Understanding Dyslexia: Research, policy, practice and public debate by Dr. Rachael Gabriel #wsra2020

Summary

When I saw that Dr. Rachael Gabriel was presenting at WSRA 2020, it reaffirmed why I return year after year to this excellent conference. Like Dr. Nell Duke last year, Gabriel offered necessary clarity on a timely topic that many of us have questions about. She is also the author of several book on literacy, including Making Teacher Evaluation Work: A Guide for Literacy Teachers and Leaders (Heinemann, 2017)

This session’s topic: dyslexia. How did we arrive at this point? What is research telling us? What are suggested next steps in ensuring all students receive an appropriate education? Next are my notes summarizing Dr. Gabriel’s session at the 2020 Wisconsin State Reading Association Conference.

How We Got to Now

The term “dyslexia” dates back to the 1800s. It translated to “word blindness” to describe those who could not read despite proper instruction.

This concept exists within the larger context of the history of public education supporting all students (or not) in the U.S. Gabriel walked the audience through a brief timeline of the goals of our institution to understand the journey we have taken up to this point.

1700s - Educational system constructed to teach only the top performers

1800s - Education available to more students, not compulsory or accessible for all

Early 1900s - Used a measure and sort approach to teaching different abilities

Mid 1900s - Started addressing group disparities (also birth of civil rights)

1990s - Response to Intervention introduced, learning disabilities recognized

2000s - Responding to source of difficulty, not just the disability in general

This last time period is in response to the different subtypes of dyslexia that we now know exist.

What Research is Telling Us

Orthographic mapping (sound + symbol for making meaning) has been around since the 2000s thanks to fMRI technology. There are “candidate genes” in the brain now identified that are likely correlated with a person having a form of dyslexia.

In response, programs and resources are becoming available that profess to address these needs. But because a study finds an intervention to be effective does not mean a program or practice should be adopted en masse, Gabriel notes.

Policy is often in place before we know how to address a student’s need in practice. There is not new legislation necessarily, but more replacing “reading difficulty” in state laws with “dyslexia”.

Also worth considering is the potential trade off in delivering highly specific interventions to a few students. For example, Reading Recovery has a long history of success for supporting struggling 1st grade readers. If schools adopt intervention programming that focuses only on dyslexia, do students lose access to other important elements of literacy instruction in the process? Gabriel worries about the same thing.

As we look to equalize supports, we risk alienating one group in favor of another. Lots of teacher training becomes focused on making sure we are using the product or program effectively.

She reminded everyone about the bigger picture by noting that secondary schools can “see the legacy of reading instruction in student behaviors,” not just one aspect of literacy.

Next Steps, Moving Forward

Understanding the research process and how groups and individuals utilize studies to support their positions will be important moving forward, Gabriel recommends.

The point of research is engaged conversation. It’s cyclical. We have to make generalizations to make sense of what we currently know and apply these ideas.

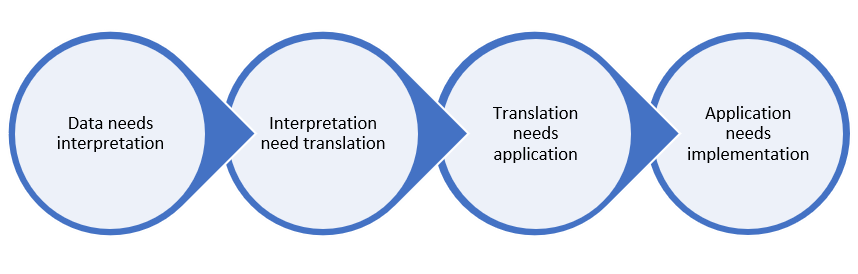

The speaker provided a helpful framework for understanding how information about reading instruction travels from raw data revealed from studies to the application and implementation stage in classrooms.

For the implementation/last phase, Gabriel added that it is “context-specific”, meaning that every classroom and teacher-student interaction is unique. Responses may vary.

So how do we know what’s true, for example if a program proports to be “research-based” when it in fact has no research to support its effectiveness? The speaker provided five ways for understanding what an individual or organization might profess and how to be more aware of their approach.

Unit of analysis & generalizations (a program or population was never studied, but many of its components were)

Sweeping generalizations (there are varied definitions of what an intervention means to “work”)

Language imprecision (we mean different things when we say the same thing, i.e. balanced literacy)

Certainty (authoritative discourses… “looks right, sounds right”)

Diversion (a counterargument is made without detailing the argument)

Gabriel offered a final point: research and science are not the only way we “know” things to be “true” or certain. At the same time, she recommended that every educator needs to keep an open mind to new ideas about how to teach readers.

If we believe we know everything about teaching reading, we are wrong.

Thanks for reading. This post was made public in the spirit of sharing and learning at the 2020 Wisconsin State Reading Association Conference. Subscribe today for future content on literacy and leadership in education.

Thank you for this post. I’m always nervous about how people approach education. There is a lot of charter BS in New Orleans where I live. The experiment here is done at the expense of poor Black and Brown students. I have a lot to add to this (LATER) if you are ever interested. This was one of my whole lives. Getting reading and spelling and writing instruction right, right from the start, has SO MANY societal benefits. The phrase “read or prison” is real. Check out the Reading League website/social media for more. Also Emily Hanford over on APM has several wonderful radio documentaries that really lay out the issue in a detailed but compelling overview. She and I are distant colleagues. I am also close with the Reading League. My son couldn’t read until I went through hell teaching him - by fault of schools and poor state level on down to city leadership - not to mention problems of curriculum choices by all...anyway.