When Less is More

Article

Have you reduced expectations for teaching since going to remote learning?

Maybe, and probably not enough.

It’s hard to admit this. We pride ourselves as educators on guiding students to reach their potential. We prepare explicit instruction for classroom or professional learning. We rely on visible results of learners’ responses to celebrate what went well and make adjustments for what did not.

There is no “we” now, at least in the physical sense. Now, our support is at the mercy of our imperfect technologies. What we might perceive as explicit is too often unclear in the eyes of our learners. The response to our instruction might be nothing at all, even if it did make an impact on learning.

Readjusting Expectations

I’ve seen many articles online offering ideas for successful shifting to remote instruction (include one of my own). How many have called for lowering the bar?

This makes sense. Educators are on a steep learning curve with technology. It’s been layered over the already challenging task of instruction.

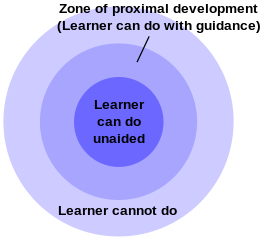

Consider Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development. The theory suggests we learn best when the level of challenge is within our current capabilities. Not too challenging, not too easy - the sweet spot for learning.

Nothing feels easy right now. It’s one reason why people feel exhausted. We are expending enormous amounts of mental and emotional energy just maintaining our connections and sustaining our communities. Small tasks we likely took for granted pre-pandemic now involve many steps.

Consider the following additional steps for conferring with readers:

Learning how to use a video conference tool.

Setting up a video conference appointment.

Transferring that appointment to our digital calendar.

Inviting students to the appointment via email.

Hoping that the students shows up for the appointment.

In the past, all a teacher had to do when they wanted to confer was to grab their notebook, a pen, and sit down with the student.

Reducing Instruction

In a blog post for Stenhouse Publishers, Reducing Instruction, Increasing Engagement, Peter Johnston wrote about the paradox of minimizing teaching to maximize student achievement. He and his colleague Dr. Gay Ivey studied middle level classrooms that kept instruction brief while creating more time for students to read books they wanted to read and talk about what they were reading with peers.

Everything they measured increased, beyond only student motivation: number of books read, attendance, positive feelings about school and themselves, even test scores. As Johnston shared the results of his study, he asked some pertinent questions:

What does it mean that students learned more with about half as much in-front-of-the-class teaching (which students could ignore if they were engaged in a book)? How should we weigh these changes in student development relative to achievement on state tests? How should we think about the absence of these achievements from the Common Core Standards? What does it mean when apparently reducing instruction but focusing on engagement actually increases the breadth and depth of achievement?

A Strategy: Running Progress Reports

Even if our capacity for instruction is limited, student learning can still flourish. The challenge comes in shifting our roles from the role of teacher to online facilitator.

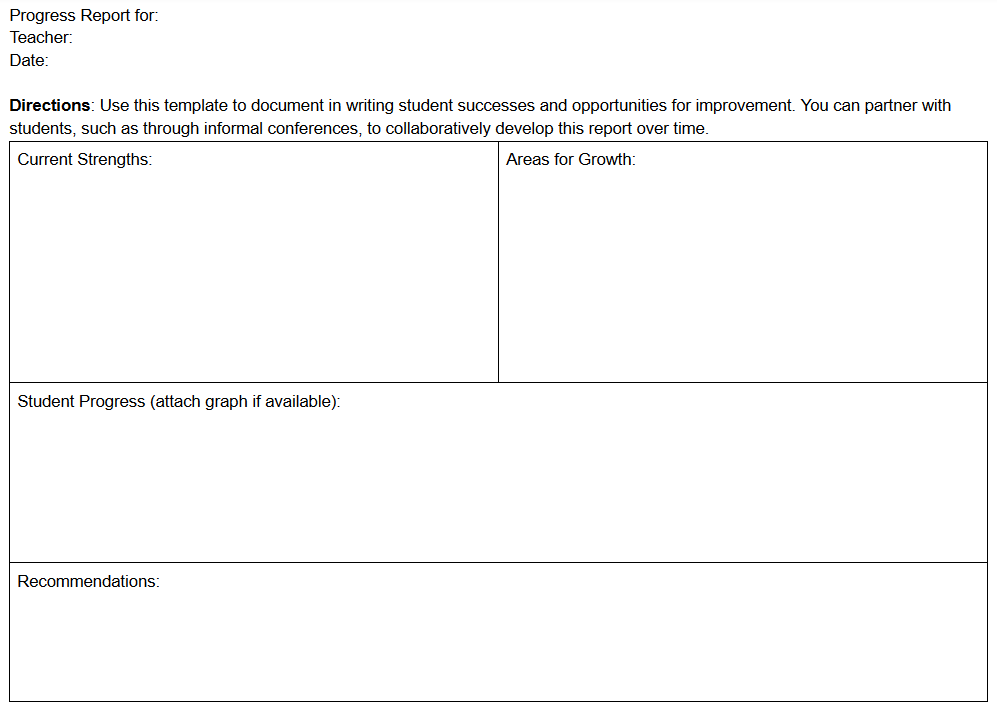

For example, if students participate in online book clubs via Zoom or Google Hangout, a teacher can sit in and listen while taking notes using a form such as the one below.

This “running progress report” can replace end-of-the-year report cards and kept as a constantly updated Google Doc. One can be maintained for each student. If instruction is reduced, it frees up the teacher to be an observer of learning online.

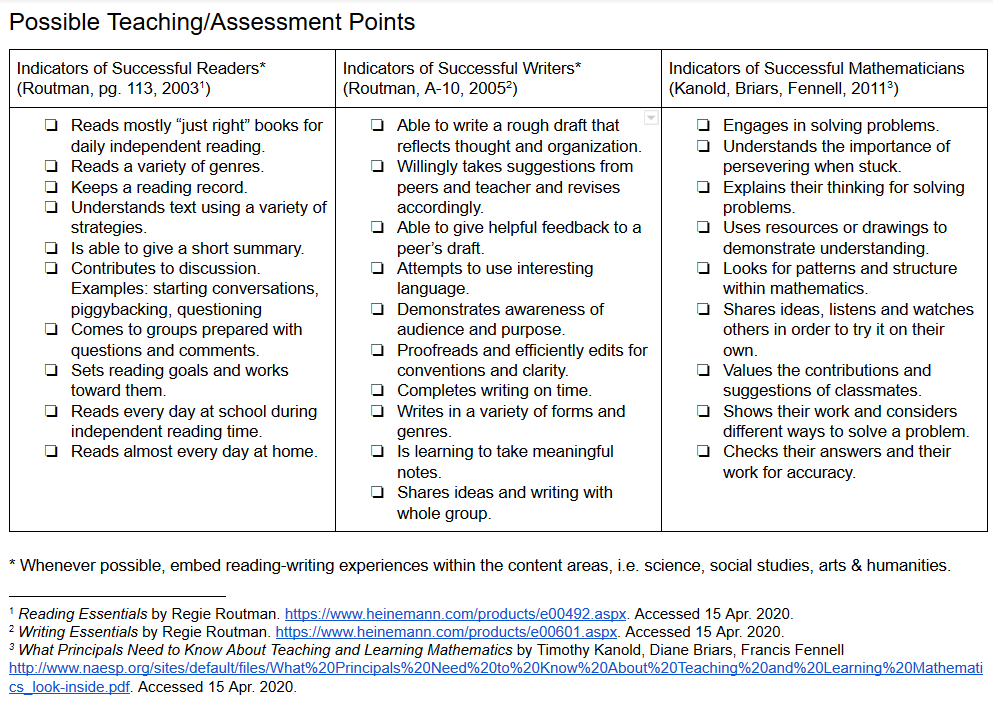

Older students can be asked to co-develop this assessment tool with the teacher. For younger students, the teacher would be the primary curator but could still include the student in the process of development. Checklists such as the one below are helpful addendums for guiding observations and discussions around student progress.

(Click here to make a copy of the Google Doc version of this template.)

Whether online or in person, responsive instruction often means less is more. Less preparing elaborate lesson plans, more thinking about students’ interests and needs. Less paper copies, more professional knowledge needed. Going to remote learning has accelerated the need to shift toward a more minimalist approach to teaching students.

This article would typically be for subscribers only. For the month of April, all content is available for free due to the hardships brought on by the pandemic.