As a faculty, we were learning how to use Bloom’s Taxonomy (2001 version) to analyze the cognitive level of an instructional task. Why are we doing this? Didn’t we cover Bloom’s in college? While leading this PD, I could imagine these questions popping up in the minds of a few teachers. Thankfully, faculty seemed engaged overall.

Part of our professional learning involved evaluating the level of thinking of an activity I purchased on Teachers Pay Teachers. It was a worksheet that asked readers to locate figurative language in their independent reading texts.

On the surface, this task appeared authentic. “Try not to insert your teacher lens into the activity. Look at through the six levels of Bloom’s taxonomy and decide to what degree of complexity are students being asked to think.” The consensus: only understanding, the second lowest level. We closed out our time together by affirming that with the proper mindset and resources, the teacher can (and should) be the primary arbiter of what flows in and out of our classrooms.

Innovation at the Expense of Expertise

In the spirit of innovation, we feel constantly called to investigate a new practice, philosophy, or approach to instruction. Here is just a smattering of the latest:

Trauma-informed teaching

Social-emotional learning

Mindfulness

The Whole Child

Standards-based grading

I believe (with my limited knowledge) that all of these initiatives have merit and deserve at least some consideration to have a place in schools.

However, my worry is that we focus on these areas at the expense of the reason schools exist in the first place: to educate all children toward personal development and a more democratic and just society. This means kids need to know how to read, write, think and communicate in addition to an appreciation and the application of other core areas.

Ignoring this responsibility happens quite easily. It’s much easier to purchase a product when planning professional learning than to devote our limited time to improving and sustaining our collective instructional capacity.

May I have your attention, please?

Education is hardly the only profession that suffers from a lack of attention devoted to continuous improvement.

For example, we may assume that police officers received extensive annual training on how to handle firearms. A report by NPR, however, found that “determining who's the good guy in those types of situations can be difficult,” and “what's needed is better police training and public conversation about how police work.”

In complex professions, why isn’t continuous improvement in these critical areas a priority? I believe a part of it is that ongoing professional learning can be perceived as (or actually is) boring.

“If we covered this last year, why are we reviewing it?”

“I learned this in my graduate work.”

“It’s what I do every day. Just let me teach.”

These statements may sound familiar. They can also pull leaders’ collective attention away from what’s necessary and start to doubt how professional learning time is spent. Leaders question their beliefs when a few teachers begin to feel uncomfortable. Conversations then spiral about what the focus should be for future professional development, which too frequently leads to selecting a program, resource, or new initiative that does not address the real needs of the students and staff in one’s school.

Continuous Improvement, Revisited

Whatever it is a school decides to focus on, there should be a long term commitment to these efforts. Three to five years is a reasonable timeline. Without sustained continuous improvement, teachers don’t have the time or opportunity to fully embed promising practices into their classrooms.

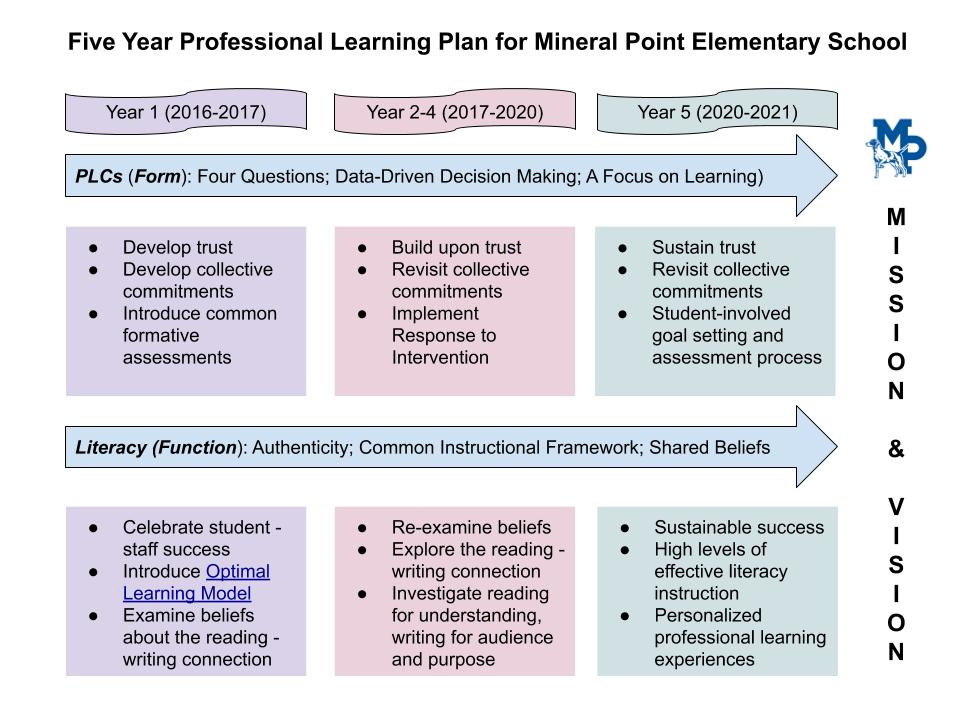

Here is one example, an initial five year plan we developed at my current school.

This plan was not written in stone. In fact, we’ve adjusted it every year in light of student assessment results and teachers’ feedback about the professional learning provided.

One way to gather feedback about the work is through periodic surveys. For example, we are currently in Year 2 of our district strategic plan that is focused on developing a literacy-rich curriculum in all content areas. Last year we explored promising reading instructional strategies while starting to map out our social studies curriculum. This year has been a lot of direct instruction on how to write a quality unit of study.

Feedback about what’s going well and what could be improved was requested. Teachers said they appreciated the resource sharing and coming back to what was learned before. They requested more time to actually write and collaborate. With that feedback in mind, we are devoting our final PD day for teams to do this work.

This information is guiding discussions at the leadership team level. Specifically, we realized that we need to bring in some critical friends beyond the school to help us initiate critical conversations about consistent ELA expectations for students at every grade level. These expectations should be coupled with promising literacy practices. Likely this work will take the remaining three years of our plan.

Stepping Back, Moving Forward

“If we hadn’t started with social studies, then we would have been able to focus more on reading instruction.” Our leadership team paused to consider this comment. We were reviewing our ELA test results from the last four years, noticing a slight decline. “Yes, but why can’t one support the other?” responded a colleague.

We decided that we needed to frame this professional learning going forward as one and the same: that we can continue to improve in our abilities to teach readers and writers and develop quality ELA and social studies curriculum. “Now that teachers know how to write a unit of study, let’s take a step back and really dig into our literacy expectations.”

Taking a step back…how often do we hear this in education? Not enough. This work is messy and at times incredibly difficult to determine a focus, like playing whack-a-mole in an arcade. It’s much easier to move toward a more clear target and buy a program. Maybe that is why schoolwide literacy excellence is uncommon: it takes years of clarifying goals and revisiting expected outcomes, rife with debate about the best way to reach the destination. Yet this is the work, the right work, and it is worth it.