“Be curious, not judgmental.”

- Walt Whitman

We live in a society that assigns blame to a person or group for almost any problem. Consider those who invaded the Capital last week. Much of the initial blame was directed at the 45th president as well as the insurrectionists (rightfully so). But these individuals are not generally taking responsibility. So people look for easier targets.

Some pundits are now pointing toward parents and teachers for failing to guide our former youth on how to think critically. For example, Alfie Kohn posted a series of tweets in which he wondered publicly about the formal learning experiences of those who participated in the events at the Capital. For example:

It is interesting that Kohn does not bring up the advent of standardized testing (one of his favorite punching bags) as a reason for reduced capacity to think. Especially in the beginning of the testing movement, schooling became a quest for one right answer. When kids became adults and realized the world is too complex for simple solutions, it is not surprising that some found solace in a carnival barker offering dangerous yet clear ways to deal with their perceived plights. This does not assign blame to standardized testing (see how easy it is?), yet it is an indicator of what our society values.

Commentators thrive by pointing to singular reasons for society’s problems. The reality, however, is this is a systems issue.

Many educators learned about the concept of systems when they were trained in Response to Intervention, or RtI for short (a proactive approach for accelerating struggling students by supporting them with more time and resources). Here is roughly how the system works:

If a smaller percentage of kids are struggling to learn, and the distribution of kids is similar across all subgroups, then we work with these individual students.

If a larger percentage of kids are struggling to learn, and the distribution of kids is centered in specific subgroups such as poverty or race, then we work on the system.

The big system in our case is the school itself: classroom to classroom, core instruction. Unfortunately, too many systems fail to take hold and grow because of low investment in resources, along with the large amount of attrition of teachers and administrators to other schools or even out of education. So, when there is little direction or consistent leadership, any target will do (see: standardized tests). Teaching exclusively to standards helps us feel successful, even though we may be ignoring some of our students’ specific needs.

Two Essentials for Systems to Work

If we want to cultivate important skills like critical thinking with our students, and I believe we should, then we must develop systematic approaches for better ensuring its inclusion. Two essential qualities for working on systems is communication and collaboration.

Effective communication helps us share ideas about what works and what does not for our students. This involves being able to openly admit that we do not know something, and to be willing to consider the possibility that colleagues might have better ideas.

This is not easy. So much of our identities as educators includes personal responsibility for student success. When kids fail to meet the mark, we assign blame to ourselves, at least internally. Maybe we openly complain about outside factors, such as home environment or too much screen time, but deep down most educators point the finger at themselves.

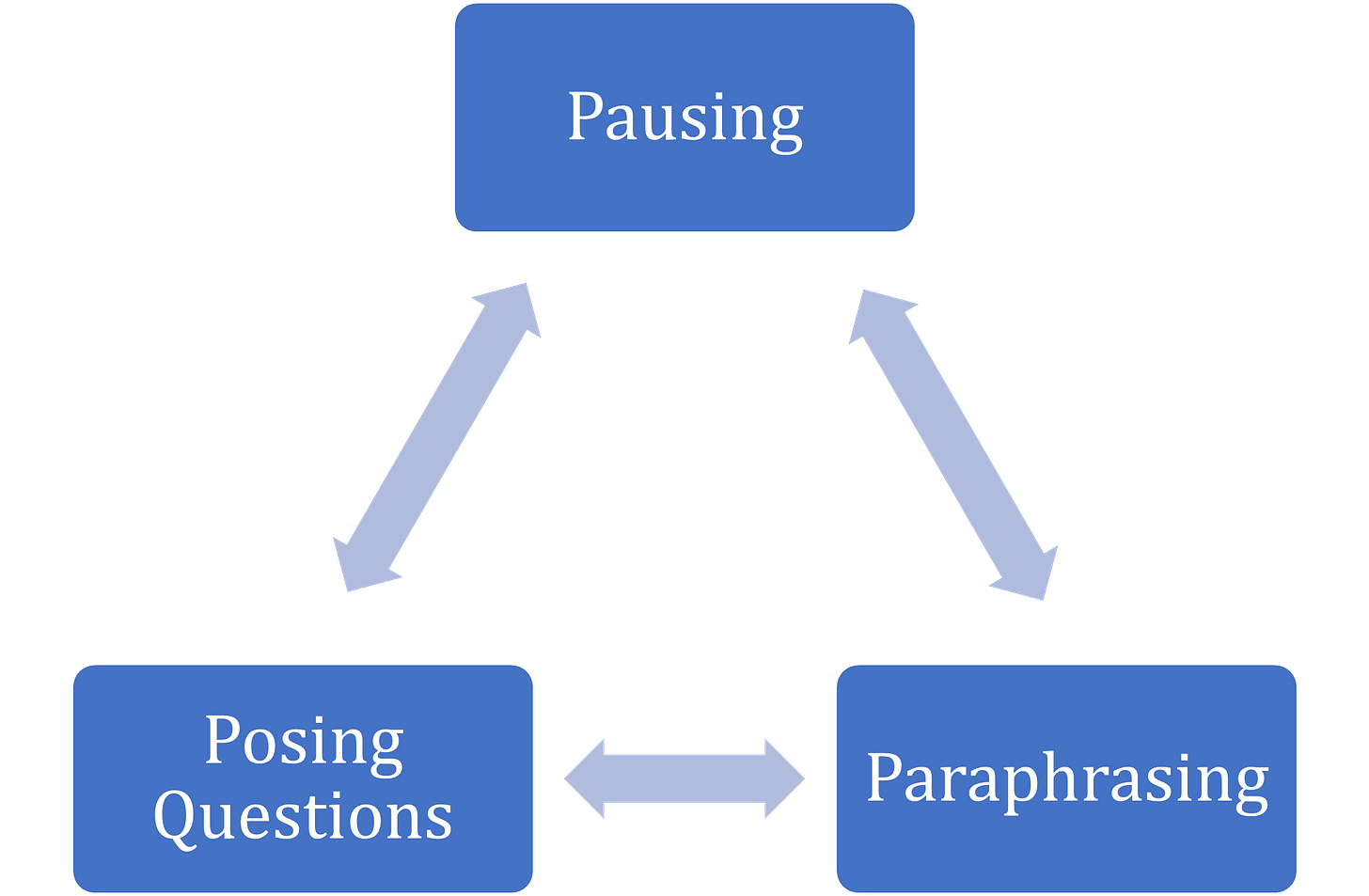

But if we have a multitude of ideas available along with a culture that supports innovation and mistake making as part of the process, then we are not alone in our responsibility. It is a shared experience. That is why we advocate within my own building the development of key coaching skills. Teachers need tools to be able to support each other. The three micro-skills below are reviewed often in our school, from the world of Cognitive Coaching.

All three skills help us communicate more effectively because we avoid judging. We are instead curious about what the person is saying, or we show we are listening by summarizing what we heard. Pausing gives people space to process their thinking. Even the kids benefit when these coaching skills are introduced in the classroom community.

Communication is supported through effective collaboration. The coaching skills become the norms for our time together. In addition, we model and develop structured routines for how to collaborate. These protocols remind team members to celebrate successes. They also “slow teams down” so they can more effectively examine student learning artifacts and develop better conclusions about the impact of their instruction.

Below is our most up-to-date template for team meetings, adapted from Kim and Gonzalez-Black (2018).

These skills and strategies do not guarantee that critical thinking or any other outcome is more of a focus within our curriculum. That direction would come from a schoolwide expectation. What these approaches do is to systematize our work on behalf of the focus. They serve as scaffolds for successful interactions among faculty. We are a more adaptive and nimble organization when the spread of ideas flows more freely.

If coaching skills and team meeting protocols become institutionalized, effective communication and collaboration become part of the culture. They last beyond any one leader. Instead of blaming someone, the responsibility is on the system. Systems can be adjusted accordingly (and much more easily) when we are not getting the results we desire.

Recommended Reading and Resources

I do appreciate some of Alfie Kohn’s articles, such as his latest article about standardized testing. (h/t Regie)

The Whitman quote comes from the Apple+ series Ted Lasso. A funny show, full of optimism and wisdom.

UCLA Center X offers virtual professional development around the tenets of Cognitive Coaching. I am participating in their book study this semester.

For more information on supporting teams, check out this conversation I had with Anthony Kim, co-author of The New School Rules.

Speaking of community, the fourth writing tip was posted on Tuesday along with an invitation to join our virtual writers group (full subscribers only).

Thank you for your readership and leadership. I meant to get this out yesterday, but I have been helping my kids develop their final project for our collaborative Genius Hour project (we are planning a treehouse). Sign up today to read more about this experience later this month. In February, I will also be publishing an interview with the authors of The Genius Hour Guidebook.