Stop Blaming the Kids

How leaders can change the story schools tell

“What is not so evident, and is perhaps even controversial, is that educators’ personal belief systems may be the most powerful variables perpetuating learning gaps in our public school system.”

- Anthony Muhammad, Transforming School Culture (affiliate link)

Earlier this week, I was reviewing school district data with coaching colleagues in other parts of the state. One school had a 20% lower overall rate of reading proficiency than a neighboring school, and significantly lower than the state average.1

I was not familiar with this school. When asked what might be a root cause, a coach didn’t hesitate. “They blame the kids.” Staff apparently attributed the high percentage of students experiencing financial hardship plus chronic absenteeism as major reasons for low scores.

It’s the story teachers and leaders are telling others and themselves to explain outcomes they are seeing and where the school is going. Culture doesn’t come out of thin air. It is the “result of the collective actions of the people, artifacts, and routines that have shaped the current context” (Halverson & Kelley, 2017, affiliate link).

As a principal, I’ve observed that negative narratives within a school often flourish due to the nature of its leadership. Leaders implicitly endorse what they permit, including both formal and informal staff interactions. School stories, therefore, are shaped not only in official meetings but also in the less structured spaces within the organization.

It’s not hard to wallow in these complex narratives or admire problems instead of acting with collective agency. They don’t know where to start or have a vision of where they want to go.

Richard Halverson and Carolyn Kelley found through their research what makes the difference.

“Traditional leaders tell stories that fit with and reinforce the dominant themes of the existing stories. Transformational leaders tell stories that extend, reverse, or complement the existing stories with new narratives” (2017).

How can leaders begin to make this shift to telling a more inspiring and transformational story about their school?

Notice and name current beliefs and practices. Leaders can start this process by visiting classrooms and documenting what’s happening through a nonjudgmental lens. They can ask questions to understand the thinking behind teachers’ decision-making. This valuable data can inform an assessment of a school’s current reality.

Expect and model asset-based language. Moving away from deficit-based talk, such as referring to students as “Tier 3 kids” and blaming parents for student learning results, begins in formal interactions such as staff meetings. As an example, I have observed principals introduce shared beliefs, such as “We own the academic and behavioral outcomes of our students”. They ask the staff to respond with their level of agreement to statements like this, and then discuss as a group. Effective teachers influence colleagues to get on board with a “we can do it” attitude.

Become the chief communication officer. Instead of formal leaders feeling like they need to do all the work in changing the school’s narrative, they can instead highlight the positive things already happening in the building. For example, images of students reading independently and discussing texts with peers can be included in weekly staff newsletters. Quotes from classrooms that convey student engagement can be shared at board meetings and on social media. When principals and other positional leaders pay attention to and promote the positive, it changes the conversation schoolwide. These new ways of doing things become more of the norm.

Use data to drive leadership team conversations. Only placing a positive light on the school culture ignores the present challenges. An instructional leadership team comprised of the principal and teacher leaders can examine data and look for areas where students from historically marginalized groups are overrepresented. The most frequent challenges I’ve observed include students with disabilities, boys, and students of color showing less proficiency in reading compared to the student body. Effective teams ask: “What can we do to change the outcomes of this situation?” Solutions center on the system, for example, reducing the amount of pull-out intervention while increasing collaboration between classroom teachers and specialists.

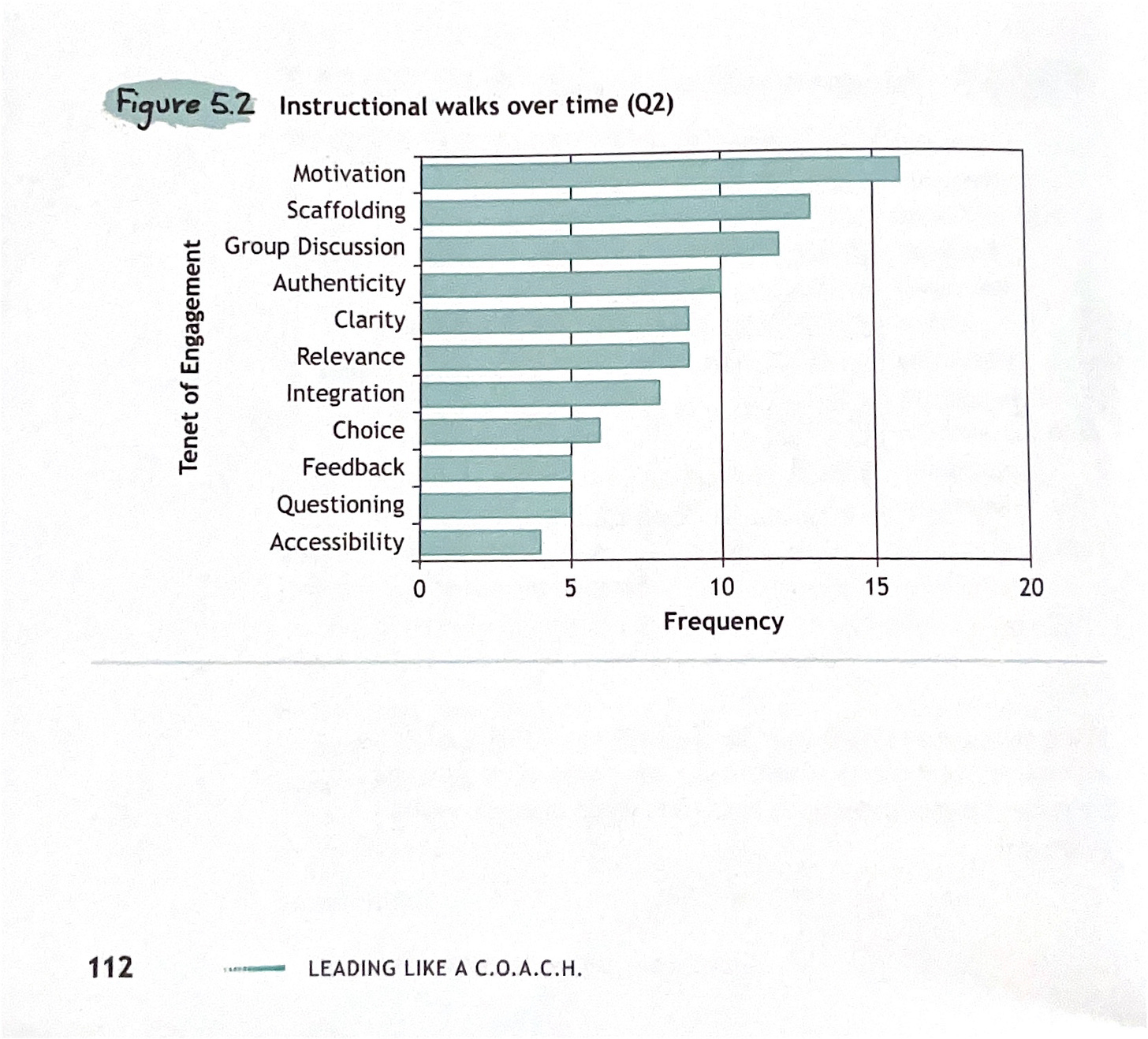

Track both practices and results. Too often, an improvement goal will be set, but an assumption is made that teachers are fine implementing new practices without support beyond traditional professional development. Through instructional walks, principals can capture what’s happening in classrooms and organize the data alongside student learning outcomes. As an example, as a principal, I presented my instructional walk data to our instructional leadership team. I graphed the frequency of observed practices we agreed were effective during every visit over one quarter (see image below). This information gave context to the challenges we were seeing around student engagement. Technical practices, such as scaffolding, were being implemented while more student-centered instruction (feedback, choice, questioning) lagged. It influenced our professional learning plan.

Celebrate growth and effort. A presenter at an educational conference recently noted that educators will commit to change when they see the light, not because they feel the heat. I have been guilty as a leader of focusing too much on improvement and not enough on celebrating the journey toward excellence. In addition to highlighting growth and effort in my communications, I also empowered staff to “toot their own horn”. For example, one school year, each teacher team hosted our monthly staff meetings in one of their classrooms. For the first five minutes, they got to share something that was working for them and their students. It was both a celebration and professional learning.

When I think back to that school where staff blamed the kids, I wonder what their story could become. The data won’t change overnight, but the narrative can shift today—from ‘these kids can’t’ to ‘here’s what we’re learning works.’ That’s where transformation begins: not in the test scores, but in the story we choose to tell ourselves about what’s possible.

Take care,

Matt

P.S. Subscribers can engage in this community beyond this post, for example, by joining us for a free webinar on December 4 on getting out of the office and into classrooms. Paid subscribers have additional benefits, including exclusive articles and the ability to post comments.

What I’m Reading

Living the Questions with Parker J. Palmer (Substack)

This weekly newsletter from long-time educator Parker Palmer is grounded and inspiring. Parker, a Madison, Wisconsin native, has always had a pulse on the lived experiences of practicing educators. In his most recent post (linked below), he explores the paradox of autumn as both an ending and a beginning.

Quoteable

I have changed a few details here to protect the district’s identity.