Writers Workshop Mini-Lesson: How to Deal with Deadlines

Article

This week, I was graciously invited to lead a writers workshop mini-lesson in 5th grade. The classroom teacher shared a source of tension in the classroom: some of the students were experiencing stress with how to deal with writing deadlines.

Why deadlines? Was there a specific challenge for certain students? For example, did they not have enough time to write? Or, did they not have the tools and strategies to manage their time effectively?

Considering this information, for this mini-lesson, I wanted to accomplish two things:

Rethink how time is utilized within the writers workshop framework.

Provide all students with common ideas for structuring their time and writing ideas.

(Click here to review my prepared mini-lesson. This is a modified template found all over the Internet so I wasn’t sure who to attribute it to.)

Combining The Workshop Framework with the Optimal Learning Model

Both of these instructional frameworks have a similar goal in mind: student independence. We support our students to become independent through clear instruction that includes students in the teaching-learning process. We release the responsibility when students are ready, not too soon while not waiting too long either. The following visual is an integration of the workshop framework by Samantha Bennett and Cris Tovani (Tovani, 2011) and the Optimal Learning Model by Regie Routman (2018).

What teachers and learners both need is structure. Each framework offers this, helping us organize our thinking and our predictions about how instruction might go. It’s an educated guess that gives us some peace of mind.

And that’s what I also wanted to provide students: structures in which to put their ideas and plans down so they can focus more on the writing and less on getting it done. We strive to make sense of our worlds when creating something new.

The following is a summary of how the lesson went along with commentary afterward.

Starting the Lesson (“I do it.”)

“Before we begin, tell me about your concerns regarding deadlines and writing.” The students look at each other, smiling sheepishly, not sure how to respond. “Really!” I affirmed. "I’m interested.” I held a small notebook and a pen in my hands, ready to take down their feedback. Slowly, they revealed their anxieties about due dates.

“I don’t like having to work on my stories at home."

“It’s hard to write when there are distractions."

“Sometimes we are talking and not focused on our work."

“My story is too long."

Instead of judging their responses, such as saying “Talking is important for writing.”, I wrote down what each student said in my notebook. I wanted to show I was listening. My notes would also serve as an assessment point, information to come back to at the end of the lesson to see if we were successful.

Next, I explained the two strategies we would be learning to better manage writing deadlines: the “Five Whys” strategy and creating sprints.

“I assume a lot of you are familiar with the car company Toyota?” Several nods and hands raised. “Great! They developed this protocol to use when they were stuck in a problem.” I wrote, Why? five times on the board. “I am going to share with you how I used this process to help me with some writing challenges I recently experienced.” I shared my thinking while writing a recent article on the board.

“Who would like to try this with me as a shared demonstration?” A student came up and shared that her story was about foster children. While I asked “Why?”, she would respond and I would write. We discovered that her purpose was actually to write humorous fiction.

Now that students had observed two examples, I asked them to try it out on their own.

After a few minutes, I noticed that some students hadn’t started. Maybe they are still thinking about which writing to analyze, or they simply need more support, I thought. Instead of another teacher-led demonstration, I paired them up with a classmate and they interviewed each other, just as I had modeled previously.

Guided Writing Time (“We do it.”)

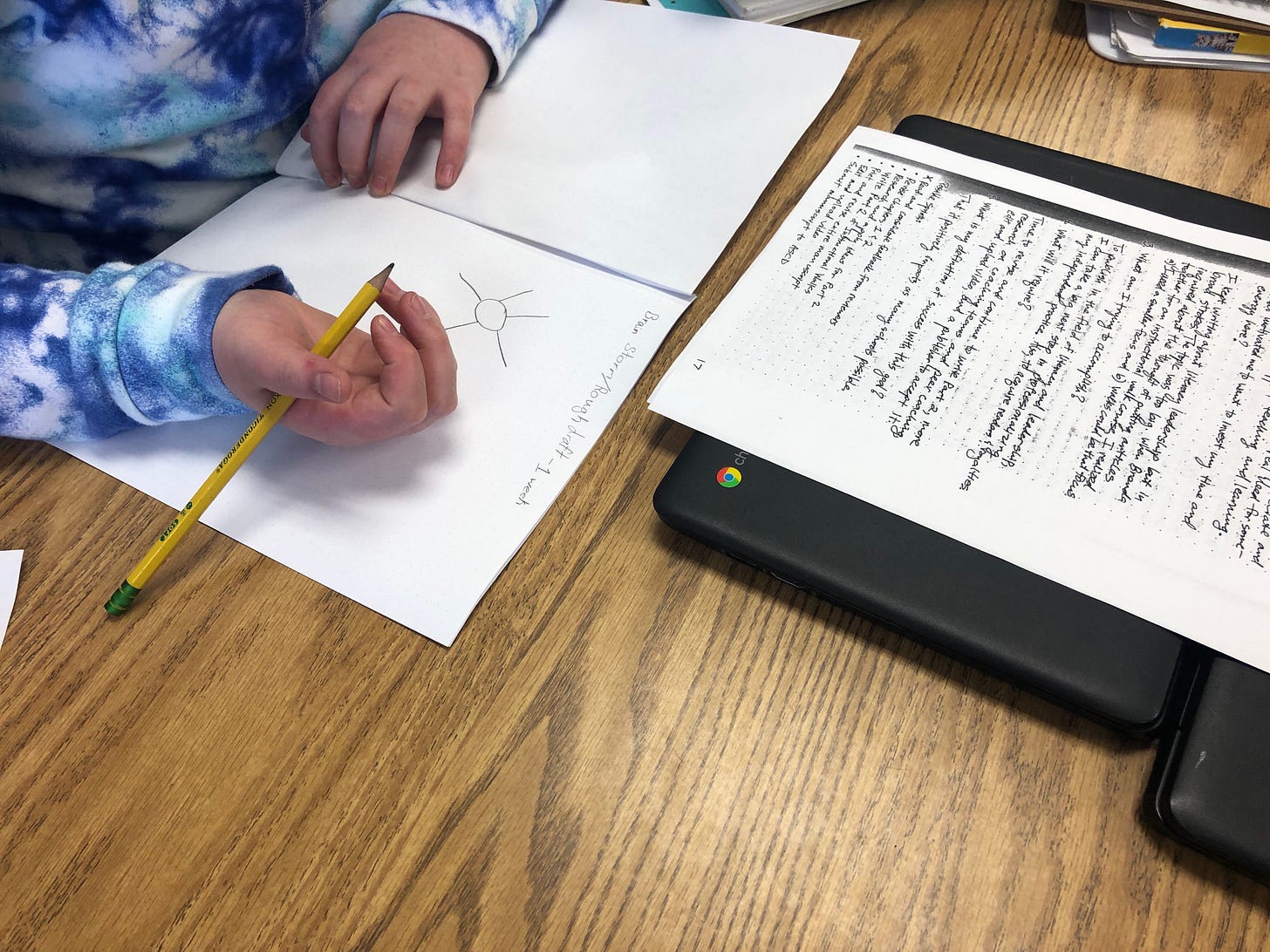

“Okay, stay in your pairs. Now we are handing out resources for the second strategy: sprints.” I had made copies of my journal notes from a current writing project I am working on, along with a blank journal for each of them.

I briefly explained how I was taught by an editor to break down large writing projects into chunks. “These short projects are called ’sprints’. Think of them as small tasks that you can accomplish in a reasonable amount of time. They help you feel like you are making progress and focus on what’s important.” Together we looked at my example, noting the number of days I felt I needed to accomplish each sprint.

Time was provided to discuss what went into their dot journals. Their teacher had already taught them how to make character webs and other graphic organizers to help organize their ideas. “All of these strategies are great. There’s no wrong way to use this tool. The important thing is you feel like you have a handle on your project and are less stressed about getting it done.” I did briefly model a favorite mini-strategy within a dot journal: affirmation lists.

The student pairs were released to try this together. The other adults in the room and I roved around the classroom, supporting students as needed and asking questions.

One student had listed “five days” as the amount of time she needed to develop the first draft. “Are you struggling with this piece of writing?” I asked her. I didn’t want to outright say, “Five days is too long,” as that would be an assumption.

She shared that this writing was going well already. “It sounds like you are experiencing flow in your writing. Good for you! Do you think you could do it in less than five days then?” She smiled and nodded. My theory, that she was nervous about even setting a deadline, was likely confirmed.

Independent Writing Time (“You do it.”)

“Everyone, can I have your attention please, just briefly?” I was holding up one of the student’s dot journal pages for all to see. I had found my “link” lesson that would hopefully transition the class to independent writing time.

“Notice how she used her journal page. She drew a character map to help flesh out this person in her story. Like the affirmation list I created, this helps Emily as a writer. Make the journals to be what you need. It’s your space to be messy and make mistakes. I know how hard it can be to look at a blank document on a computer screen when getting started.”

Students then wrote independently for the next fifteen minutes. It wasn’t the planned amount of time that I wanted (25-30 minutes). But as another teacher pointed out, we respond to our students’ needs, not a lesson plan. They needed more time at the shared demonstration/“we do it” phase based on the informal feedback I was getting while teaching.

As the students were writing independently, the other teacher and I discussed how the ideas from this one mini-lesson could be carried over the next two to three days. “We could keep coming back to the strategies and discuss at the beginning and end of writers workshop.” In their journals, I had also included writing tips developed by Regie Routman.

At the end of the lesson, I pulled back students to celebrate and review our work. Students offered several accomplishments.

“The tsunami ending I had was too short and weird, but today I was able to extend it. Now it makes sense."

“Comparing my last writing to today’s, I had better descriptions."

“I found a grammar checking tool to help me with my edits."

I also came back to their initial list of worries about deadlines. “Give me a thumbs up, down, or sideways on how well this lesson addressed each concern.” I marked each one with a plus (yet) or minus (not yet) based on their feedback. The “not yet” could be topics for future mini-lessons, either small or whole group.

Reflecting on the Writers Workshop Lesson

In this reflection, I want to address two areas: To determine if I accomplished what I set out to do, and to examine the workshop model from a broader perspective.

Part 1: Time and Common Instruction

Regarding time as a challenge for both teachers and students, we are only provided so much of it. That goes for a lesson, a unit of study, a school year. When one shares concerns that “I don’t have enough time” or “I don’t like deadlines”, what can really be done? Maybe change the schedule, but that’s often only reshuffling the deck with the same set of cards. So instead, I focused on getting the students involved in the lesson as soon as possible, at the first indications that they were ready for the responsibility. Time was now on the students’ side because I chose it to be.

As mentioned previously, after the lesson I felt a little guilty that we spent more time on the modeling and shared demonstration than planned. However, this is what the students needed. We also discussed how this one mini-lesson could carry the kids for the next couple of days. Subsequent lessons could merely touch on what was already learned or answer any questions. So overall time was utilized fairly well.

In their book Schools That Work: Where All Children Read and Write, Richard Allington and Patricia Cunningham reinforce this point (p. 146).

“Time matters, but how time is used matters more. Setting aside large blocks of uninterrupted time or extending the school day or year are good beginnings, but only beginning steps.”

Regarding my assumption that all kids can benefit from common lessons, I continue with this theme of time. We can devote an inordinate amount of our valuable preparation time to designing lessons that are differentiated for every kids’ learning style and preference. I did not have that luxury. So I instead focused on creating the most engaging lesson I knew how to do. Did a few kids have these skills already? Possibly. Did a few kids not yet get it? Probably. Yet through shared demonstration, we have also added to our common language in the classroom. If I were to continue teaching during this block, I could more effectively utilize formative assessment notes and respond to those students appropriately during guided and independent work time. We are speaking the same language.

Of course, this type of response relies on my capacity as a knowledgeable and responsive teacher. It means I need to be an avid learner myself, exploring current educational ideas and keeping up on the latest research about what works best for our students. It also means knowing my students well, as individuals and as learners. What it does not mean is that I have to read every piece of literature in the classroom library or to set up the perfect guided reading lessons. Know my students and know literacy. This leads to some general comments about the workshop model itself.

Part 2: Revisiting the Workshop Framework for Instruction

At a reading conference I recently attended, Dr. Nell Duke brought up an interesting research finding: The workshop model has an effect size of 0.34. The “hinge point”, as Dr. John Hattie describes for practices that can lead to at least one year’s worth of student growth within one year of school, is 0.4. So 0.34 is “good but not great,” noted Duke. She also shared that for students with special needs, the workshop model has no significant effect on their learning. (The study Dr. Duke referenced can be found here.)

This recent understanding led me back to my own teaching days in a grade 5/6 multi-age classroom. I remember peeking into my counterpart's classroom from time to time. He used the workshop model. Often he was conferring with kids while others were reading or writing. But were they learning? I wondered, with some insecurity in my questioning. My approach was much more structured, doing lots of modeling and then expecting students to “do as I do”. I did not include many shared experiences which I realize now is crucial for supporting and scaffolding student learning.

Thinking about my own experiences plus what research is telling us about the workshop model, I have arrived at a few tentative conclusions.

First, teachers need some type of structure to facilitate an effective literacy lesson. Frameworks can provide that structure. The challenge is in how scripted or loose we want to be with each lesson. It really depends on what we are teaching and what the students need. For example, if the lesson is more technical and skill-based, such as how to chunk our writing projects, then I want my plans tighter. If the lesson is more complex, such as discussing theme which can have many possibilities, then plans should be more flexible to allow for this.

Second, frameworks can co-exist. My marrying of the workshop model and the Optimal Learning Model seemed to work well. The key to this integration is that frameworks must have similar goals. In this case, the workshop model and OLM have the common goal of student independence. This is important when a school might have one building-wide approach while we are trying to align our practices and philosophy to achieve some semblance of coherence.

Third, many of the professional resources available to educators tend to lean toward more structure. For example, workshop resources offer teacher scripts and pre-designed lesson plans. But does this reduce teacher flexibility? They can if we treat these programs like the curriculum instead of the resource that they are.

Fourth, teachers appreciate these resources initially. They are especially helpful for new teachers and those new to the workshop framework. When they achieve a level of expertise, however, they start looking for more. Other thought leaders have confirmed this. The theory is teachers eventually realize that no resource, as good as it might be, can offer everything their students need. If teachers do not have an internal sense of quality that comes from a formed and informed philosophy about literacy instruction, they end up scouring the Internet for that next great lesson or resource.

This is why we have taken the approach in our school to build teachers’ shared beliefs about literacy. Combined with the Optimal Learning Model, we have invested in everyone’s capacity. Then when teachers realize the resource they have invested in is not always meeting their kids’ needs, they have a wealth of knowledge to rely on or they know where to look for more guidance. This is how I ended up leading the lesson depicted today: the teacher wanted to see a different way to teach writers workshop.

It wasn’t perfect. But the imperfections of my instruction are also what made it helpful for the teacher: it was affirming. We don’t see this enough in education. We instead purchase products that show up in colorful glossy packages and describe what to do and how to do it best. If we deviate from the script and we don’t see ourselves as an equal authority on instruction, we might feel less confident about our capacity as a teacher. The reality of the classroom is messy and unpredictable. It doesn’t help when the same subtle message about “best practices” is communicated by a principal, such as when they remind faculty to ensure they are teaching with fidelity to the program (instead of responding to their students).

How do we gain this sense of authority? By being seeking out what we may not know while remaining true to our core values. By trusting others and having the confidence to put ourselves out there, such as through asking critical questions. This attitude is developed through intentional choices, best cultivated within a school culture that encourages risk-taking and innovation. It leads to a lifetime of reflective learning. By prioritizing our time and attention to what matters through informed beliefs and an effective framework for instruction, we start to develop the confidence necessary to choose what content and which strategies to present in our classrooms.

References

Allington, R. L., & Cunningham, P. M. (2006). Schools That Work: Where All Children Read and Write, 3rd Ed. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Routman, R. (2018). Literacy Essentials: Engagement, Excellence, and Equity for All Students. Portsmouth, NH: Stenhouse.

Tovani, C. (2011). So What Do They Really Know?: Assessment That Informs Teaching and Learning. Portsmouth, NH: Stenhouse.