We get what we pay attention to. Our narration determines what we experience and what we remember.

-Seth Godin

When it comes to communicating classroom expectations, leadership cannot be clear enough. Teachers want to do well; administration wants the same.

So why can it be so challenging to create clarity about what’s essential for literacy instruction? In this article, I describe the challenges in this work and offer two ways that leaders, both teachers and principals, can develop a common framework and related language necessary for ensuring all students become effective readers, writers, thinkers, and communicators.

Revisiting “Best Practice”

As a classroom teacher for seven years, there was no one group of kids like another. Each year brought unique strengths and challenges. Class sizes didn’t seem to matter as much as the make-up of personalities and student capacities. For example, one of my smaller classes (21 kids) required a lot of structure and direction. Subsequently, much time was spent frontloading before instruction and reviewing afterward. They needed more preparation and process to be successful. Other classes demanded less of my guidance because they were ready for group work and independence sooner.

So when administration tries to communicate what best practice is, it’s understandable when teachers respond with frustration. There is no one right way to teach readers and writers because students respond differently to different approaches.

In Rethinking Rubrics in Writing Assessment, former English teacher Maja Wilson offers a scathing rebuttal of the dogmatic thinking behind mandating a singular approach to effective literacy instruction (2006, p. xxi).

Just as reflective teachers must question their own performance, we must be willing to questions the methods accepted as best by the field of writing methods, an idea that may strike us as sacrilege. The very words best practice are loaded; if we aren’t following best practice, aren’t we by extension following worst practice? In addition, the term drips with authority.

I recall feeling this lack of authority Wilson describes. As a principal in another district, every school was informed that we would be adopting Lucy Calkin’s Units of Study. I pushed back, citing that our school had not had the opportunity to examine this resource through the lens of our shared literacy beliefs. “But workshop is best practice,” I was told. Our school eventually fell in line.

Professors Rachel Gabriel and Libby Woulfin echo Wilson’s concerns in the context of educator evaluation systems, while also arguing that we do need to remain open to new approaches (2017, p. 43).

Literacy instruction presents a special case for teacher evaluation because there is such range and division among practitioners and researchers about what constitutes best practice. Teachers and leaders hold deep-seated beliefs about what counts as appropriate and effective literacy instruction. Ideas about teaching and learning contained in evaluation systems may align or clash with an educator’s perspective about literacy. In the face of passionate arguments for contrasting approaches to literacy instruction, it is easy to become brittley narrow in focus, or overly liberal – accepting any- and everything.

Reflecting on this perspective, should I have been more open to Units of Study? Was I rash in resisting the initiative? Hard to answer, but I can say that the approach – of picking one right way to teach readers and writers – initially felt unprofessional. As a principal in my current building, I’ve held onto this experience as we co-create a wiser approach for guiding our current literacy work.

Embracing Frameworks for Improving Literacy Practices

During a recent survey I administered about my own capacity as an instructional leader, one teacher made the following comment: “You don’t need to be in our classrooms so much. Trust your teachers to make the best decisions as professionals.”

Fortunately, this comment was from the vocal minority; most teachers were happy with my frequency of visits. Being a professional involves knowing one’s practice, yes, but also being open to new ways of teaching. My informal approach to supporting teachers through instructional walks has accelerated our learning, especially mine.

The middle ground between having no direction for teachers and mandating one approach for all classrooms is to embrace frameworks for instruction. Frameworks provide defining characteristics of what we might call “principled practices” instead (Smith, 2017). They honor the professionalism of teachers to make decisions on behalf of the students they know well while describing the tenets of what we find to be effective literacy instruction.

Frameworks are flexible. They can be revised to reflect more current thinking, as well as expand to incorporate creative possibilities by teachers. This flexibility lends itself to better implementation of the practices that work. Through dialogue and discussion among faculty about the framework, staff deepen their understanding of the language of literacy instruction.

Next are two ways leaders can initiate and sustain this process.

Strategy #1: Examining the Framework Together

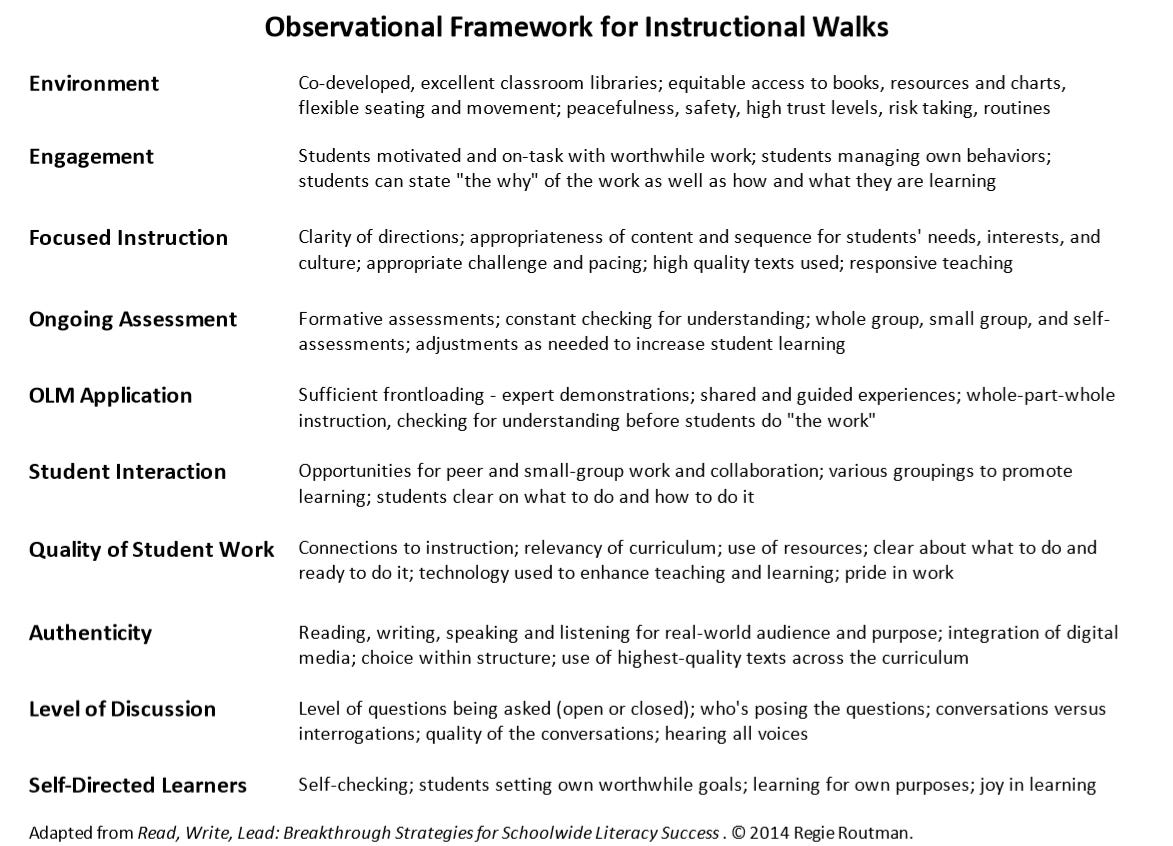

One of the mistakes I made coming to my new school was not communicating effectively what I was looking for during instructional walks. I had handed out the descriptions of the ten areas of effective literacy instruction (Routman, 2014), briefly discussed them at staff meetings, but never actually gave teachers time to read, reflect upon and discuss what everything means.

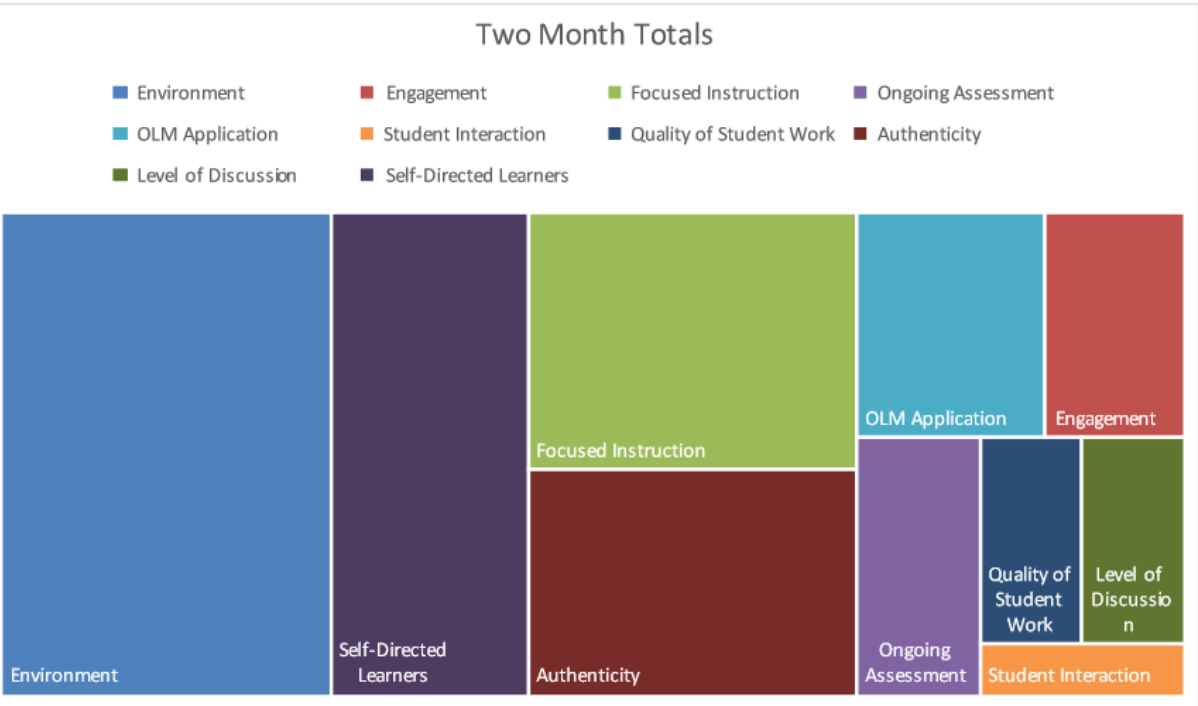

To begin again, I engaged our instructional leadership team to examine the tenets of the framework. Each member received a copy of the document. To provide a purpose for our close reading, I shared a visual that depicted the frequency in which each of the ten areas were occurring in classrooms over the last two months via instructional walks.

“What do you notice?” I asked. Teachers offered several observations and questions.

“We have set up classroom environments for students to be successful.”

“Do you notice environment because of all our work with classroom libraries?”

“How do you define ‘Quality of Student Work’? What does it look like in the classroom?”

For the last question, I struggled to come up with a clear response. I scrolled through my Evernote files, looking for pictures and walks I had captured that depicted this element of literacy instruction as aligned with the description. “Maybe I need more clarity for myself!” I admitted.

One month later, I brought in an updated graphic of the frequency of what elements I noticed during instructional walks.

I started this time. “As you can see, ’Quality of Student Work’ was an area I noticed more after last month’s discussion.” I compared it to wanting a certain type of car and then seeing that car everywhere I went. “My attention was more attuned to this tenet of literacy instruction.” Other areas, such as level of discussion, were still occurring infrequently. We agreed that this could be a focus for future professional development.

Strategy #2: Communicating the Framework Visually

“So, how do we develop an understanding of the framework with all teachers?” I asked the leadership team. While the graph was helpful for us, I was afraid that I shared it with all the faculty would hyper-focus on one area at the expense of others.

One suggestion was to be specific with teachers regarding what I was looking for. I listened and paused. “I want to be careful,” I finally cautioned. “This isn’t about what I want to see but what we should want to grow toward collectively.” My thinking: if this was my initiative, then the likelihood that it would become part of the culture was reduced.

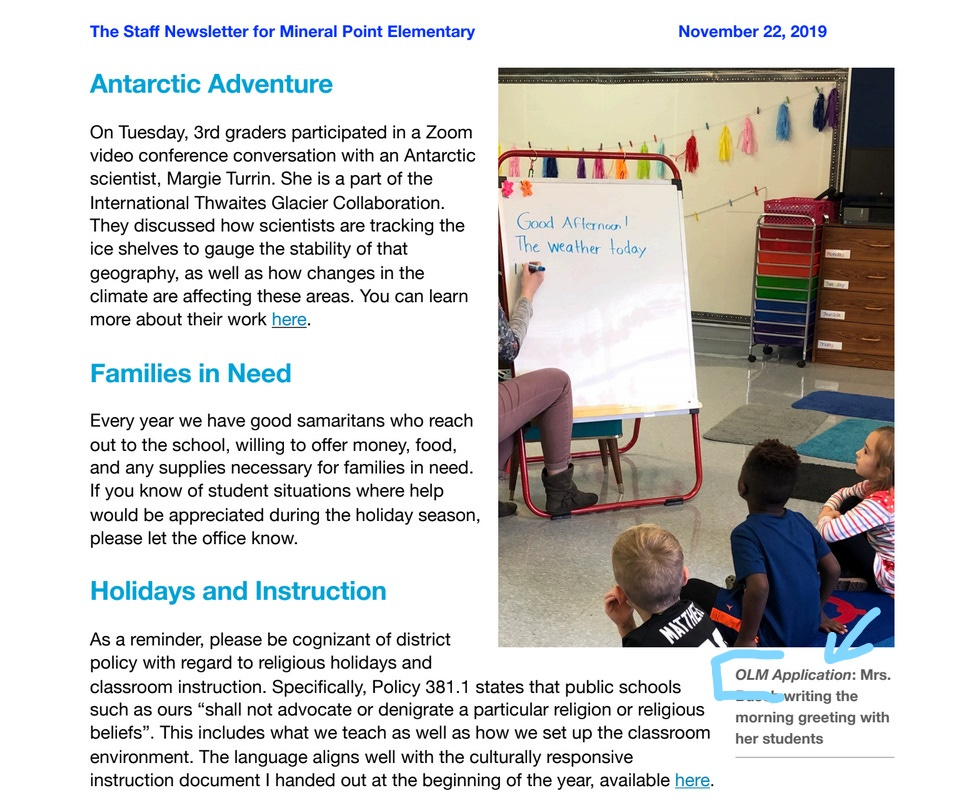

A teacher had a creative idea. “What if, in your weekly staff newsletters, you described the images you typically include from the classrooms as representing one of the ten areas of the framework?” It was implemented in my next edition (see bottom right).

Knowing how inconsistently newsletters are read, I also decided to differentiate the visual communications. For ten weeks, I replaced my traditional staff newsletter with short, one-minute-or-less videos that depicted a specific element of the literacy framework in action in our school. I often take pictures with my smartphone during instructional walks, so I had plenty of content to select from.

An additional advantage to the visual approach of communicating the framework was the recognition of teachers and students. The images were selected because they exemplified what we were looking for vs. what anyone wanted to see.

Clarity Precedes Confidence

One of the biggest reasons literacy leaders are reluctant to support teachers or provide feedback on their instruction is we don’t know if we are accurate in what we have to share. This is especially prevalent with literacy instruction. All of the debates around what “best practice” is can have a negative effect on our potential.

Instead of debates, we need dialogue. We need clear parameters as well as clarity in ideas brought up and what is heard. Frameworks, when developed collectively, based on what we know to be currently effective, and positively reinforced, can serve to better structure our conversations around literacy instruction that works for kids. A common language leads to clarity about excellence. It gives us the confidence to engage in continuous improvement.

References

Gabriel, R. E., & Woulfin, S. (2017). Making Teacher Evaluation Work: A Guide for Literacy Teachers and Leaders. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Routman, R. (2014). Read, Write, Lead: Breakthrough Strategies for Schoolwide Literacy Success. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Smith, N. B. (2017). A Principled Revolution in the Teaching of Writing. English Journal, 106(5), 70.

Wilson, M. (2006). Rethinking Rubrics in Writing Assessment. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.