the other denies the claim, and facts become negotiable.

I’ve not seen you in action. However, through your writing and our conversations, I have formed conclusions about your dispositions, knowledge, and coaching skills. I think you are a model of an active agent with potential to make horizontal breakthroughs in standoffs with hope of disrupting the vertical politics.

Having worked in professional development myself, I understand the distinction between advocacy for a method and advocacy for teachers, for scaffolding their thinking about methods for themselves. The teacher’s capacity to use the evidence in front of them day in and day out in the actions and emotions of our precious children. If teachers need evidence of learning, that’s where it exists. Experiments result in evidence of theory, not evidence of good practice.

I love that you are thinking about turning back on the paid feature. In addition to paying you for your time, you’re partially ensuring you can “presume good intentions.” Professionals doing development work spend their workdays making contributions to the future and earn their keep. We need you, Matt.