Less Teaching, More Learning

Creating Space for Natural Learning in Literacy Instruction

During the first gallery night in our little artist town of a city, I stopped into the shop where my daughter worked. Behind the register, she was playing a game on her phone. "Slow night so far?" She nodded. "Did you bring a book?" She shook her head. "I left it at home." Then I remembered that I had a copy of Suzanne Collins' latest entry in the Hunger Games series waiting for me at our local independent bookstore. "If I bring it over, will you read it?" She nodded.

After dropping the book off and visiting other art studios, I stopped back in to deliver a late dinner of pepperoni pizza. She was halfway through her new book. "Whoa...slow down," I joked. "If you want me to read..." she smiled, shrugging.

I'd like to say every interaction I have with my teenage kids is a positive one. But like many parents today plus well-meaning educators, I have sometimes taken a more critical approach when dissuading them from spending too much time on their smartphones.

For example, we tried as a family to monitor our screen time average together and talk about the results. My wife and I have imposed limits on when apps can be accessed, such as shutting down social media at 9 p.m. I think these more top-down approaches have their place. But without a positive and productive why behind the policy or healthier replacement behaviors, they can come across as mandates born out of fear.

I’m concerned that we educators aren't creating compelling learning environments that can compete with the myriad distractions vying for teenagers' attention in today's world. Instead of creating more space for crucial conversations around this topic, we add things to their lives when we want to change the outcomes for the better: new curriculum, more instruction, additional assessments. Even a phone ban at school, while well-intended, dismisses the opportunity to have meaningful conversations with students about this issue. A key topic where instruction would genuinely benefit, and we ignore it.

Thinking more broadly, what if we considered the possibility that all of our instructional attempts are interventions? And that any intervention is actually an interruption in the learning process? This would require the belief that people, especially young people, are natural learners and are capable of a lot more individually and collectively if we allowed them the space and trust to do so.

I'm not advocating for a laissez-faire approach to education, a 'let them learn and see what happens' mindset. I'm reminded of the middle-grade novel by Andrew Clements, The Landry News (affiliate link), in which a burned-out teacher instructs his students from behind a newspaper. The kids are surrounded by print but no pedagogy. The students protest the lack of instruction by chronicling their frustration through a classroom newsletter. This authentic literacy experience occurred in spite of the teacher's abdication of his duties.

What I am exploring here is an approach to teaching readers, particularly at the middle and secondary school level. A sort of anti-intervention mindset to literacy instruction; a Tier 0 approach in which the only guidance and modeling is deemed necessary instead of obligatory, i.e., the board-approved curriculum program.

What might this look like?

The first day of a unit of study devoted to discussing an essential question as a whole class. It can be followed by an introduction of the project or performance task students will engage in to show transfer and understanding of the key ideas and skills.

Formative assessment that positions the students as first evaluators of their work. For example, students could be empowered to select a response from their reader’s journal to expand into a book review or a literary analysis, depending on the age of the students.

While the students are reading, the teacher can use an observational form that helps them monitor reader engagement and identity. (See the Monday Morning Memo #2 for more information.) The teacher can couple this data with students’ achievement results to develop a richer picture of who they are as readers.

What these ideas have in common is we’re not adding anything to the curriculum. In fact, if a teacher were to apply these approaches, they would be lightening their instructional load. The students are empowered to take control of their literacy lives.

I didn’t have to coerce or shame my daughter to put her phone away. I didn’t have to create a mandate of when and for how long she could use her phone. I knew what she liked to read, I provided access to those texts, and I checked in on how things were going without the need to quiz her on the content. I think students, as much as anyone, want the opportunity for choice and to be treated with respect.

Related Resource

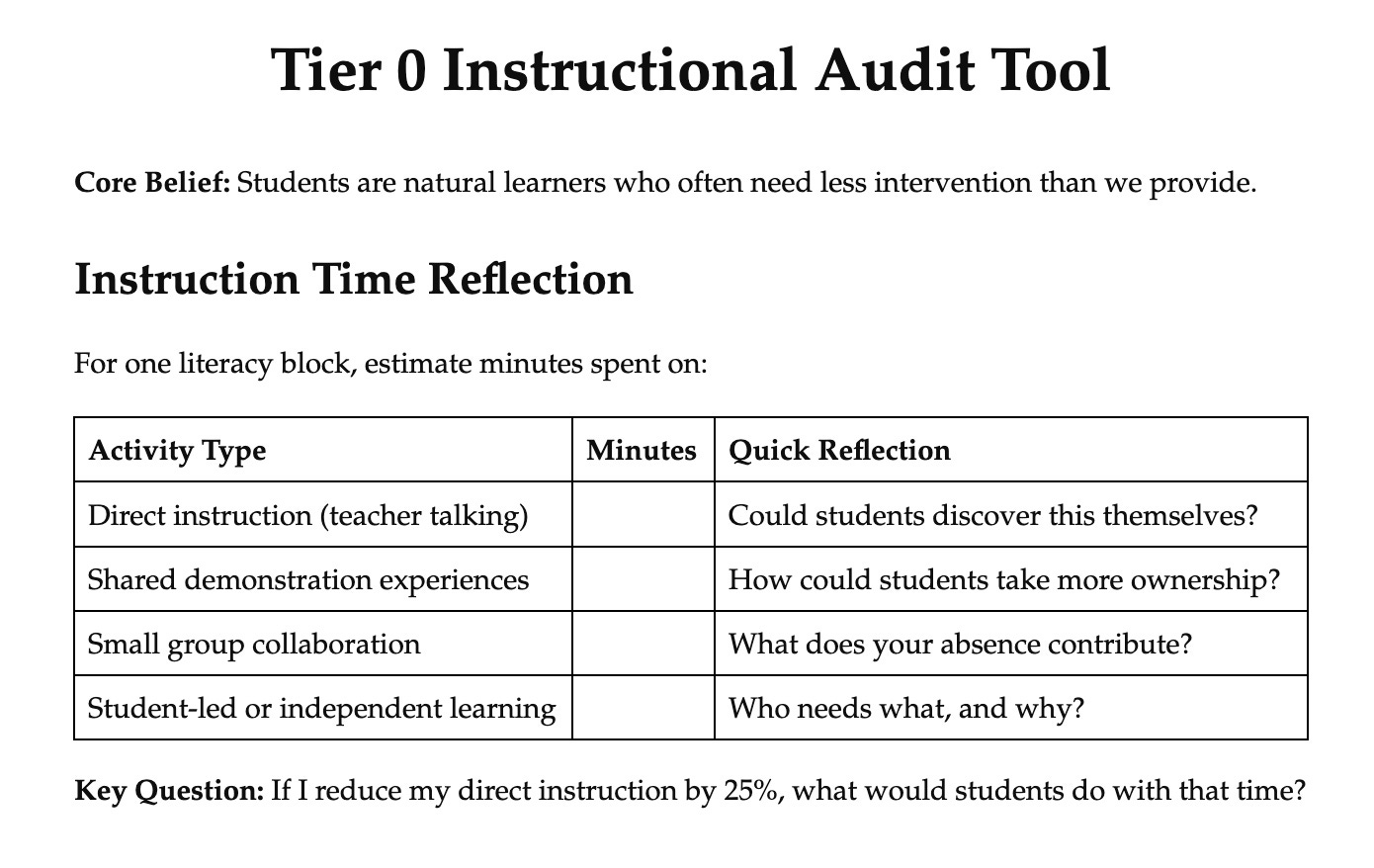

For the next Monday Morning Memo, I will be sharing a Tier 0 Instructional Audit tool for full subscribers. It is an educator’s guide for reducing the amount of time spent teaching in favor of more opportunities for student practice and learning.

Nice work Matt. Beautiful writing.

Enjoyed your narrative. Btw, your daughter is perfect.