Two Simple Strategies for Teaching Today's Writers

Success and consistency may be more important than standards right now

Since the pandemic began, students have been writing less.

It almost seemed inevitable. When students were at home for remote learning, the environment was likely not as conducive for writing as school. They didn’t have as much access to the authentic accountability of conferences with teachers and peer feedback groups. Add increased screen time and all the distractions of the digital world, and the results are as one would expect: less competent and confident writers.

What’s the appropriate response? Some schools appear to be going forward, full steam ahead with meeting standards and doubling down on isolated skill instruction.

Unfortunately this perpetuates the very thing most educators hate about standardized assessments: they don’t measure what matters to students.

If students are not yet ready to meet grade level expectations, designing lessons with standards in mind first instead of the students in our classroom seems unwise. Instead, let’s meet them where they are at.

Two Simple Strategies for Supporting Successful Writers

“Everybody is a genius. But if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole life believing that it is stupid.”

- Albert Einstein

Rather than lower our expectations or ignore the standards, take the long view here. What is the best pathway I/we can create that will set learners up for success? What could a series of steps look like that will eventually lead them to become more confident and competent writers?

Before building out a new unit of study (and I am sure it will be wonderful, but hold off a bit), think about how we might rebuild our students’ writing habit. Two strategies - starting small and writing daily - can be just what they need today.

Starting Small

One of the best parts about writing small is that the writer feels a sense of accomplishment. They have written.

This is not some strategy you only see in schools. Roy Peter Clark, author of How to Write Short: Word Craft for Fast Times, notes that small doses of writing have been around for ages and can still be relevant in the 21st century.

“The demand for short writing is not an innovation. That need can be traced, through countless examples, back to the origins of writing itself. Here, for example, is a list, not exhaustive, of forms of shorting writing that users of the Internet have inherited in one way or another: prayers, epigrams, wisdom literature, epitaphs, short poetic forms (such as haiku, sonnet, couplet), language on monuments, letters, rules of thumb…” (pg. 7)

Here are some possibilities for writing small in school:

Tweets. Manage a classroom Twitter account. Summarize your learning and co-write posts with students that includes images (first getting families’ permission to post). Students can practice writing a tweet by providing them with half pages of 240 character spaces - the limit for Twitter posts.

Captions. After identifying and understanding how captions work in different texts, apply this knowledge by writing captions for images you take or the students bring in to school. This can become a group project by publishing a classroom book around a topic of interest that includes everyone’s captions.

Jokes. I tell a joke every day during morning announcements. Our budding comedians like to share their jokes with me during the school day. Some of their jokes could use some work…perfect for a writing conference. When ready, I let the students read their jokes over the public address system.

Blogs. For example, Seesaw offers a blogging tool within their portfolio platform. This might even a better option than Twitter as you can password protect kids’ posts so only families and classmates can see what’s posted. Plus, there is another opportunity for writing small by leaving comments.

Writing Daily

One consistent message from writing experts is: “write every day”. Journaling is a great place to start. If back in the classroom, I would see it as an easy way to start the school day, or as a transition activity when coming back from lunch. Or both! Fifteen minutes should be sufficient - “Don’t think; just write.”

Building this habit is not just devoting daily time for this practice; aligning journaling with its overall purpose and usefulness helps learners stay motivated and keep going.

For example, I would present journaling as a way of finding seeds for stories. “Some of what you write will have the potential to become a longer piece that you may want to take to publication.” To get some students started, consider co-creating an anchor chart with sentence beginnings such as these personal narrative prompts:

“I remember…”

“I don’t remember…”

“I’m trying to remember…”

“I’d rather not remember…”

“I forget…”

“I’ve been told…”

“What if…” (Source: Patti McNair)

The expectation could be that students have to select one journal entry per week to take at least to a final draft stage. This process forges a connection between journaling and publishing, in addition to the benefits of daily writing for simply practicing the craft.

Quotes can also be helpful for spurring writers. For example:

“What are the best things and the worst things in your life, and when are you going to get around to whispering or shouting them?”

― Ray Bradbury, Zen in the Art of Writing: Essays on Creativity

If all else fails and the student refuses to write, take Regie Routman’s advice and ask them: “Then what are you going to read?”

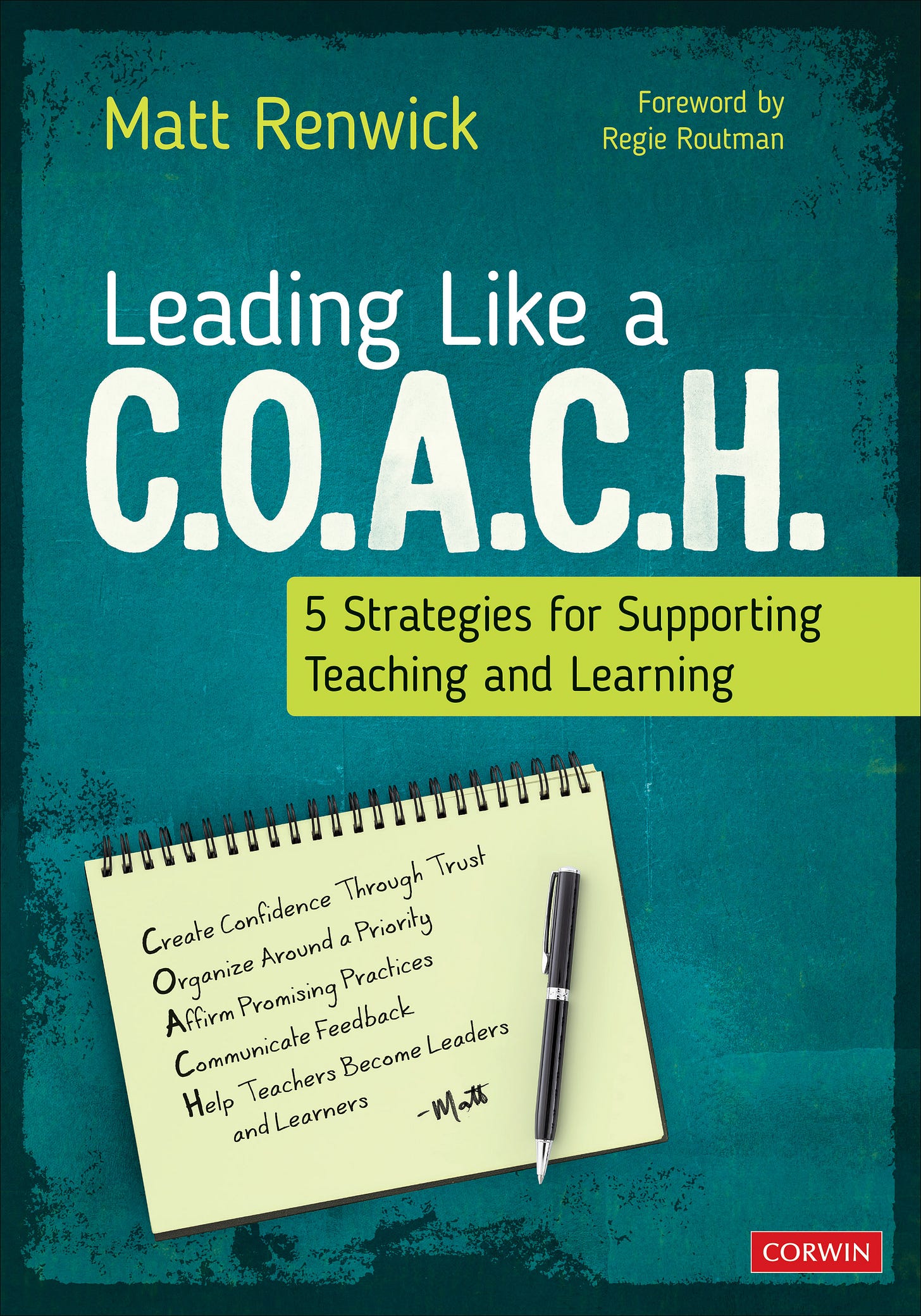

This year, like last year, has shown how much grace we need to give ourselves and others. Writing may be hard right now, but it does not have to be a chore. Creating confidence through short, daily writing seems like the surest and most enjoyable road to competence.

What do you find helpful for engaging writers today? Please share your strategies with this community.