To Build Trust, Lead with Humility

For schools to learn together, faculty have to trust each other. They need to know that their colleagues and leaders will support them when they share their challenges and ask for help. It feels frowned upon in education to say, "I don't know." We are expected to be so good as educators, that to admit that we are less than what others might expect of us is a risk.

Where does trust start? I believe it is with the leader. We built this trust by being trustworthy. It begins by acknowledging our own challenges and how we are seeking to improve with help from others. By being open about where we fall short, others might too.

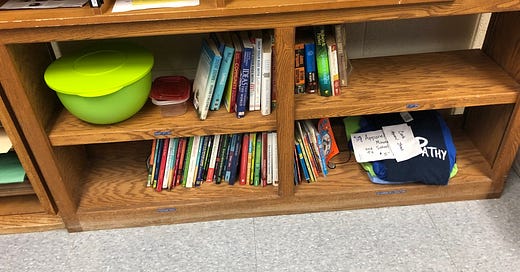

Example: I tried to create a lending library in our staff lounge. Books were brought from home, donated to the cause of encouraging more teachers to be readers.

This is how the space stayed from the beginning (not including the Tupperware bowls and t-shirts). Why? Maybe because it was my project. I didn't ask for help or input. As I think about it, I also didn't invest in the space either - only second-hand books.

So I found an idea in Becoming a Literacy Leader by Jennifer Allen: purchase a gift card for a physical book store and have teacher leaders select titles the staff would want available.

After a trip to Barnes & Noble by three of our teachers, they outfitted the lending library with many new books by authors such as Jacqueline Woodson, Ruta Sepetys, Elin Hilderbrand, Chris Cleave, Nicholas Sparks, Amy Bright, and Herman Koch. Books I would have likely never thought to include.

My wife, who works in my building, saw this space and immediately grabbed Where the Crawdads Sing by Delia Owens. As soon as she was done reading it, another teacher snagged it, read it, and then left a sticky note on the cover with her short recommendation.

Building trust through humility should happen with our words as well as our actions. To follow up on the last example, I recently finished The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead. At a staff meeting, I wanted to take a moment to use this book as an entry point to briefly discuss and encourage cultural responsiveness in our classrooms. In the past, I would have said something like the following:

I recently read The Underground Railroad. I've chose to expand my reading diet by diversifying the authors and topics I read. My goal is to gain more perspectives about our world and hopefully become a more thoughtful individual and citizen. How might you embrace this idea in your work?

What teachers might have heard is "Be like the principal who is modeling the right way to do something," or "My practice is not enough; I need to improve in how I create a more culturally responsive literacy experience." Maybe it's not what I said, but it could have been the message they received because I was presenting myself as an expert, bordering on arrogance.

Here is what I said instead to my faculty:

I recently read The Underground Railroad. I chose this book because I was reviewing what I had been reading recently on Goodreads, and I realized most of the authors were white. I realized how easy it is to get into ruts and that I needed to expand my perspective about the world.

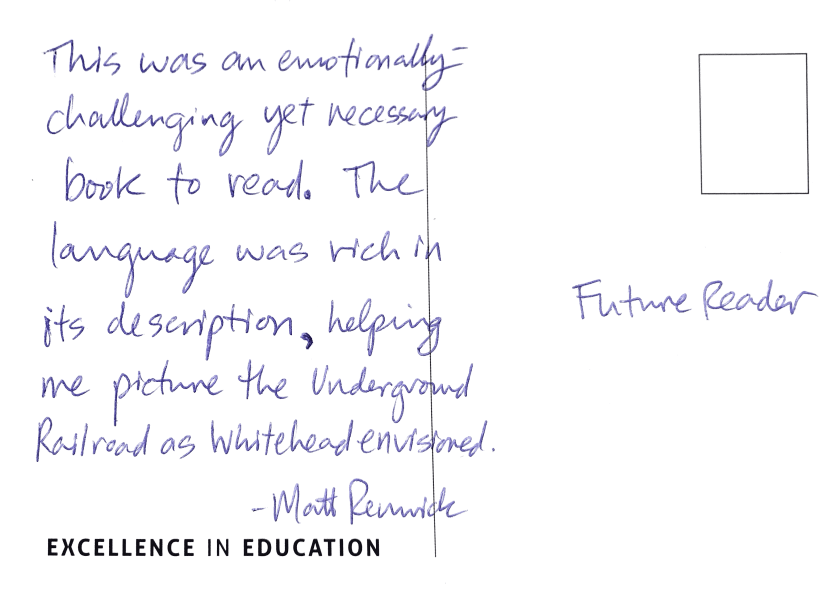

I also shared that I was contributing this title to the staff lending library and included a review ("Postcard to a Future Reader") that was inspired by the initial contribution from the other teacher.

Afterward, I handed out an article on culturally responsive instruction, acknowledging that this author understands and describes the concept a lot better than I can at the time. "Read it when you have a moment, and maybe we can discuss it at our next schoolwide professional development day."

I essentially communicated the same thing: We should be examining our practices through a more culturally responsive lens. The difference is in how I said it and how I presented myself: not one with the expertise but someone simply curious and has much to learn.

When I have encouraged other principals to bring some humility to their leadership, they often scoff at the suggestion. "Oh, I could never be vulnerable with my teachers. They will use it against me," I recall one administrator saying.

Being vulnerable and leading with humility is not looking incompetent or setting yourself up as a target. It's about being honest and public about our limitations as professionals and that we can always grow. This is the same attitude we want in our teachers because it is the first step toward building trust in each other. And if we can trust each other, we can learn from one another.