How teaching reading but not readers leads to ineffective instruction for all students

Newsletter

This past week, I read three unique and distinct texts.

Directions for installing a ceiling fan. My son and I replaced his light and fan once it stopped working. I read the first couple of pages of the directions before getting started. Knowing what tools I would need for the entire process meant I wouldn’t have to keep going to garage to find what I needed to complete the project. Related, reviewing the inventory of parts and comparing it with what came in the box helped ensure nothing was missing.

An online article about artificial intelligence (AI). Ted Gioia has an excellent newsletter on music and culture. For the article I read about AI, I considered posting a comment. To do this I needed to know how to create an account with Substack (I already have one).

House of Leaves by Mark S. Danielewski. This novel crosses many genres: horror, fantasy, mystery, thriller. It’s also written in a style I have not seen before: one author writing about another author writing about a family whose house is bigger on the inside than on the outside. There are footnotes, and then there are footnotes for the footnotes. Some of the commentary goes on for pages. You aren’t sure at first which story to prioritize as you read.

What do all these texts have in common?

First, the unique skills I needed to read these texts were not taught in school. To be fair, blogs and other online forums for commentary were not ubiquitous when I was enrolled in public education. However, knowing how to read footnotes and endnotes is a general expectation for academic work. Regarding the ceiling fan directions, I took two years of shop classes! It seemed like a missed opportunity to integrate literacy and technology.

Second, the background knowledge I needed to engage with these texts came from previous self-selected reading and past experiences. With the ceiling fan, my guess is I learned to read directions from the school of hard knocks. As for understanding the steps to participate in online discourse, I have read and written many blog posts of my own choosing since becoming an educator. My penchant for texts like House of Leaves was started in adolescence, scouring the public library shelves for Stephen King, Ray Bradbury, and related authors.

Finally, I chose to read these texts. I do remember having a lot of latitude in what I chose to read in my youth. Yet I wonder: what was my decision-making process? Clearly, I needed to replace the ceiling fan. But how did I come to subscribe to Ted Gioia or the horror genre? This thinking behind my thinking was never surfaced growing up.

So, what does this all mean?

An initial thought: literacy curriculum resources that aim to address all students’ needs may end up supporting none of them. Commercial programs are typically developed by selecting the most common skills and knowledge bases. These are determined by state standards and the state exams that test students for proficiency in these areas. The skills and knowledge spiral throughout the program, grade by grade and sometimes within the same year.

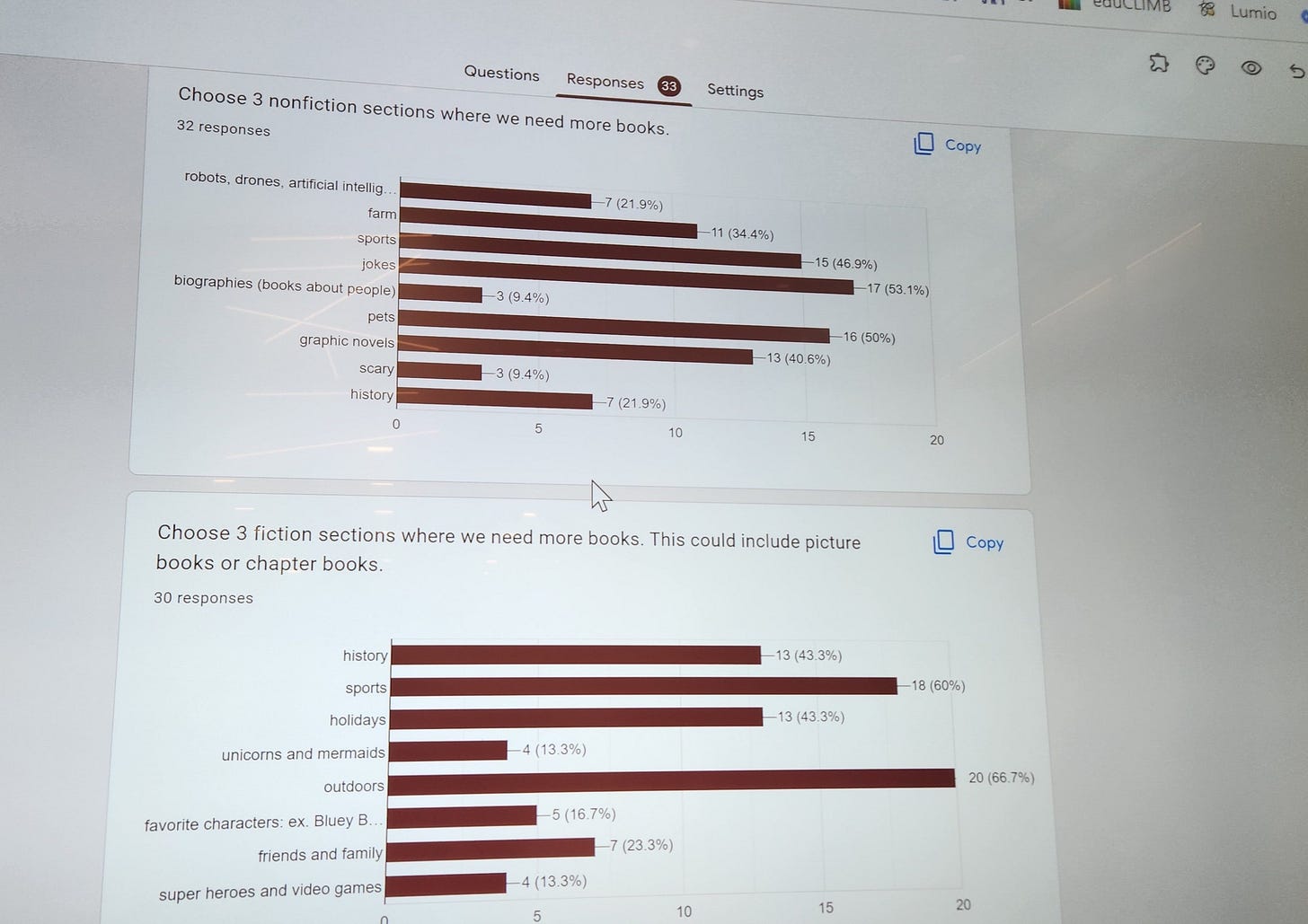

Conversely, this excludes a lot of niche competencies and high-interest topics that kids crave. Professional sports, haunted dolls/houses/landmarks, and technical guides were some of the most common requests when students were allowed to select new titles in last year’s school library book budget project.

I am reminded of the story of the Air Force designing cockpits for fighter jets for the “average pilot”. The theory was that an average size cockpit, based on ten different body measurements, would fit most pilots. Gilbert Daniels, an Air Force researcher, studied 4000 pilots. He discovered that not one pilot – zero – could actually fit into the cockpit.

As Todd Rose points out in his retelling of this story:

“When you design a cockpit on average, you literally design it for nobody.”

The same could be said for our commercial literacy programs. They are designed to align with standards; the term “standard” is defined as “used or accepted as normal or average” (my emphasis).

I am not proposing we throw out our curriculum resources. I would be a hypocrite if I did. The school I led just last year adopted a K-5 program. I believe a high-quality resource can help raise expectations, diversify the types of texts kids are exposed to, and create instructional coherence.

The key term in that last sentence is “help”. Curriculum resources can be a piece of the puzzle when striving to achieve schoolwide literacy excellence. But if treated as the end instead of a means to an end – independent, engaged, lifelong readers – they can become tools for limiting and even excluding students from their right to become a literate individual.

Considering all of this, where does one begin?

Heeding the lessons from the Air Force anecdote in Todd Rose’s TED Talk, educators can start by banning the average. In the context of a literacy curriculum program, that would mean treating the teacher’s manual as a guide and not a script. The first step in preparing instruction would not be to simply to turn to the next day’s lesson; the first step would be thinking about how each student responded to the previous lesson and adjusting accordingly.

This leads to designing instruction to the edges. For example, optimize choice in what to read and provide access to high-interest texts at varied readability. Ensure there is time every day for students to read independently. Provide support as needed in this context, e.g. conferring, partner reading. The core passages and activities in the common resource are treated as opportunities to practice for the real reading kids want and need to do. Standards become indicators of success, not the outcomes.

Publishers have little idea what the students in your classroom want to and can read. But you do. And because you know, what will you do?

Take care,

Matt

P.S. Full subscribers can access the print-friendly version of this article here. Please share this resource with your colleagues to facilitate professional conversations.

Looking to take control of your reading instruction while trying to deal with the constraints of a commercial literacy curriculum? Check out my guide, Resist the Script: Five Critical Questions for Teachers to Adapt, Adopt, or Develop a Literacy Curriculum That Works for All Readers and Writers. This resource offers practical and easy-to-implement strategies for any context or situation. It’s on sale for only $7.

I coach individuals and teams around a variety of educational topics, including curriculum development, data analysis, and strategic planning. Contact me if you would like to learn more.