Lately I’ve been writing the following acronym at the top corner of my meeting notes:

S.A.F.J.

It stands for “Stop Assuming, Fixing, Judging”. It’s my reminder to listen to others without trying to solve any perceived problems or feel obligated to reply with my opinion. Instead, I am focused on being more curious and to facilitate conversation.

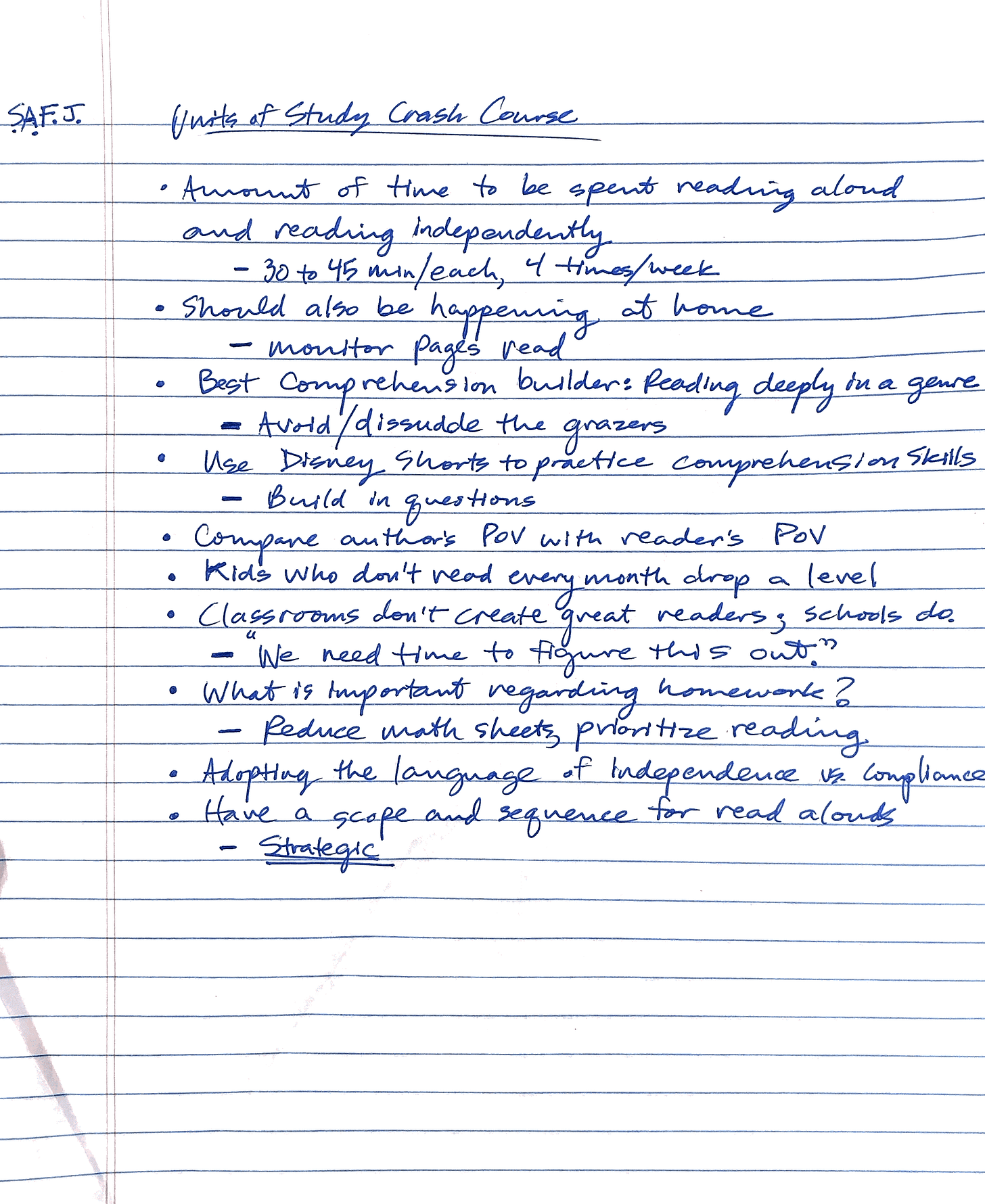

I did my best to apply this approach recently; intermediate teachers met to discuss the recent workshop they attended. It was led by Mary Ehrenworth, one of the developers of the Teachers College Readers & Writers Project.

Yet a few minutes into the debriefing, I reverted back to my still-default stance of judging. Example: “Classrooms should devote 30-45 minutes to reading independently daily,” shared one teacher. “That includes time reading in the content areas, like social studies or science, right?” My question was leading. I was looking for confirmation of my beliefs. Whether I was right or not, I wasn’t fully listening.

Starting with Trust

Being self-aware, I confined myself to mostly note-taking for the rest of the meeting.

Silence and active listening builds trust. The speaker believes you are listening to them. Taking notes shows we value what they have to say and share.

At another level, the opportunity to speak in front of colleagues allows the true community to start to reveal itself. Parker Palmer talked about this. In his article “Thirteen Ways of Looking at Community”, he noted that “community is not a goal to be achieved but a gift to be received”. Palmer expanded on this concept, explaining how a culture focused on being the best can inhibit trust and connectedness.

When we try to “make community happen”, driven by desire, design, and determination - places within us where the ego often lurks - we can make a good guess at the outcome: we will exhaust ourselves and alienate each other, snapping the connections we yearn for. Too many relationships have been diminished or destroyed by a drive toward “community building” which evokes a grasping that is the oppositve of what we need to do: relax into our created condition and receive the gift we have been given.

With constant pressure to achieve, it becomes too easy for leaders to push for outcomes we perceive as the right way to proceed. The paradox is, providing time and ensuring equity of voices being heard is the more winding yet truer pathway toward collective understanding and schoolwide coherence.

Supporting Community Through Stucture

Note-taking and pausing are important beginnings for building trust. But they won’t suffice alone without parameters and purpose for how we engage in dialogue.

The outcome of the teacher debriefing was to clarify our understanding to then share with the entire faculty at the next staff meeting. We were able to achieve this through co-created collective commitments for how we interact with each other. Important ideas came out of the conversation, such as teachers requesting more time to work together.

Yet even collective commitments will not support community withour a common purpose. What are we working on, and why does it matter?

Jill Harrison Berg and Joran Weymer offer a variety of structures for shared leadership toward purposeful work in a recent Educational Leadership column.

Developing a year-long plan for professional learning in the summer prior with a leadership summit and inviting teachers to lead some of these opportunities.

Designating some faculty members as teacher leaders on collaborative teams, providing them with time and professional development to build capacity.

Using self-assessment and reflection tools to gather information in order to make data-informed decisions about the professional learning journey during the year.

Berg and Weymer concede that sharing some of the leadership responsibility “may feel risky for principals”. Yet to not involve teachers in shared decision-making creates risk too, such as making avoidable mistakes because we went forward alone.

In our school, we’ve started sharing the responsibility by having teacher teams lead the staff meetings. They develop the agenda, ask for items to discuss, and building in time for sharing an innovative practice with colleagues. I also have a running agenda item, “Principal Update”, where I revisit important topics and introduce new ones.

Stepping Back, Stepping Up

During our faculty meeting, the teachers who attended the workshop did a wonderful job sharing the information. They phrased the recommendations, such as the need to increase read aloud and independent reading time, as opportunities to build on the good work we have already accomplished instead of framing our reality as inadequate.

Then I introduced a teacher-suggested strategy to start communicating about ELA expectations: writing on a Google Doc the mentor texts and keystone books each grade level relies on for reading instruction.

In small groups, there were questions about whether a grade level could “claim” a book. “You can pull so many lessons and model reading strategies from one excellent text,” noted a teacher. I sat and listened, trying hard to not agree or disagree and instead acknowledge what the teachers were saying.

The conversation was largely positive, possibly/partially due to my offer to buy as many of the texts they needed for reading aloud and independent reading. To a larger extent, there is an increasing understanding that this work is driven by the teachers. They are requesting more time, more texts, and more clarity of expectations. This doesn’t happen without support along with clear direction for the need to articulate our ELA expectations schoolwide.

At some point, when I’ve listened extensively without judgment, I will need to point our collective attention toward our beliefs and commitments as we discuss preferred texts and tasks. The direction might be clear. The journey is still being decided.