“I Like to Write, and So Do They”: How Our Beliefs Influence Our Students

Plus Four Ideas for Promoting a Positive Attitude Toward Writing

A stack of 1st grade how-to books caught my eye while students worked independently on their math sheets. One student, seated next to the stack, pointed to a black bin in the middle of their classroom library. “That’s where our published books are.”1

Taking the hint that the stack I had spied was not ready for a public audience, I walked over and sat next to the black bin. Students had stapled together their books and colored their covers. Snakes, My Sister and other topic titles adorned the front. One title caught my eye: Babies. Finding the author, I asked her to tell me more about her book.

She explained that she knows a lot from going to a babysitter. “I learned all about them: what they need to eat, that they should sleep, and how to make them happy.” This was not “taught” to her; she was observant of how the babysitter took care of an infant while she was in daycare. (I noted that the student was not required to also read a book on the topic. Her source of knowledge was validated by the teacher.)

Examples like this remind me that reading and writing are, to at least some degree, taught by our actions as much as any strategy we might use. How we treat books and how we engage with text convey our beliefs about literacy. Just as this 1st grader saw how the babysitter worked with an infant, our behaviors while reading and writing surfaces our relationships with the content and the discipline.2

One key belief within our school’s classrooms is the connection between reading and writing. These two are too often separated by curriculum resources and programming. Yet it is a disservice to treat one separate from another. Many writers point toward their reading life as their source of inspiration and guidance for their work.

“What is hot like fire?” Another student wrote about volcanoes. Assuming he had not made a recent trip to Hawaii, I asked if he learned about this topic from a book. “Our teacher read it aloud in class.” He went on to explain that, once he stated that he wanted to write about volcanoes, his teacher tucked the informational text in his writing folder after she shared it with everyone.

Like his classmate’s book on babies, his writing was actually informational. I learned something! “I did not know that geysers are created by the heat from magma inside the earth. What do you plan to write next?” He explained that he already started his next book.

After finishing my notes, I walked over to the teacher and handed them to her. “Your students seem excited about their writing projects.” She acknowledged that and then pointed to the original stack of books I had discovered. “Those are actually the assessments for this unit.3 They had to tell me what they learned about nonfiction. I am not even sure they knew it was a test!”

As we discussed how having multiple writing samples over the course of the unit gave her more artifacts to assess their progress, one student who was working quietly turned toward us, leaned over the back of the green couch he was sitting on, and told us, “I love to write.”

She waved her hand - there you go - in acknowledgment. “I love to write, and so do they.” She shared that writing was her favorite subject to teach when at kindergarten in her previous role. “Well,” I responded, “I am sure you are seeing them grow in 1st grade.”

A positive attitude toward literacy is infectious. Students can “read” their teacher, unconsciously observing their attitude about this discipline both verbally (i.e. tone of voice, language choices) and nonverbally (i.e. where the books are located, how involved students are in making decisions about the writing process). Thinking about my own classroom career, I was certainly not an expert teacher of readers initially. Yet my enthusiasm for literacy (“You don’t have a book for independent reading? Let’s look together.”) helped make up for my inexperience and my lack of informed beliefs.

Strategies for teaching readers and writers is of course important. Yet if we don’t have a positive relationship with language, or we do not make our beliefs about literacy evidence in our environment, students may never aspire to engage with text at a deep, personal level.

Four Ideas for Promoting a Positive Attitude Toward Writing

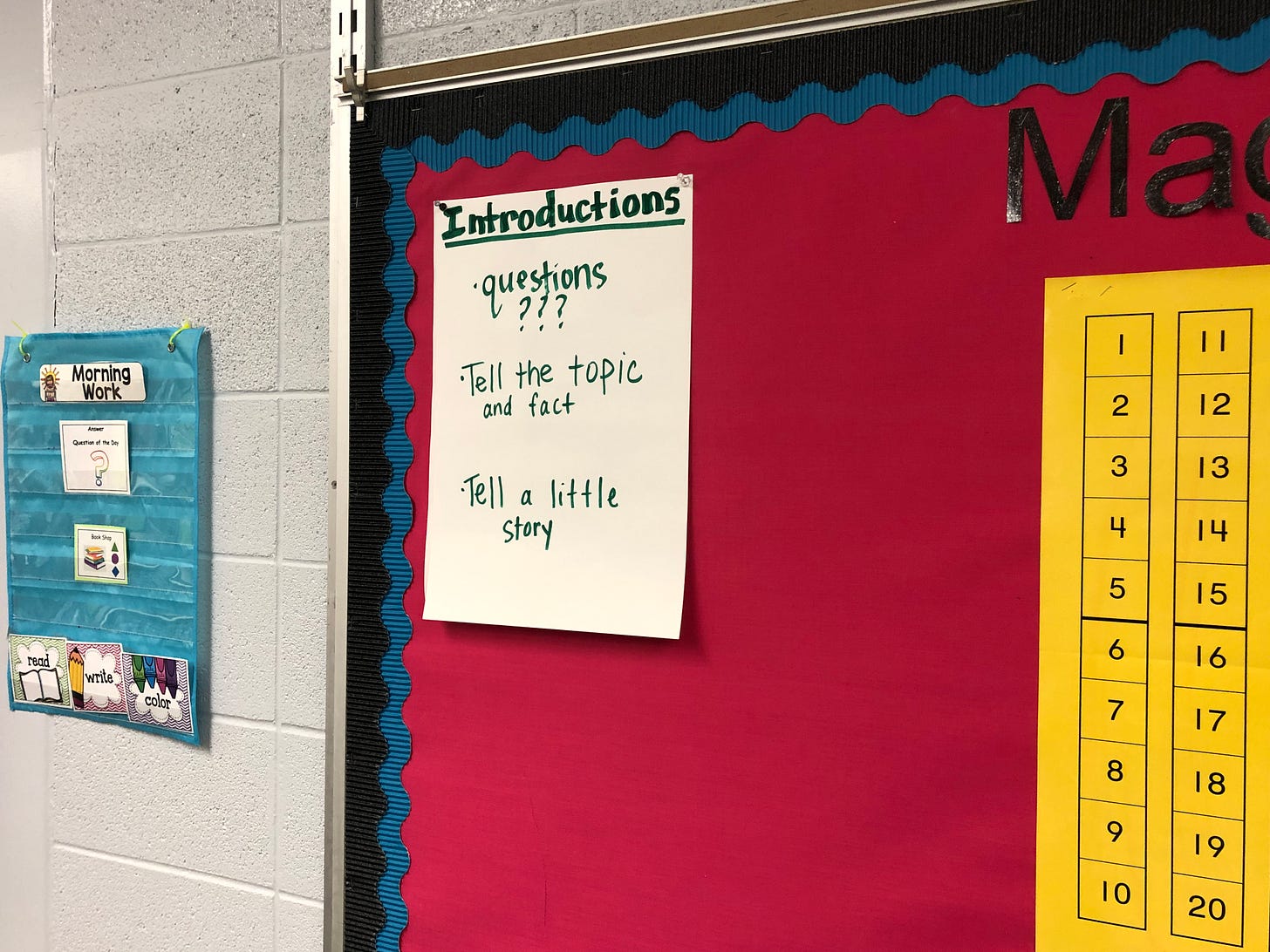

Set up your classroom environment for writing, revising, and sharing. Dedicate space for students to write quietly, to work in small groups for peer sharing, and to celebrate pieces as a whole group.

Provide lots of tools and choices for developing students’ writing practice. Computers and paper/writing utensils should both be available. Allowing for multiple options within each mode - laptop or tablet? - can also empower students as an “authority” in their writing lives. Discuss the pros and cons of each tool.

Spend more time writing than revising or publishing. As the saying goes, “Writers don’t like writing — they like having written.” Give students ample opportunity to complete many short pieces. Success begets success. Eventually they will choose to publish a piece they are proud of and want to share with the world.

Minimize rubrics and maximize examining quality writing to internalize expectations. Reading aloud excellent literature is one approach. Another activity I enjoyed doing with my students was reading two pieces of sample student writing and asking, “Which one is better?” The class would get into healthy debates while using the disciplinary terms. (If you must use a rubric, make it a one point rubric4 and simply copy/paste the grade level standard into it.) Of course, we see quality most often when students have a meaningful purpose and an authentic audience for their writing.5

Enjoyed this article? Share it with a colleague.

In this video, Matt Glover talks about the importance of kids making books.

For more information about educator’s beliefs about writing in particular, check out this article by Hall and White (The Reading Teacher). They provide a self-assessment for your own writing beliefs, a tool I have utilized during professional workshops.

NCTE’s Position Statement on Writing Assessment is worth your time to read, and to keep for future professional collaboration.

Meet the Single Point Rubric (Jennifer Gonzalez, The Cult of Pedagogy)

Interested in developing your own professional writing practice, or need support in sustaining it? This spring, we will meet for the third of three times via Zoom to share our work with colleagues and talk shop. (This is for full subscribers only; see button below. Subscribers have also been receiving monthly writing tips, for example #7: Revise Only as Needed.) Email me at renwickme at gmail dot com for more information.