The Reciprocity of Executive Function and Literacy Development #engaginglitminds

In education, it may be tempting to simplify and compartmentalize our teaching. It is easier to think of our day as a block of time for reading, a block of time for math, a block of time for working on social-emotional skills, etc... However, when we teach in such an isolated way our students struggle with generalizing their learning to different situations. Students benefit from the integration of various subject areas, working in a cross-curricular way, and being shown how to apply their social-emotional learning to a variety of settings and situations.

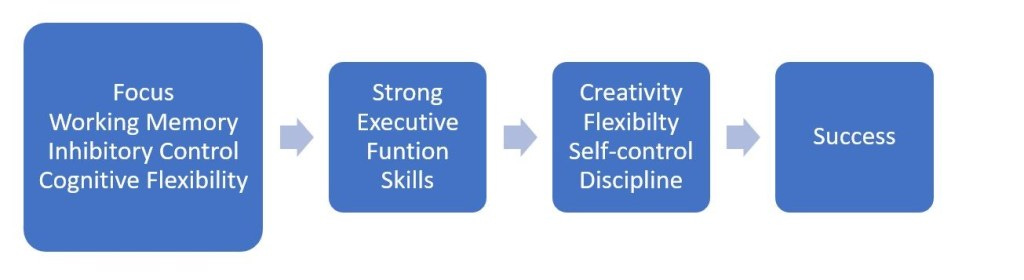

When we think about children's behavioral development and more specifically their scope of executive functioning skills, we can see how it directly correlates to a student's academic success. We can help students improve literacy processing skills by boosting their executive functioning skills and we can also use literacy tasks to help students improve their executive functioning skills.

Engaging Literate Minds: Developing Children's Social, Emotional, and Intellectual Lives, K-3 (2020) includes a quote from Adele Diamond and Kathleen Lee in which they highlight the skills needed to be successful:

creativity

flexibility

self-control

discipline

The epicenter to all four skills is executive functioning which encompasses four components.

Focus- Students need to be able to stay focused on their learning despite the many distractions in a classroom setting.

Working memory- Students need to be able to make connections among ideas, take on different perspectives, remember what happened earlier in a text as he/she continues to read, remember plans, rules, procedures, etc.

Inhibitory control- As human beings, there are times when we really want to do something that we shouldn't do, and with effort, we are able to choose to do the thing that we need to do. For example, instead of a student calling out or hitting, they take the time to think about what the more appropriate response would be.

Cognitive flexibility- Students need the ability to manage all of these processes and make changes depending on goals and the situation.

The authors of Engaging Literate Minds write that as children enter kindergarten, "children with better executive function in the fall are months ahead in their literacy, math, and vocabulary by spring, regardless of their initial level of attainment" (p. 72). With the knowledge that executive functioning development can be used as a good predictor of academic achievement, we can see the importance of intentionally planning and teaching for the development of executive functioning skills.

What I would like to do here is highlight ways in which teachers can aide in the development of executive functioning skills and what that support might look like in the context of daily literacy learning. The following vignettes describe some of my most challenging students, but they are also the students that have taught me the most. (Names used are pseudonyms.)

Improve language development

One area in which we can support students' growth in self-regulation is to help develop students' language skills. Not only will self-regulation skills improve but increasing language skills will boost literacy skills as well. We can see how self-regulation, language, and literacy development are all interdependent.

Vanessa

Vanessa was a selective mute, with high anxiety, who had limited oral language skills as well as severe articulation delays. When reading, if she came to a word she did not know, her immediate response was to cry and put her head down for the remainder of the lesson.

Through a problem-solving team, a plan was developed to give her the words she needed to be able to continue with the task at hand. As a temporary support, I taught her an appropriate way to appeal. When she came to a word she didn't know, she simply had to say, "help." I am using the word "simply" in a tongue-in-cheek way. Asking a student who rarely said anything to verbally appeal for help is anything but simple. I took the time to model what it would look like to come to something tricky and say "help", and even said "help" for her when she stopped at a word so that she could see how I would support her. By the third day, she was very quietly asking for help on her own.

Our next step was to take this new skill of appealing for help and show Vanessa how to apply it to different contexts in the classroom.

Learning environment

We can impact the rate of executive functioning skill development by the way in which we orchestrate the student's learning environment. Happiness in the environment increases the capacity of the working memory and executive control and decreases anxiety which can inhibit executive functioning as well as other cognitive functions.

John

John was a first grader who expressed his frustration through yelling, using profanity, and/or throwing objects. He spent much of his time in the office missing many learning opportunities in his classroom compounding his struggles in school. On the first day that I worked with John he told me very plainly, "I will not read &%$*! books" as he pushed the basket of reading materials on the floor.

After that first painful lesson, I thought long and hard about what I could do to change the learning environment to make him feel happy to come to our learning space. The first thing I decided to do was clear the working area of any materials. During our next lesson together, I made it clear to him that during our time together he would become a reader and a writer, and we would use lots of teamwork to get him there. I was able to have a conversation with him for about 15 minutes. I learned about his likes and dislikes, learned about his family, what he liked and did not like about school, and what he found challenging or easy.

Before he left, I let him know what learning would look like with me. I would choose books that I knew he would be interested in, I would only choose books that I knew he could be successful with, I would give him some opportunities to choose books that he wants to read. I let him know that it was not just about me teaching him how to read and write. He would also be teaching me about himself and he would even teach me how to be a better teacher.

Following that lesson, I had to be so careful about everything I did so that John could see that I was following through with our plan. It took about two months before I gained John's trust enough that he would come happily to our learning space and would attempt things he was unsure of with his new-found confidence.

The classroom teacher and I communicated frequently so that we could replicate environmental changes that increased John's happiness in both settings.

Make learning meaningful

Students need to understand the purpose of their learning. When our brain does not know the outcome we are striving for, it uses all its energy trying to figure out the purpose rather than attending to the task and actively learning. Meaningful and authentic projects such as book making and inquiry projects can help students to attend better to tasks, make connections, and exercise their working memory.

Jose

Jose was a second grade student who was bilingual with English as his second language. He moved to the United States when he was in kindergarten and by second grade, he had a significant amount of English vocabulary under his belt and had gained control over a variety of English language structures.

During writing time, he often had a blank page or very simple sentences. Jose's teacher took advantage of writing conference time to talk to Jose about creating a book centered around something that she knew he was passionate about. Jose was an expert about different types of construction vehicles as his father worked in the field of construction. Daily, Jose shared much of his knowledge about construction vehicles with his teacher and classmates. As mentor texts, his teacher shared nonfiction informational books created by various authors including student authors.

Through his new purpose of creating a product concerning something that he is an expert about, Jose became immersed in creating his book all about construction vehicles. He started to look forward to writing time. His writing transformed from simple disconnected sentences to several sentences written about each construction vehicle. As his teacher continued to support ways to think of meaningful topics to write about, Jose took on the role of author and eventually needed little support in choosing topics.

In summary

"These relationships are constant reminders to us that while we are teaching literacy, more importantly, we are teaching children. The ways we go about teaching literacy affect children's broader development and the ways we attend to children's broader development affect their acquisition of literacy" (p. 74).

Knowing that improving executive functioning skills has a substantial impact on academic progress, educators should plan to address these skills in an intentional, rather than incidental, way. As we teach students strategies to help them to develop executive functioning skills, it is important to help them to apply that strategy in a variety of contexts.

This post is part of our 2020 Summer Book Study. Find all previous posts and more information here. Also, we will discuss Engaging Literate Minds every Wednesday at 4:30 P.M. at the newsletter. Sign up below – it’s free!