For Writers Only

Including Five Ideas for Creating a Safe Writing Space for Students

“Failure is not an end - it is the means to an end. Study your failures, for they are the scrambled secrets of success.”

― Romina Russell

I had one month left to complete my edits for a forthcoming book. What I know about myself as a writer is that once I get going, I enjoy the process. It is the getting started part of writing that is the hardest.

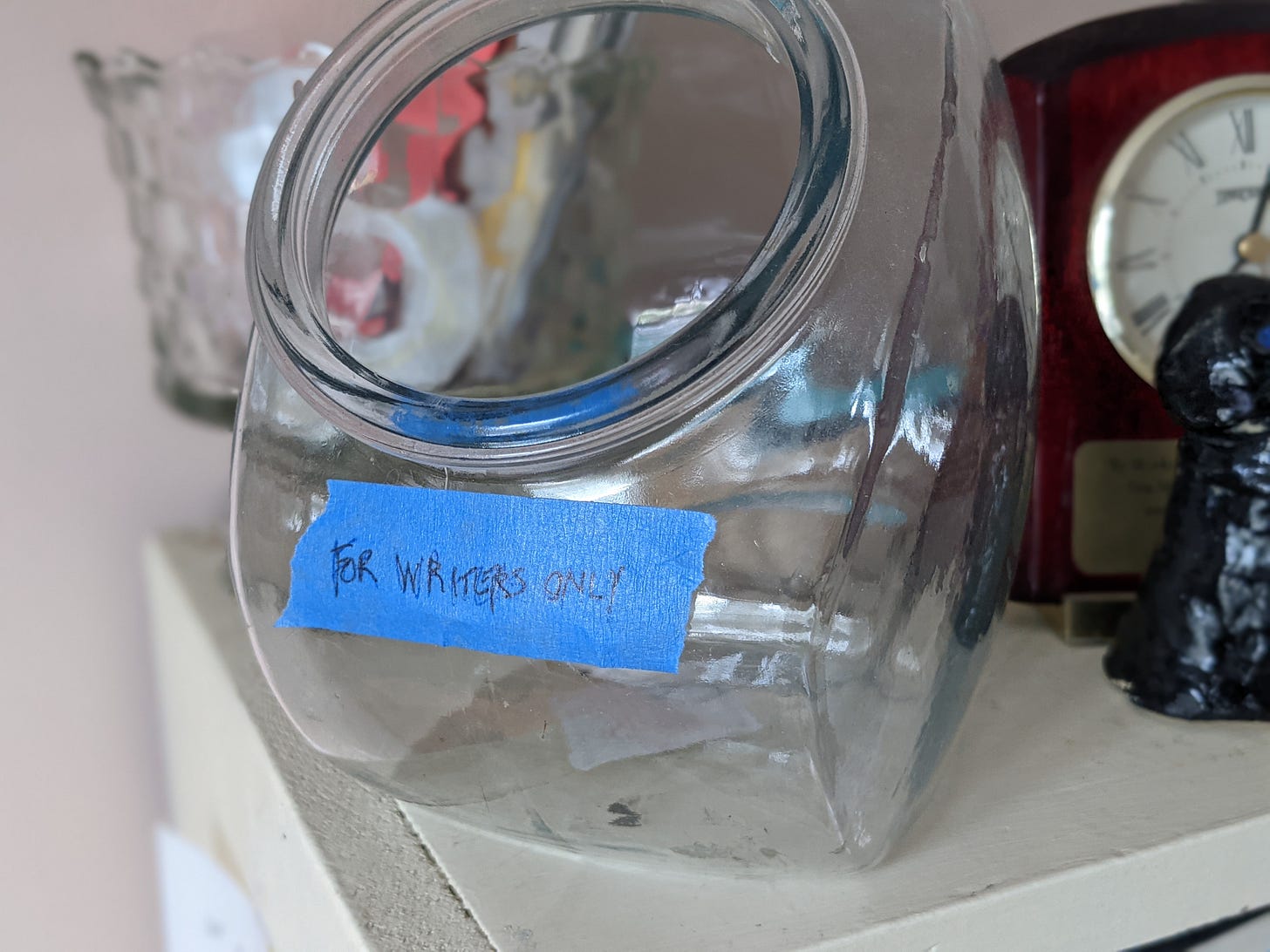

I am not above hacks, so I bought a bagful of Dum-Dum suckers and put them in an empty candy jar on top of a bookcase. The plan was, I would get a sucker if I sat down, opened my laptop, and get to work. Essentially, I was rewarding myself for getting started.

Once the suckers were in the jar, I remembered that I have two kids who have inherited my sweet tooth. Instead of wasting time monitoring how many suckers I had left or telling my two adolescent children not to do something, I wrote on a piece of masking tape “For Writers Only” and stuck it just beneath the candy jar opening.

It was a good reminder for me, but it seemed to be a terrible limit for my kids. There’s no way I am eating that many Dum-Dums, I told myself when I noticed the jar was half-empty one day. The progress of my rewrites did not match the progressive disappearance of the suckers.

Why is writing so difficult at times? A few reasons:

It is work and requires concentration.

I may not have any ideas to write about and need to do some reading, research, or living.

Yet the biggest reason may be a fear of judgment. Even if we have no intention of publishing a piece, by writing something down we have now made that a possibility. This fear leads to a desire to get the writing “right” (whatever that is). We put unhealthy expectations to create something good, and then we spend too much time thinking about what that something good will be instead of just writing.

“Nothing Profound”

I experienced this timidity at a writing retreat a couple months ago. A writing teacher at the University of Chicago, Patty McNair, was leading a workshop, helping us to mine our own stories. When my turn came up to read what I had drafted to the group, I prefaced it by sharing that it is “nothing profound”.

The teacher grinned and responded, “I hope not. Otherwise, it would probably be terrible.” The whole group laughed, not at my expense but at the familiarity with this truth. When we put unrealistic expectations on ourselves to write a viral story or a best seller, anything less than that is a disappointment. Worse, we might identify with that disappointment as a part of our self.

How do we balance reasonable expectations for success with the acceptance that we are bound to fail? Author Bill Kenower1 understands this success/failure paradox as part of a more holistic writing practice.

“You cannot have a coin with only one side, and you cannot have success without failure. Our fear of failure begins when we decided to become authors. The sharing of work with others, the clearly delineated linguistic difference between an acceptance and rejection, and the irrefutable, quantifiable difference between being ranked number one in your genre on Amazon and being ranked 1,245 can distract us from what writing has already taught us about opportunity and suffering” (pg. 190).

Educator Thomas Newkirk2 offers a similar explanation for how writers walk a thin line between healthy and unrealistic expectations.

“When we see teachers reading our work generously, we have a model to internalize, so that we can be generous toward ourselves. Not that we become complacent or protective of every precious word, but that we can be kind toward ourselves. We can accept ourselves, take pleasure in our work, and not succumb to the trap of being hypercritical” (pg. 96).

What both Bill Kenower and Thomas Newkirk explain here is what I think McNair was trying to get at when I prefaced my reading with a self-deprecating statement: Aim to write and be a little less attached to the outcomes.

A Found Wrapper

My book was close to done and I had good momentum, so I did not see the need to refill the candy jar. After one rewriting session, I came down to the kitchen to make myself lunch. My son happened to walk by; a sucker wrapper fell out of his pocket.

I picked it up, held it out and asked with a half-smile, “So what have you been writing?” My son matched my grin and sheepishly responded, “Lore.” I paused and then asked, “What is ‘lore’?” He explained that he has been entering an online drawing contest once a month. The superheroes he creates in his sketchbook or tablet must have a backstory associated with them. “Nice! If you want to me to take a look at any of your creations, let me know.” He mumbled “well, maybe” and went back to his drawing.

I have yet to read any of his backstories. But he’s writing. Maybe the suckers and the “For Writers Only” message were helpful for him to feel safe to take a risk. We writers have to look out for each other.

Five Strategies for Creating a Safe Space for Writing

Craft community norms with students. One of them can recognize that importance of mistake-making as a pathway toward competency.

Design your classroom environment in a way that invites students to write. For example, devote a couple of desks or tables with chairs “for writers only”. Provide paper, various writing/coloring utensils, and a stapler for kids to make books or craft articles. A laptop or tablet could be available for students to post their work in a digital portfolio or learning management system.

Offer simple strategies to help students get started in their writing (beyond a candy jar :-). Patty McNair gave us an excellent idea: put “~ See it ~ Feel it ~ Hear it ~ Taste it ~ Smell it ~” at the top of the page in which we intend to write a first draft. It is a reminder to provide rich description for the reader, which is almost always a smart writing move.

To help writers feel a sense of accomplishment and know when to stop writing, Bill Kenower recommends these two questions: “What do I want to say?” and “Have I said it?” If they can answer these two questions, then it is time for revisions if the intent is to take it to publication.

During peer revisions, ensure there are more affirmations than critiques when kids offer feedback to each other. This will help with what Thomas Newkirk describes as “self-generosity” as they consider any feedback for improvement.

Kenower, W. (2017). Fearless Writing: How to Create Boldly and Write with Confidence. Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books.

Newkirk, T. (2017). Embarrassment: And the Emotional Underlife of Learning. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.