For this article club, colleagues and I explored the following questions and more as we discussed Paul Emerich France’s article (ASCD Blog).

How can schools balance instructional transparency with teacher empowerment?

Is there a reasonable rationale for why principals can expect lesson plans to be submitted to them?

If teachers are expected to be leaders, what are the conditions in which they can thrive?

The following guests joined me for this enlightening discussion:

Debra Crouch, Teaching Decisions

Mary Howard, Literacy Lenses (Twitter)

Don Marlett, Learning Focused (Twitter)

Listeners will walk away with a more nuanced understanding of effective vs. ineffective lesson planning, the conditions for teacher agency, and how to build a school culture based on trust.

(Go to the end of this post for the full transcript of our conversation.)

Additional Benefits for Full Subscribers

Full subscribers enjoy additional resources:

The ability to comment on all posts.

The opportunity to participate in these live conversations via Zoom.

Access to the video recording archive of professional conversations, as well as a copy of the discussion guide which can be used to support similar continuous improvement efforts in your context.

Video Archive: Should teachers be required to submit lesson plans?

Watch now (37 mins) | In this recorded conversation via Zoom, Debra Crouch, Mary Howard, Don Marlett and I discuss the challenges and the thinking behind requiring teachers to submit lesson plans to their building administrators. The text that supported this article club was a blog post for ASCD titled “

Become a paid subscriber today to enjoy all of these community benefits.

Coming Up:

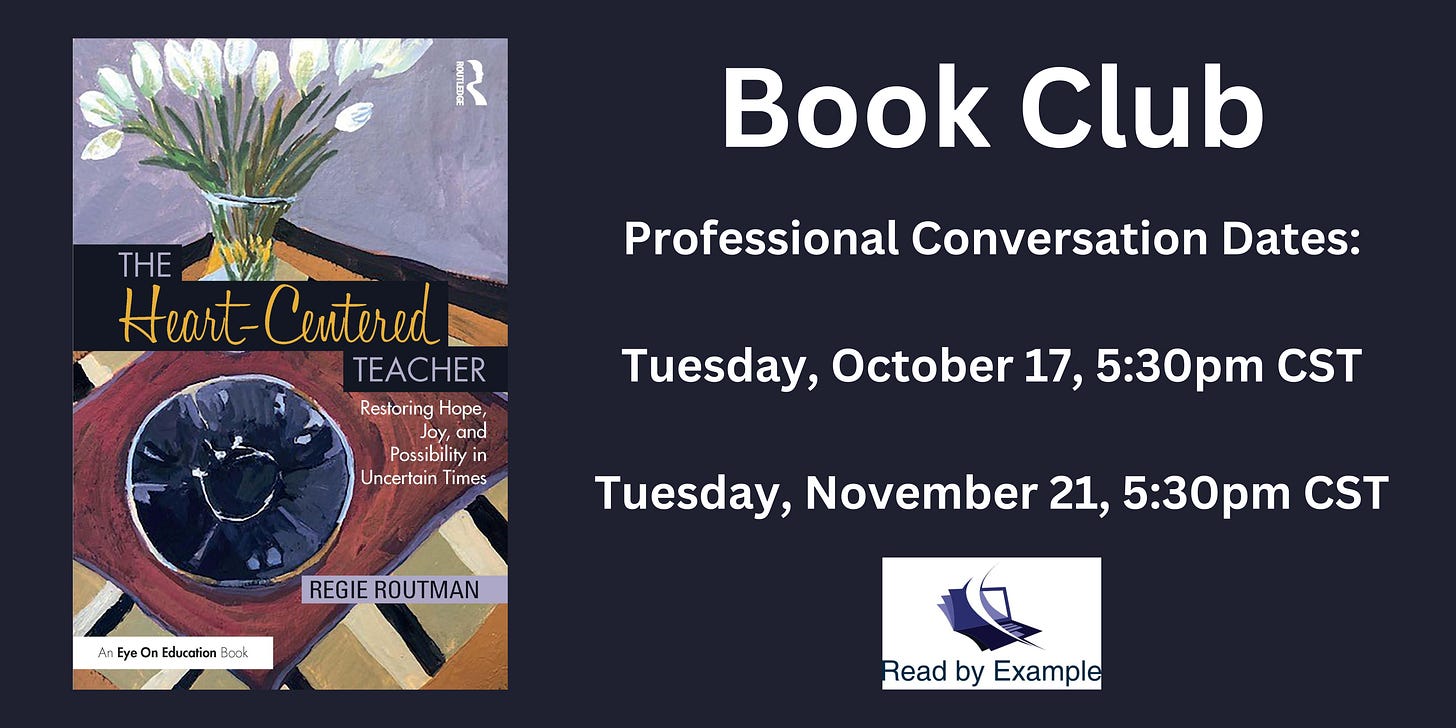

October & November Book Club, The Heart-Centered Teacher by Regie Routman

“How do we find hope and possibility in challenging times?”

In her latest book, Regie Routman offers all educators “a refreshing chance to pause, take a breath, and reflect on how you and your students can live more compassionate, generous, and authentic lives.” The Heart-Centered Teacher is about more than literacy; it’s about “developing, nurturing, and sustaining caring relationships - in our teaching lives, our home lives, and in the happy intersection of both.”

You are invited to join us this fall in an eight-week book club around this text. You can purchase Regie’s book at one of the links below.

Full subscribers can participate in two monthly conversations via Zoom around the book on the following dates:

RSVP here.

All subscribers will be able to post comments on discussion threads related to the book on the following dates:

October 10th: Chapters 1-2

October 24th: Chapters 3-5

November 7th: Chapters 5-7

November 21st: Chapters 8-10

We will be using the study guide and additional chapter resources to help support the discussion, found at the book’s companion site.

All of this is made possible through the generous support of full subscribers - thank you!

Full Transcript

(generated by Rev.com; the AI is to blame for all grammatical errors. :-)

Matt Renwick (00:02):

Welcome to Read by Example, where teachers are leaders and leaders know literacy. And I'm welcoming here again, Mary Howard, Debra Crouch, and Don Marlett. Mary, if you want to start, just share a little bit real quickly about yourself, what you do.

Mary Howard (00:18):

Sure. I'm a literacy consultant, still heavily engaged in education, living in Honolulu, Hawaii, and have been a teacher for 51 going on 52 years now.

Matt Renwick (00:33):

Deborah,

Debra Crouch (00:35):

I'm Debra Crouch. I, I'm also working as a literacy consultant these days and just was with second and fourth grade teachers today talking about the practices in their classrooms, and this was very applicable to some of the work that we were doing. So I'm excited about this conversation.

Matt Renwick (00:55):

Awesome. Yeah.

Don Marlett (00:58):

Hi, I am Don Marlett with Learning Focused. So I thought this would be a fun one to join. Alright. Specifically within an instructional framework is one of our focus areas,

Matt Renwick (01:15):

And I'm familiar with all of your work, either through reading or presenting. So this is a very knowledgeable group. I'm honored to be here. So today's topic, and again, the intention here is to just engage around a topic of interest that people are talking about. And this was something that was getting debated on Twitter, whether or not teachers should have to submit lesson plans and looking at the bigger topics of school-wide expectations, balancing that with teacher empowerment and the articles by Paul Emrich, France for ASCD blog. So the question I had just in mind was, should teachers be required to submit lesson plans or do we need to ask a better question? I get a sense there's more to the issue here at a deeper level than just lesson plans, but we can get into that. And the other purpose we record these conversations is just to demonstrate how to facilitate a professional conversation.

(02:14):

And this is the heart of professional learning. We don't talk about some of these big topics in schools because they could be too contentious. You're afraid it might spiral into an argument debate. And so hopefully through this process, through professionals such as ourselves that we can demonstrate that for our colleagues. So everyone gets this guide who is a full subscriber to the newsletter. So thank you to everyone who is a full subscriber, really important to have norms with some of these conversations. Working norms, agreements, I just use some from the Peloton group. A dialect should be a basic attitude. Create safe spaces, include all relevant parties in a dialogue. You listen, let everyone share their experiences, ask questions, talk about difficult topics and contribute to forgiveness and reconciliation. And one thing I've seen presenters do is to ask the audience each person to like, which one are you going to focus on to add during this time together? Which one do you want to really work on? So that's a strategy you might want to try. So just to kind kick things off, but what are you listening to right now? Just more of an inclusion activity. It doesn't have to be music, it could be a podcast, it could be anything nature.

(03:36):

I'll go first.

Don Marlett (03:38):

Go ahead Matt.

Matt Renwick (03:41):

I'll be the first to go here. I've been listening to a huberman Lab podcast. Andrew Huberman is a neurobiologist in California and he's a podcast and just talking to a psychiatrist in the East Coast, Paul Conti at Harvard Medical School about mental health and talks about the framework for mental health. So I found it very illuminating and I want to share it out at some point for all schools. I think the framework's very helpful in terms of how we can help kids and even adults. So that's what I'm listening to.

Don Marlett (04:18):

I just started listening to writing for Busy readers. I saw it, I follow Angela Duckworth and she posted it. And so it was a good book, but also because whenever we send emails from our company and all that stuff that everybody is busy. So how can we make it so that they can actually read them? Since we all know it's hard to read our own emails. It's very good so far.

Matt Renwick (04:47):

And it was a book or it was a podcast?

Don Marlett (04:50):

It's a book. So I'm just using reading the audible version, listening to the audible version of it. Cool.

Mary Howard (05:01):

Okay. Well, I'll go. I just finished listening to, I'm a big fan of Dr. Andy Johnson's the reading instruction show. What I love about Andy is how clear and strong he is in talking about some of the issues. And so I enjoy listening to that and I enjoy taking notes and just kind of thinking it through. He usually has a podcast maybe once every couple of weeks or so, and it's really very well done.

Matt Renwick (05:37):

Nice.

Debra Crouch (05:38):

Well, I'm going to fess up and be the one who says I am not good with podcasts because the podcasts that are professional, I want to be sitting and taking notes on. People will say, oh, listen to it while you walk. Doesn't work for me. I want to take notes. And I can't do that while I'm walking. So I haven't figured out really how to put podcasts. My life very well. I can listen to the Fluffy. I absolutely loved my brain. Just went absolutely did. On her name, Julia Louis Drive's podcast series. I don't know if you saw that, where she's talking to women older than her and she's like, what can I learn from you? So I listened to that podcast, but I was thinking about what am I listening to? And I was just listening in the car to this brilliant artist called Rianna Giddens. Do you know Rianna in her work?

(06:32):

How do you spell her name? Rianna? I don't know if I'm pronouncing it correctly. Nan like the Fleetwood Max song, Giddens, G I D D E N S. And saw Americana music. And I learned about her through a book that I was reading on creativity and they profiled her in this book. She's won a number of awards, but she decided that she didn't want to be on that I'm into the popular music and going on the tours and doing that sort of continuing to grow and be popular in that way. She decided to focus inward in her writing and in her songs and in her musical choices. She's one of the most glorious voices, I think. And that's the word I would use. It's a glorious voice. So that's who I've been listening to. But when you say that, I'm like, okay, I listen to music, not a podcast listener, really. So anyway, so that's what I've been listening to right now.

Matt Renwick (07:38):

Nice. I like Fluffy.

Don Marlett (07:42):

And Debra, I feel your pain. I never last very long. When I'm listening to audible books, my mind starts racing, so that's why it takes me. I go back and forth between that and Fluffy, so I'm like you, I can't just sit there and listen for the whole thing, which doesnt work when you're driving. So I can't listen to her for very long.

Mary Howard (08:04):

And sometimes when I'm walking and I'm starting to listen to a podcast, it's bad because I pull out a pen and I end up taking notes all the way down my arm and now sit at the, I try to just put a marker and then like you said, I need to write it down so I listen to the podcast at home and type out the important things. I like it, but yeah, it was bad on my skin.

Matt Renwick (08:30):

I heard that's the best way to do it, is to listen and then go home and then write down what you remember paraphrase. And that actually is the best way to synthesize, which I don't do. Of course I do it. I'll bring up Google keep notes and I will record myself and it will transcribe what I say. But yeah, I think that's the best way is just to listen and then write it later. Alright, so the article, thanks for sharing, I'll put those in the notes. The article again is why teachers shouldn't have to submit lesson plans. And this piqued my interest was posted on Twitter, and another pretty well-known educator, former principal had said, I just disagree with this whole thing. And I like that when there's disagreement, I think that's good. The principals, we can require to have lesson plans submitted to us, and I think that's important, and I think he would probably have some very good reasons.

(09:32):

But the reasons that Paul Emerich France listed were to not submit them is he started his first two weeks teaching and he's like, I wrote them all at length and after two weeks I was exhausted and I was constantly changing them because I was paying attention to my kids. I wasn't able to be responsive because my lesson plans were all planned out literally. So he just noted that first administrators don't have time, so they're not going to read hundreds of lessons every week, creates more paperwork. The second reason is traditional lesson planning is unsustainable. He likes five questions, which I thought were good, which is what should students know and be able to do by the end of the lesson? How will I know if they've learned? So it sounds like PLCs, how will I provoke curiosity and discussion? How will I orchestrate instruction? How will learners reflect on that lesson? So that's his framework he uses for lessons, a much abbreviated version. And the third reason is teachers feel micromanaged. So just thinking about those three reasons that France lists, what are just your initial thoughts on that?

Mary Howard (10:44):

Well, I'll just start by something that he said early on, and I thought it really kind of was a crux of the whole article. He said, plans change, they have to, teaching is unpredictable and uncertain, especially when 20 or more human beings are along or this ride we call learning, steering the ship with their questions, emotions and thoughts. Teaching cannot follow a script. And that's one of the problems that we're seeing right now with scripts and very controlled plans because it's in the moment teaching in my mind, there's nothing more important than that in the moment teaching. So having a plan is really important. I thought it would be very difficult to write plans with all five of those questions, but I was certainly really intrigued by them. But I think that really is the crux of the article for me, that if we don't leave room for that in the moment decision-making, that there's no way we could plan for it, then how are we really being responsive to children as opposed to being responsive to whatever it is that we're turning in.

Debra Crouch (12:05):

It was interesting because when I read this for the first time, I had a lot of different ways of thinking about this because I do a lot of this with teachers in my work where I'm planning with teachers and this work. And so one of the things that I wrote as a note was what does a lesson plan look like for this author? One of the questions that I had, because I've been in situations with teachers where I've gone in thinking, okay, we're going to do some planning, and I'm thinking bigger planning, like unit kind of planning or a series of lessons kind of planning, but the teachers think we're planning a lesson and that we're walking away with it. So we had to do a lot of clarifying of what we mean when we talk about planning. There's that the unit plan, the weekly plan, the daily plan.

(12:59):

And then one of the other layers that started popping in was the prep. What does it mean to prep a lesson, right? You have your lesson plan, but you still have preparation. You have to do kind of in that moment kind of thing. So I think that was a question that I had within this was like, okay, what exactly are you talking about when you talk about lesson plans and turning them in? Because I know when I was a teacher, we did turn in weekly lesson plans, and one of the things that I thought so much about was that as a new teacher, I didn't like doing it. So I could totally relate to his thing about teachers feeling controlled and micromanaged. But in hindsight now I can see that it forced me and pushed me to be prepared in a way that I probably would not have been had I not had to make sure at eight o'clock on Monday morning.

(13:51):

Those were in my box and I knew it was just more of they just wanted to make sure we were planned and they could come in at any moment. I may understood how they were working with it, but once I learned how to, in a way they didn't care how we turned it in, it didn't matter what it looked like, it was just that you had it in there. Everybody looked at different, everybody's looked different. But I felt like once I learned how to put it onto paper, then I felt like I actually knew what I was doing. It was more like a to-do list for myself, just with the notes and excel. Anyways, it was just an interesting, I'm talking too much, but it was an interesting way of looking because my first question was like, okay, what's he talking about when he talks about a lesson plan? What exactly would that look like?

Matt Renwick (14:36):

And Debra, you make a point here that France recommends in the end of the article that for new teachers, but I think any teachers would benefit from having their coach learn the art of planning and prepping and what's the difference in what you're talking about? I would just be really good practice for any teacher PLCs, but working with coaches like you, Deborah or Mary or Don, I think that would be just powerful professional learning for anyone. Don, what are your initial thoughts here?

Don Marlett (15:06):

Yeah, it's funny because that I follow a couple of Facebook principal groups and this always seems to be divided down the line. When a new administrator asked that question, I think I went back to what Mary and Debra were saying is depends on how you define the word plan. If you define it as a script, a hundred percent agree, scripts are not in my mind a plan. So one of the things that we do sometimes is just what do you define a plan? How do you define that? We do that in one of our trainings and the whole point of it is when we get to the end of that with teachers is that nobody ever says it's rigid or it's a script. It's always flexible, but having an outline, like writing an outline for an article or a book or anything like that without having an outline, it makes it harder to be more flexible in our view.

(16:00):

So that was one of my thoughts with that. And also the other half of that was the admin piece of it. And again, it depends on if you define admins, reviewing every single component of every single lesson plan versus pieces. This week I'm just going to look for how I'm going to launch my curiosity and discussion, and then next week or two weeks down the road, what does that look like? And the way that he defined it of every single teacher or every single week is not sustainable. Absolutely. It's not sustainable for admins to be able to do that. And if that's how you define it, then I could see why you would vote against it.

Matt Renwick (16:42):

And just coming out of 16 years as a building principal, I can vouch for there's zero time to viewing everyone's lessons. The only time where I would really find I would find the most valuable when I'm doing unannounced mini observations that were required to do, I would go when I would read the lesson and then observe just to see are their intentions, their actions aligned with their goals and what are the standards? And I always found that helpful to have the context, but oftentimes as many times it's not. I could figure that out just by observing the lesson. I didn't need to look at the lesson plan, especially if it was a very good lesson, it was very explicit. I would never even need to look. So good instruction.

(17:30):

The lesson plan is very visible, right? In the classroom, I guess I think of lessons kind of as a map. It's a set of directions. You don't necessarily have to go the route you necessarily plan for. You might go on a diversion. So I think France's ideas here of provoking curiosity, orchestrating instruction, like the term verb, orchestrate versus mandate or direct, I think you're orchestrating kids is learning, but you're trying to empower them at the same time. So the compass is the kids, right? And the learning that you're trying to accomplish and the lessons are more of the map. So Deborah kind of hinted at this, but the second question I was wondering, and feel free to pose your own questions, but just playing devil's advocate, what were some other reasons why you would require these and lessons?

Debra Crouch (18:26):

So I work in a school where the teacher teams plan certain parts of their days for each other, their dual language school. So someone's the planning, the s l A part, someone's planning the e l a part, someone's planning the science, the social studies, and they do a lot of sharing of that. And so one of the conversations that we're talking about is what would a teacher, how detailed do your plans need to be when you share them out with your team members, team members so that they're able to understand the focus of the work and what you're hoping to accomplish. So one of the things I'm planning to do is to share these five questions with them because I think that would be really a strong part of the conversation when you think about someone else taking your plan, which is always a little awkward for me, just that whole concept of trying to take someone's plan. So when he was talking about can you pull off a lesson plan? I was like, that whole in the moment, pull a lesson plan when you're in a pinch, you need a last minute lesson. And I was like, okay, what's that about?

(19:42):

But if you are sharing those things, that might be a reason why you're putting more information together on a plan. So that's not necessarily for an administrator, although administrators would maybe look at that, but if you're sharing with your colleagues on your grade teams and things, I was thinking about that in terms of when you might need to do more lesson planning in

Matt Renwick (20:05):

That way. We facilitate collaboration and communication, I think too, a grade level teachers, but also classroom and special education teachers, classroom and interventionists technically powerful. Yeah, that's a good point.

Mary Howard (20:21):

Yeah. And, you said at one point when you were talking earlier that teachers were encouraged to come up with lesson plans that work for them. And I think that's what gave me a little bit of pause when I looked at the five questions, which are perfect, but it's so easy to turn something into rigid by saying it has to look like this. The one that I've always used is just three columns, and the first one was what I know, meaning what do I know about these children? What do I know about this child? What do I know about this small group? So just what do I know? And that's the piece I think we often don't do. The second is what I think what I see is the lesson, but the third one for me was the most important at all. What did I change in the moment?

(21:11):

And I use different colors and I say to teachers, we have to understand that a really good lesson plan is going to change based on you can't anticipate what children say or do. And I think sometimes we dishonor that. So I always would have teachers put in a different color, these are the things that changed and that became the professional conversation. Why did I take more time here? Or why did I have children generate their own? What are you thinking about or what are you wondering? And it's really important to me not just to have, here's the plan, even though those are five great things. Here's the plan and here's five things. I want them to create their own structure. But I also want to, even if you don't have a column, say now go back at your lesson plan after the fact and just jot down in color, these are some things that I changed or I added a question, or children generated this question and we spent a little time there.

Matt Renwick (22:21):

Mary, is that resource you mentioned, is that available anywhere? Is it in one of your books or,

Mary Howard (22:28):

I feel like I talked about it in good to great teaching because good to Great teaching was a lot of different forms that teachers would teach and look at. And that probably would be the book where we talked about it the most. And one of the things I actually did in that book is that I would come in and observe a lesson of their whatever they wanted. We'd have a conversation about it. We talked about what might they have done differently, and then either with that group or another group, they redid that lesson with the changes based on our conversation. So it probably would come from good to great teaching.

Matt Renwick (23:08):

I think that'd be, if you find time, I think that'd be a powerful article somewhere with a template LinkedIn, like Paul has in his article, he has that link in the article. But I think that would be really helpful resource.

Debra Crouch (23:22):

I always try and think about that. The purpose of the plan is to help you envision, to me, I always say to teachers, the reason that I even craft this detailed plan is that I'm envisioning what happens or possibly could happen. Because when you think about sitting in front of kids and being responsive to kids and knowing your learners and how you put that into practice is I've got to think about, okay, we might go here, we might go here. I know this kid, I know we're probably going to go here and you're envisioning. And for me, it's thinking about, okay, what might I say in the moment? Because I think sometimes we think responsive means off the cuff, and to me, being responsive means I've anticipated some of the kinds of things that could happen based on the kids and based on the text and what I know.

(24:14):

So his question about facilitation I think is really an important piece, but it's like if you get to the place where you think that planning just means I'm envisioning it happening, and then I can reflect back on it afterwards and say, okay, well this part, ooh, didn't see that one coming. You always have those moments where you think this was going to happen or this is going to be the word that the kids are going to get stuck on. And then there's like, they didn't have that problem, but it was this problem and you didn't see that. I said, children always teach you about teaching. They'll always teach you about what the issues are in the book if you just are a good listener, what they talk about.

Matt Renwick (24:51):

I like that. Don, any thoughts here?

Don Marlett (24:53):

Yeah, I think in our experience, we work with a lot of schools that want to increase the use of specific high yield strategies, maybe collaborative pairs, something like that. And so a lot of times the teachers will be given the professional development. And what we all know now is that professional development doesn't really change necessarily behavior of teachers in a large quantity. So you have to of course monitor that in a couple of different ways. And so in our experience, the more that they've planned them and put them into their lesson plans, the more likely they are to incorporate them into their classrooms. So that would be something if I want a higher percentage of collaborative pairs and specific type of collaborative pairs within my school, and that's what my goal is for increasing student engagement, that would be something that I would monitor inside of a lesson plan that at least they're planning them out to see if when they're going to use them. And our experience is that similar to what you just said, Deborah, which is the higher level of collaboration, requires quite a bit of planning, a simple collaboration of just simply talk to somebody in your group doesn't really require any planning. And so that's why we see, at least in my experience, a large percentage of that version of collaboration, which is not necessarily the biggest impact. It just happens better than of course, no collaboration. But there's different levels that just seem to have require more planning with inside of that.

Matt Renwick (26:28):

Don. That's where my brain was going too, is to use that information in the lesson plans as an administrator or an instructional coach to see how our teacher's doing with, like you said, high yield strategies, or are they just go to page 1 29 and answer these questions, which isn't a lesson plan, it's just a to-do list, or are they more so to where Francis' questions are around is what do they want them to know, be able to learn? I appreciate Mary and Deborah's point of looking at the kids first and then thinking about the content. So think these all make sense. The third question I had is could we be asking a better question, not why teachers should or shouldn't have to submit lesson plans? What is this really about? And I'll just note that I circled the third reason why we shouldn't require lesson plans submitted is micromanaged and to the point of where teachers are feeling disempowered.

(27:30):

And what that leads to is a lack of agency in teachers feeling like they're not trusted, feeling like they can't be trusted to deliver the curriculum. And there might be situations where there's a teacher to where they aren't doing what they should be doing, they're not even writing lessons for not requiring, they're just flipping to the next page. And there's no reflection. There's no using a formative assessments to guide the day-to-day instruction. So I understand why it's much easier just to say everyone, you're doing lesson plans and then you can use that, like Don was saying, and you all were saying is really just looking at teachers thinking their decision making and from a day-to-day perspective. But yeah, what is this really about? Is power or what are your thoughts on that?

Debra Crouch (28:23):

Well, I always think if your teachers are asking or saying things like, am I doing this right? That's when you see you've created that. They're thinking about how do I please or how do I perform in a certain way in that micromanaged kind of way. So I always think those are signals for us as leaders, if we're relying too heavily on maybe templates or here's a lesson plan format we want you to follow things like that. But I hear what you're saying. It's at some point we do need to know as leaders, okay, where are you going with that? What were your intentions? So it's like how do you balance that out? So I don't know. I was thinking, I was jotting down, I think you actually said this a minute ago, how do we support our teachers to be planned and prepared? So it's kind of that question, how can we do that? And does it have to be the same for everybody?

Matt Renwick (29:23):

Yeah, you don't want it to be compliance. And I've fallen into that trap myself as a leader. I've required things just because it's easier for me, but not necessarily responsive for them. So guilty as charged for sure.

Mary Howard (29:37):

And I wonder if we make teachers a part of that discussion more at the end. He said, when kids have teachers who feel heard and valued, those teachers will be more likely to exercise their agency to reach as many kids as possible in creative and innovative ways, whether that's a coach like you all of you are doing, or whether that's coming together and talking about what that might look like, not what that will look like, but what that might look like and bringing yourself to the table. And I think that when teachers feel agency, they pass that agency along to their children and they recognize that none of us want to feel micromanaged. And hopefully that's going to be a trickle down effect to children.

Don Marlett (30:29):

And for me, I think the micromanaged gets into feedback, get our given to principal, I mean by principals on lesson plans with that. If I might give feedback on a specific activity that they've chosen and say, oh, I think here this is a better activity, I think that's where they get lost in the micromanaging pieces versus giving feedback on high strategy or even the standard levels because everyone in that same state has the same expectations. And if I'm not using those to develop my plan, then that might be an area where you have to address inside of feedback. And to me, that's good micromanaging because a fantastic level, that's a fantastic lesson that's not on grade level is great lesson, but it also is not going to get the kids where they need to be. So that's part of it. Again, the micromanage, I think goes into the communication and how lesson planning, turning in lesson plans is communicated to the purpose of what they're doing. If it's never communicated, then I'm just going to fill in my own story and just call it micromanage. Yeah,

Mary Howard (31:39):

That's fair. Good point. Yeah,

Matt Renwick (31:43):

It could be as simple as just a thoughtful question in your lesson, this was your objective. How do you feel like the students met that objective and why do you think that happened? And just be very open-ended and not judgmental or trying to control the situation, but really trying to be more reflective, which can then be an entry point to what you're saying, Don, we're all saying here is having a conversation around is this at a high expectation level or not? And well, this has been a great conversation and I appreciate everyone being here. Any key takeaways? Again, I think in professional conversations it's good too. If I had a, we were in person, I'd have some kind of anchor chart in the back, everyone's key takeaways, but I think we got it recorded here. So anything you wanted to pull, what value was added to your practice after today's conversation?

Mary Howard (32:44):

Well, I think you said it in the beginning, the importance of conversations. And we never seem to have time to do that in schools. I mean, to be able to sit with the three of you to, hard to say the four of you, but I'm one of them to be able to sit with the three of you and just no agenda, but just have a conversation about what we're thinking, a really good, respectful, important conversation. That's what we don't leave room for in school. And that's why coaches and all of the things that you're doing are so incredibly

Matt Renwick (33:19):

Important. Thanks, Mary.

Debra Crouch (33:21):

I think for me, just thinking about how important those conversations are to help us clarify that what we mean by a lot of these terms that we use in education, like what we said, a lesson plan, because I think everybody sitting at the table will have a different vision of what that is. And as I was going into Coach with a Grade team, and it took me a couple times to really come back to that at the beginning of the year with them last year, and that I needed to make sure that we were all talking about the same thing of what we were going to walk away with. Because just as these questions can be used for lesson planning, they can also be used when you think about your professional development, what do I hope if I'm leading in professional development, what do I hope the teachers will leave knowing and being able to do? And how will I know if they're feeling confident and comfortable with that? And those same questions apply when we put that up to the adults that we support as well. So I think that's just a great way of thinking about that. This is not just about the kids, but it's also about our adults as well in the building.

Don Marlett (34:39):

I think my big takeaway is around the definition piece, even in when we're working with teachers of what those expectations are, but primarily because I do most of my individual work with principals and school leaders of making sure that they have clearly communicated what they define as a lesson plan and some of these questions that he's bringing up, and making sure that the leaders have an answer for those one way or the other of why they're not doing it or why they are doing it.

Matt Renwick (35:16):

I'll just say my takeaway is hopefully this is a model, especially for new leaders, whether principals, instructional coaches that are in charge of pd. You don't have to plan a lot. Mary said there wasn't much of an agenda, which is I think, a good thing. You can just come in with a provocative article or around a topic that's relevant to your school and provide a couple questions and just give teachers a safe space to talk and that's what they crave. And then just pulling a few outcomes out of it like we are now and thinking about maybe a few actions if we were a faculty in school, like, okay, we're going to have some intentions around some PD related to lesson planning, and we're not going to dictate one thing. We're going to include you. But that's all there is to this. I don't have to be a lesson plan expert as a new school leader to facilitate professional learning. That's powerful. So hopefully this is a model that can work you for anyone. Well, thanks again everyone for being here, and I enjoyed it. As always,

Mary Howard (36:19):

Thanks for hosting us, Matt. Yeah, thanks

Matt Renwick (36:21):

For hosting Matt. Yeah, my pleasure. Have a great night.

Mary Howard (36:25):

Okay, you too. Thank you. Good to meet you, Don. Nice to meet you too. Bye-bye. Bye.