Leading Literacy: Communicating Feedback Through Questioning

Teachers are usually looking for leaders to listen.

A basic assumption of feedback is that it’s most effective when delivered from an expert to someone with less expertise. Maybe that works in athletics, or in a clear separation of knowledge and skill such as a mentor/mentee relationship.

However, between principal and teacher, it is not that simple. Teachers are expected to be and should be trusted as professionals. So to come in and simply “tell it how it is” can lower expectations and may violate trust.

For example, in a previous school, a teacher asked me to preview a novel she was considering for a read aloud. “There’s a scene that I am wondering if it is too mature.” I agreed to read the novel over the next couple of days and get back to her.

The scene was mature; I suggested to the teacher she find another book. “Oh, but I really like this one.” She disagreed with my assessment. Not sure what to say, I reminded her that she had asked me what my opinion was.

Not my best response. Even though I was likely right, instead of engaging in a conversation and supporting self-directedness with this teacher, I opted for simply stating my opinion. What could I have done instead?

Communicating Feedback Through Reflective Questions

“Genuine questions are the foundation of professional conversation because they require the instructional leader to listen and to withhold judgment while learning about the teacher’s goals for the lesson and the context surrounding the observed portion of the lesson. It may be impossible to hide the assumptions behind a question - for example, if you think a particular aspect of the lesson was unsuccessful, that’s likely to be apparent to the teacher - but genuine questions allow you to remain open to the possibility that your assumptions are incorrect.”

- Justin Baeder, Now We’re Talking! 21 Days to High-Performance Instructional Leadership (Solution Tree, 2018, pg. 107)

Instead of giving advice to teachers, even when we feel we have permission, asking a reflective question can help us push pause on our assumptions. Reflective questions also create a space in which teachers can become more self-directed as professionals and ultimately own their learning.

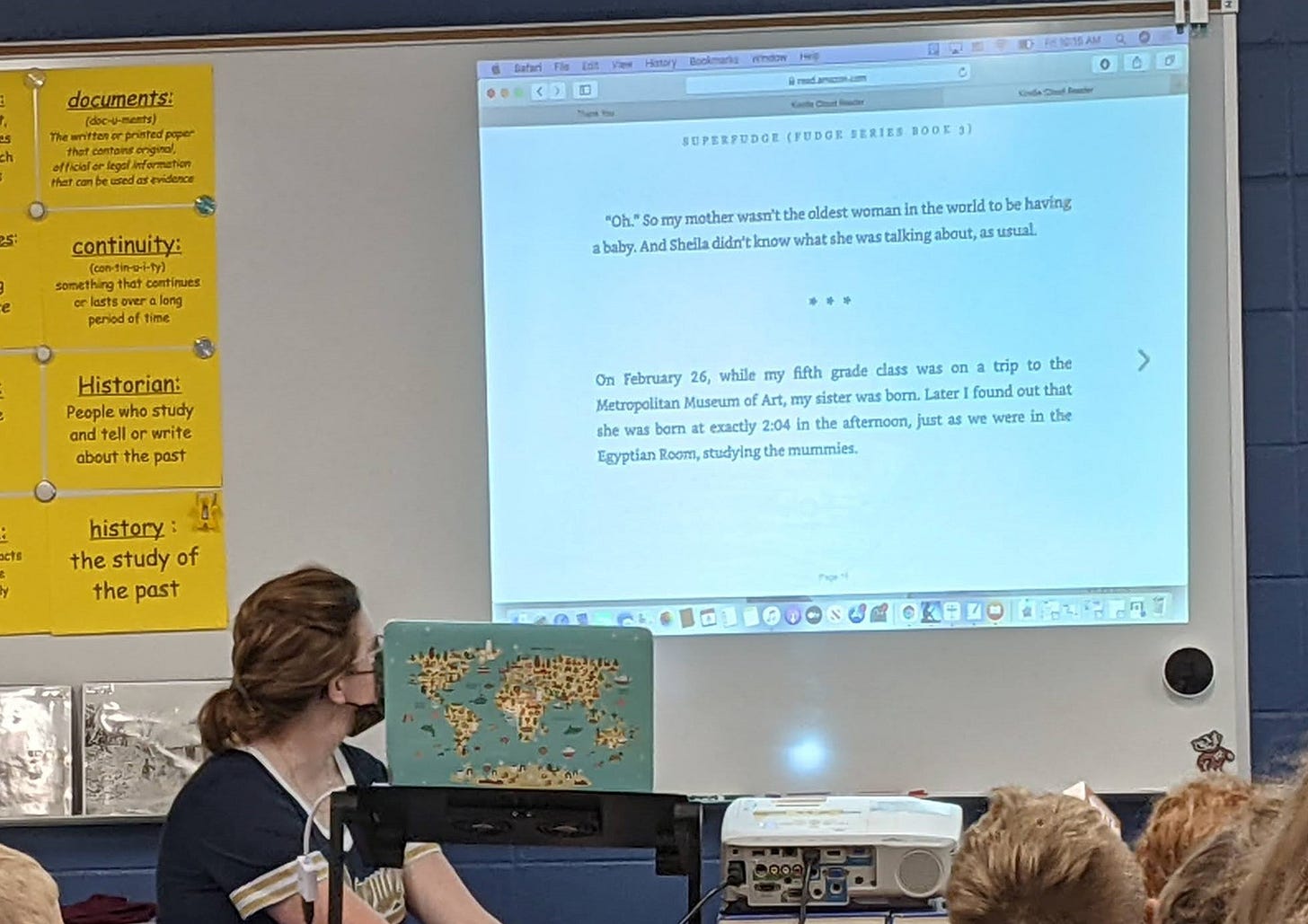

For example, I observed a teacher reading aloud a book, Superfudge by Judy Blume. She had the text projected on the board as she read aloud. After taking notes, I shared with her that "virtually all of her students had their eyes on the text as you read aloud."

But I did not leave with just this affirmation. I asked a question:

"What led up to you displaying the text on the board, perhaps from a previous read aloud?"1

My assumption: Students attended better to the read aloud when they could read along.

What I Learned: The teacher explained that, once she learned fluency was an issue for her students based on fall reading assessments, she made the decision to have the text displayed for all to read with her. The read aloud became a shared reading experience. It was an opportunity for kids to follow along with the teacher, the best reader in the room.2

If I had not asked this question and just ended with a compliment, I would have never learned the thoughtfulness and creativity in her decision-making. My question communicated feedback - to me. I understand this teacher's practice a little better. My capacity as a supervisor and coach has improved.

This is when feedback is most powerful: as a reciprocal and continuous process of sharing information for collaborative professional growth. Questioning is the entry point for this learning.

In another example, a teacher was working with a student 1:1 on foundational literacy skills. They were practicing a sound pattern while reading a simple text.

What I noticed and wrote down was:

The student would try the word out,

Pause in the middle of the word and look up at her teacher,

The teacher would patiently wait until she finished, and then

Recognize the student’s successes and guide her to reflect on her efforts.

After sharing my notes, I posed the following question to the teacher:

“Tell me about when you paused as the student looked to you during the individual reading lesson. What went into that choice?”

My assumption: The teacher paused to allow the student to try the skill out and see if she could do it independently.

What I Learned: After posing the question, the teacher agreed but also expanded on my inference. “This student needs more time to process what she is reading and thinking.” I thanked her for sharing that information as I was unaware of the processing challenge.

This is when feedback is most powerful: as a reciprocal and continuous process of sharing information for collaborative professional growth. Questioning is the entry point for this learning.

If I could go back and have a second chance with the exchange I described at the beginning of this post, I might have led with a question. For example:

“I appreciate you asking me for my perspective on this. What led you to asking in the first place?”

This answer might be obvious, but I would not be looking for just the answer. My goal would be to support the teacher’s capacity for decision-making. She might have responded with, “Well, obviously the scene is pretty mature…” I may have then clarified that, if it is truly obvious, then what was my purpose for my presence: To simply offer a second opinion, or to engage in a deeper discussion regarding how to determine appropriate content for students at this age?

Conversation by conversation, we can help develop our teachers’ capacity for self-directed leading and learning by first listening with reflective questions. Feedback is communicated - not “delivered” - when we surface teachers’ thinking and make it visible.

Justin Baeder offers ten questions as stems for promoting teacher reflection in his book. He also offers helpful notecards with these question stems to carry with you during classroom visits.

The phrase “the teacher is the best reader in the room” comes from Kelly Gallagher’s book Readicide: How Schools Are Killing Reading and What You Can Do About It (Stenhouse, 2009).

Love this reflective, wise post on giving useful feedback through asking genuine, clarifying questions.