Teaching for Today and Tomorrow #engaginglitminds

Can I be real here for a moment? I teach first graders. It isn’t often that I have paused to note that these amazing human beings are going to grow up and become parents. I’m striving hard to ensure they can read and write at grade level and know their math facts fluently. Add to that the tremendous pressure of new mandates, initiatives, curriculum and the expectation of covering “xyz” between September and June...whew! I think it is forgivable if, like me, you sometimes get caught up in the “doing” and forget to stop and reflect upon these truths.

And yet we must pause and reflect. For example, on page 32 of Engaging Literate Minds, I appreciated the following,

“‘If you tell them, they don’t think about it as much and won’t remember the next time. If they figure it out, they’ll remember better.’ Laurie’s students are bona fide teachers (and we should probably not forget that many of them one day will become parents).” (Johnson et al, 2020)

I paused, and then reread. The two things that really drew me in were:

The fact that the children we teach today may very well become parents.

That if you figure something out yourself you are likely to remember it better.

As educators, we must pause and reflect that these are inherent truths. I love that this chapter is devoted to noticing and recognizing that “We’re All Teachers Here: Distributing Teaching and Learning.”

“This focus on teaching students to take the initiative in acting strategically, rather than merely teaching them strategies, cuts across all aspects of classroom life.” (Johnston et al).

Acting strategically. Not, “Knowing and being able to list off 13 different reading strategies to use when encountering a new word,” but rather, “Having the initiative to think and act strategically”. Now THAT’S good stuff!

So how do we begin to achieve that? As the authors reiterate time and time again, it’s primarily about the language we use. We have to know and understand that the language we use prompts children to take responsibility for recognizing and solving problems. Questioning stems like:

“What have you tried?”

“What can you do to help yourself?”

“What are you noticing?”

There are many ways to place the onus on the child to do the thinking and problem solving.

In addition, I think it’s taking the time, as mentioned in the book, to intentionally set the stage at the beginning of the school year, that EVERYONE in the room is a teacher. That noticing, thinking and wondering are valued. Actively promoting and fostering the notion that a growth mindset, asking for help, working through problems, are signs of intelligent engagement. This idea of distributive learning and dialogic talk within the classroom lends so easily to what most of us really want for our students today, tomorrow, and in their future.

Stopping to take the time to reflect and get re-grounded has given me a renewed hope for what can truly be in my classroom that will promote the advanced level of prosocial reasoning that Johnston et al elaborated on in this chapter. This “valuing of their classmates and the community over one’s own personal needs” is something the world inherently needs. Now, perhaps, more than ever.

When we as educators think less about just passing the child on to the next grade, and more about creating informed, civic minded, and socially contributing members of society today, we will have entered a realm of teaching that is beneficial to all.

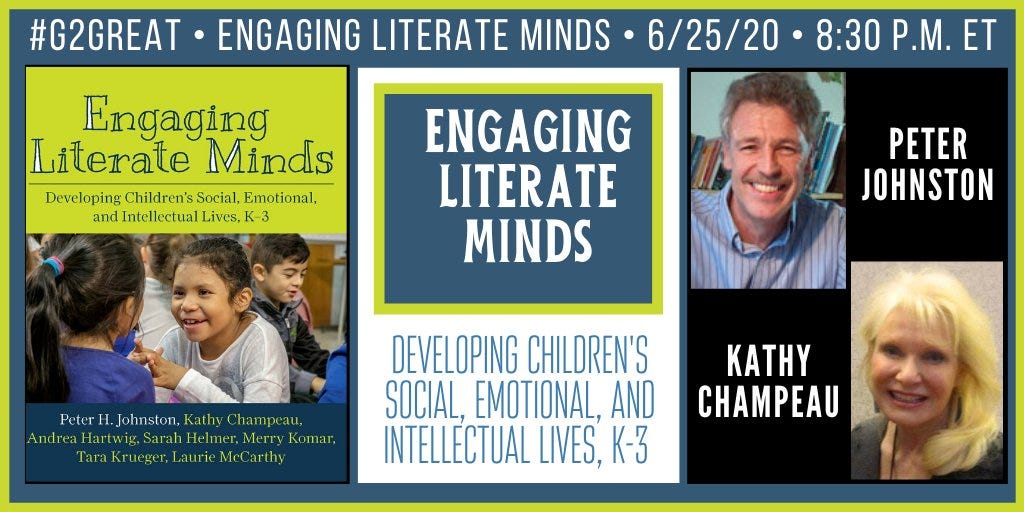

This post is part of our 2020 Summer Book Study. Find all previous posts and more information here. Also, we will discuss Engaging Literate Minds every Wednesday at 4:30 P.M. at the newsletter. Sign up below – it’s free!