In my previous post, I used the plate metaphor to convey how we have only so much time and energy for instruction, and how the pandemic disrupted our capacity for managing multiple variables. We were all online, or it was a blend. Teachers had to worry about whether their students’ Internet was working, if their computers were charged, if they had the right materials, etc. We had too much on our proverbial plates. We need to take something off. (Another metaphor that could work is juggling. I have heard it said, “Teachers can only juggle so many tasks.” or “I dropped the ball.”)

My recommendation is to reduce those lengthy units of study and simplify your literacy curriculum. In this post, I will go over each of the four steps. This approach leans heavily on previous works and ideas, which I will reference. It can work for literacy-only or integrated units of study.

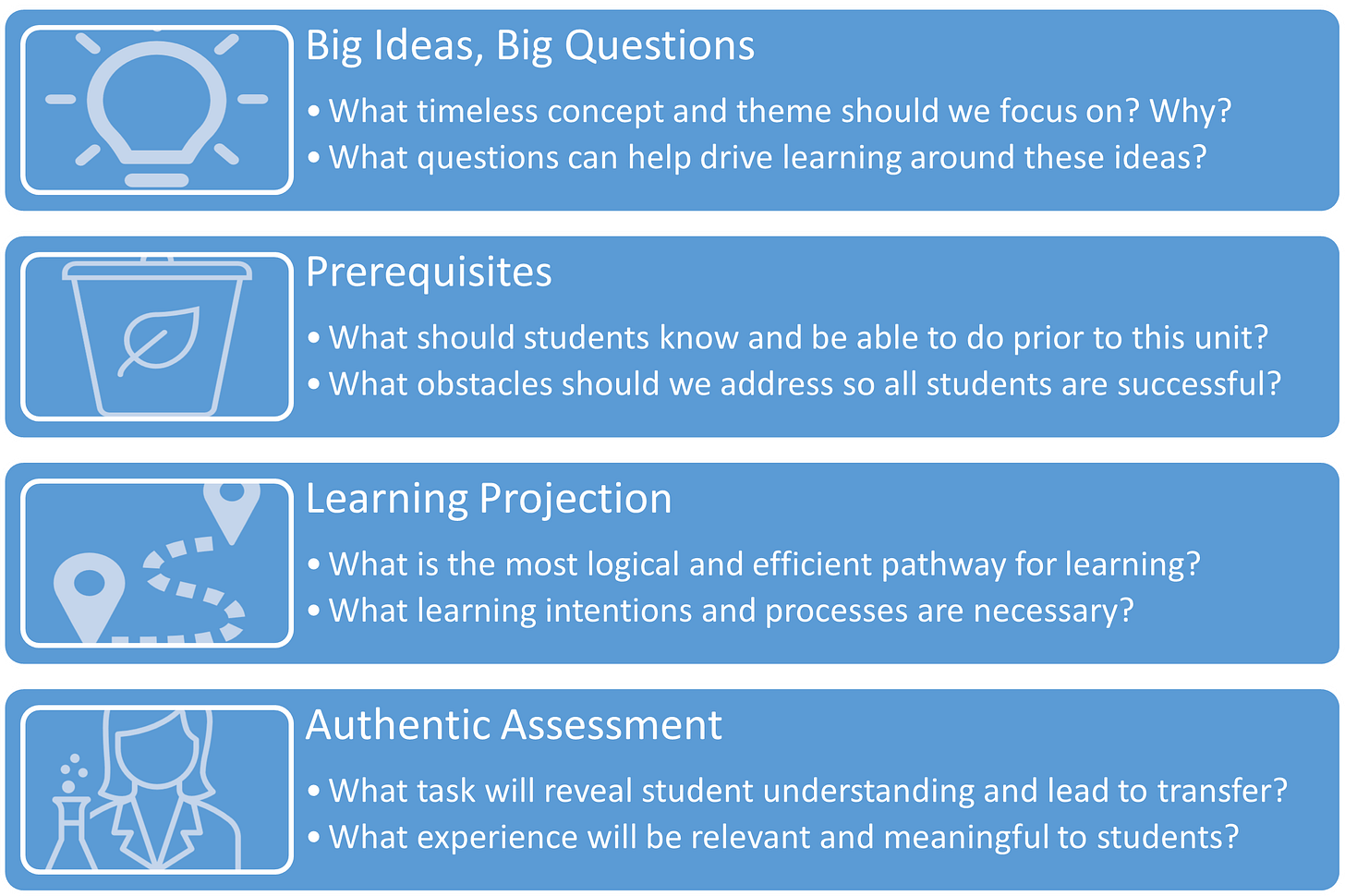

Simplify Your Literacy Curriculum Overview

This is a visual overview of the approach. The actual one-page template for housing a unit of study is available at the end of this post.

Step 1: Big Ideas, Big Questions

Many curriculum development approaches are founded on backward design, or planning with the end in mind first. Jay McTighe and Grant Wiggins of Understanding by Design fame formalized this work. As they note:

“Teaching is a means to an end, and planning precedes teaching. The most successful teaching begins, therefore, with clarity about desired learning outcomes and about the evidence that will show that learning has occurred” (2011, p. 7).1

So…what is worth learning? It is hard enough to identify “essential” knowledge and skills for today, let alone what our kids might need in their futures. David Perkins offers his take in Future Wise: Educating Our Children for a Changing World. Referring to an overarching focus of “big understandings”, Perkins admits that “there is no Holy Grail of an ideal universal curriculum – the same big understandings for everyone everywhere forever” (pg. 55).2

I prefer “ideas” over “understandings”, as the former connotes an openness to constructing meaning, while the latter may suggest a foregone conclusion. For instance, consider the concept of growth. Right away, what do we think? “Growth is good”, or maybe “continuous growth model” if you have been in education long enough. But is growth always good? A reasonable argument could be made against that position. As an example, unfettered capitalism without some form of regulation has caused problems in our economy and our environment, such as housing bubbles and water pollution, respectively.

Investigating this big idea of growth more critically naturally leads to big questions. For example, if I were designing an integrated unit of study around Westward Expansion and nonfiction, I might present the inquiry, “Is there always room to grow?” It feels like an open ended and provocative wondering, with the intent to question the competitive and zero-sum nature of our society.

Step 2: Prerequisites

This recommendation comes from Fenwick English’s book Deciding What to Teach and Test, as well as a related curriculum management training. Describing prerequisites involves what students should know and be able to do prior to starting a unit of study might seem redundant. “The students’ previous teachers should have taught them that.” – sound familiar? The reality is that kids come to our classrooms every day without the experiences and knowledge that will be helpful for them to succeed.

By identifying what should have been learned before, we become familiar with this information. We can then plan for addressing any knowledge or skill gaps in the beginning of a unit of study.

A starting point, but certainly not the only place to go, are standards. Look at the previous grade’s descriptions for the subject area(s). This process also better ensures that you are teaching toward an appropriate level of challenge.

Going with the Westward Expansion/nonfiction literacy unit, I might read both the social studies and the ELA standards for my state. In this situation (likely a 5th grade unit of study), I would read the 4th grade informational text standards. Here is one example:

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.4.2

Determine the main idea of a text and explain how it is supported by key details; summarize the text.

So, in my unit of study, I would list “determine main idea” as a prerequisite. Later, as I project out the series of lessons for the unit, I could think about how I might check whether students can apply this skill during instruction, such as reading and examining a primary document. We would be learning about how to determine two main ideas (a 5th grade standard), while at the same I can check to make sure they can determine one, or better yet model this process in the beginning as a review.

Step 3: Learning Projection

We can begin this curriculum development process at any entry point. The learning projection, or series of lessons, could be that place to start. Maybe you have a book stack of favorite titles that all have something in common.

This worked for me when I co-taught summer school in 2020. We used the following picture books to convey “growth mindset” through fiction and nonfiction.

Stuck by Oliver Jeffers

After the Fall: How Humpty Dumpty Got Back Up Again by Dan Santat

Emmanuel’s Dream: The True Story of Emmanuel Ofosu Yeboah by Laurie Ann Thompson and Sean Qualls

Rosie Revere, Engineer by Andrea Beaty and David Roberts

School’s First Day of School by Adam Rex and Christian Robinson

Martin’s Big Words by Doreen Rapport and Bryan Collier

Neville! by Norton Juster

Each Kindness by Jacqueline Woodson and E.B. Lewis

My Teacher is a Monster! by Peter Brown

Last Stop on Market Street by Matt de la Peña and Christian Robinson

Those Shoes by Maribeth Boelts and Noah Z. Jones

One Peace: True Stories of Young Activists by Janet Wilson

One aspect of this projection that seemed to make the most impact was developing a learning intention combined with a guiding question for each lesson. They framed our purpose for reading each book together, building our knowledge around growth mindset while also constructing meaning about the text. For example, we created the following intention + question for Neville!

Learning Intention: As learners, we will evaluate strategies used to solve a problem or tackle a challenge.

Guiding Question: What other ways could Neville have solved the problem?

My co-teacher and I leaned on these as we facilitated discussion with the soon-to-be 4th graders. (The learning intention framework comes from Made for Learning by Debra Crouch and Brian Cambourne.)3

Step 4: Authentic Assessment

This is the stage that I worry many teachers are spending too much time on. I know I did as a teacher. I would spend hours thinking about what unique and creative project the kids could engage in to show what they know and could do independently.

What I feel is most important is does the summative assessment give students the opportunity to demonstrate understanding and transfer? In other words, can they do it on their own?

Grant Wiggins’s book Educative Assessment (which I found at a university free library) was helpful for me in this area. It is out of print but quite good if you can get your hands on a copy. Anyway, Wiggins offers a clear example for thinking about how to authentically evaluate student learning at the end of a unit or a lesson.

He described a high school technology teacher’s assessment center. In it were different kinds of welds: one good, one excellent, one poor. This teacher would instruct students how to make a proficient weld, but the students had to determine their current skill level by comparing their work with the examples provided. Students received instant feedback for improvement.

Thinking about our 4th graders, we set up the authentic assessment task of each student selecting one thing they wanted to learn or to improve upon and then develop a plan for success. We taught them how to set a goal, consider obstacles, and decide how they would demonstrate their learning.

If this were the literacy/social studies unit on Westward Expansion, the students might be asked to write an essay that highlights one aspect of this era as the introduction, and then compare it to a current event of a similar concept (growth). We could publish these pieces in a local newspaper or on a classroom blog for an authentic audience. I also see opportunities for speaking and listening here, such as recording an audio version of their work for a newsletter and responding thoughtfully online to any comments on their piece.

Curriculum Writing is What Every Teacher Should Be Doing

I have wondered if all these curriculum approaches have become too complicated. It is almost set up as a cottage industry, in which a curriculum is not viable if it has not gone through the “experts’” process or purchased from a major educational publisher.

The truth is we teach the students we have in front of us. There is no way a process or resource is going to capture the imagination or interest of all your kids. Nor are these resources, as helpful as they might be, adapted for our current needs in a post-pandemic environment. Therefore, I believe you have to write the curriculum you want your students to experience. Knowing the connections you will make and the community you will create with your students, you are the only person who can.

Try this process out yourself - below is a link to a blank template for this work.

Join us next month for our annual summer book study. We are reading Cultivating Genius by Dr. Gholdy Muhammad. Read along with us while several educators will offer their contributions to the text on this site. And if you are not yet subscribed, sign up below.

Wiggins, G. P., & McTighe, J. (2011). The understanding by design guide to creating high-quality units. ASCD.

Perkins, D. (2014). Future wise: Educating our children for a changing world. John Wiley & Sons.

You can learn more about the authors’ work in this podcast I published with them last year.