Upgrading My Coaching Toolbox: Beyond Presuming Positive Intent

Newsletter

Whether it is a house project or our own coaching practice, we are most effective when we have the right tools for the contexts in which we work.

I recently experienced this in my attempts to repair the stone foundation around my house. My family and I live in a 100+ year-old home. The prior owner lovingly referred to the house as “a project” as we moved in. For the last four years, the mortar between the sandstone had been crumbling. After taking a class from a local mason on tuckpointing, I thought I could tackle this job with the tools I had.

However, I quickly learned the basic equipment I owned was no match for the stubborn pieces of mortar that were loose but unwilling to dislodge.

After connecting with a carpenter friend on this challenge, he offered to use his grinder. This handheld saw allowed me to burrow out the remaining mortar and then repair the seams between the stones.

Relating this personal anecdote to my professional coaching practice, I have been using the seven collaborative norms from Cognitive Coaching as the bedrock of my work.

Pausing

Paraphrasing

Posing questions

Putting ideas on the table

Providing data

Paying attention to self and others and

Presuming positive intentions

These coaching skills have been my foundation for productive interactions with clients. They have helped me support and empower educators to become self-directed in their practice.

When I shared this aspect of my coaching toolbox with members of the statewide coaching team, Joseph Kanke shared an article with me. “You might want to revisit the concept of presuming positive intentions,” he noted. “There’s some new thinking on the idea of presuming positive intentions.”

I’m glad I read it. Ruth Terry, the author of the article, points out that this “heuristic for navigating tricky interpersonal situations” can give others the benefit of the doubt. People mess up. They say insensitive things they could have phrased in a more productive way. They meant well.

Where presuming positive intent goes wrong, Terry notes, is that the benefit of the doubt seems to frequently be given to those in positions of authority. This authority may be positional - your boss, for example - or political, e.g. the loudest voice in the room. People who are in power too often exert it at the expense of those who are not, especially people from historically marginalized groups. Like a broken vase, the negative impact of their words or actions is still present after the event, like shards on the floor. People who didn’t create the mess in the first place are often the ones who clean it up, wanting to keep the peace.

Thinking about this article in the context of my coaching practice, I recalled situations where presuming positive intent was problematic.

The teachers who openly opposed a new teaching resource, concerned it would require them to enhance their instructional practice to better serve all students.

The administrator who authorizes remedial math courses that universities won’t accept for credit.

Community leaders who oppose affordable housing in our city, fearing it will introduce the challenges they associate with poverty.

With that, I decided to revisit presuming positive intent as one of the seven collaborative norms/coaching skills in my repertoire - I upgraded my toolbox to fit the job at hand.

After some brainstorming (and wanting to keep the all-important “p” alliteration), I came up with the replacement: Preparing the Conditions for Change.

This strategy primarily involves planning prior to coaching interactions. I have historically not devoted enough time to considering the context and preparing for conversations that lead to more equitable educational environments for students.

Next are my initial thoughts on how preparing the conditions for change will look like.

Be clear about the intention of the conversation or meeting.

Ensure inclusive language is prioritized from the start.

Provide clarity about what is and is not acceptable, i.e. working agreements.

Offer channels for surfacing questions and concerns in a safe way.

Provide parking lots and devote time to address what is posted.

Give time for individuals to process their thinking through writing and small group discussion before coming back together as a whole group.

When something unproductive is said or done, have coaching intentions ready with the intent to disrupt without disrespecting.

Start with curiosity. If a comment is made that feels insensitive, ask them, “Can you say more about that?”. Give them an opportunity to clarify.

Get specific to avoid stereotyping. As an example, when an educator laments that “these families just don’t care”, I could inquire with: “Which families don’t care? What have you personally observed?”.

State your position on the issue to expand people’s perspectives. Continuing from the previous example, I might say: “May I share a different perspective? I think these families do care, they may just use different avenues to demonstrate it. For example. . . “

Will there still be moments when I presume positive intent? Certainly. People make genuine mistakes—that’s how we learn. However, the key lies in being aware of each person’s positional power within the contexts we navigate. As facilitators of professional learning, our role is to empower everyone to have their voices heard. Preparing the conditions for change offers a more nuanced approach than relying on basic assumptions in complex situations. By intentionally upgrading my toolbox, I aim to create spaces where equity is not only a goal but a way of being.

Related resources

This article was also posted in Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction’s Coaching Chronicles newsletter. You can access it here. The Coaching Chronicles is an excellent quarterly newsletter, written by coaches working in K-12 schools. Subscribe here.

You can access the Ruth Terry article in a previous post I wrote about facilitating literacy conversations that move a school culture forward. It offers strategies for managing the uncomfortableness of growth and change. I pointed out that keeping the peace “is really the status quo. It’s the way we have always done things. And that is why schools are getting the results they see. Allowing for things to remain the same means we accept less than excellence, that we are comfortable with some students not being as successful as they could be. All in the name of avoiding some personal discomfort.”

I still lean on Costa’s and Garmston’s collaborative norms as coaching tools. For a Reader’s Digest version of their voluminous Cognitive Coaching, check out Cognitive Capital: Investing in Teacher Quality (with Diane Zimmerman).

Premium Post

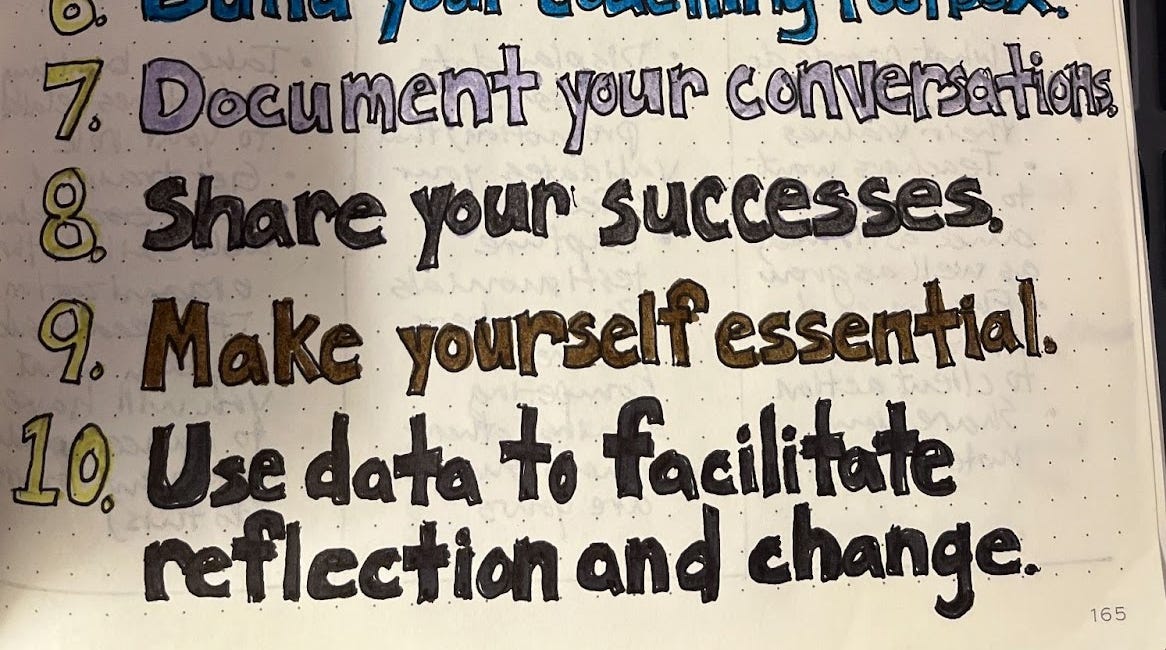

Yesterday, I shared ten steps a coach can take to becoming more confident in their role. You can access it below with a paid subscription.

Becoming a Confident Coach: Ten Steps to Feeling and Being Successful

A year and a half into my role as a systems coach, I recently took some time to take a step back and examine my work.