During our two-week homeschool experiment in January1 (we wanted to avoid any close contacts after the holiday break), we kept tabs with school. My son’s teacher invited us to read The Book Thief2. “That’s a tough book,” my wife commented, apparently recalling her own experience.

“How about I read it with you?” I offered my son. He shrugged. Not a “no”; maybe the best I would get from an 8th grader in the middle of a pandemic.

Reading has been somewhat marginalized during these times. People’s heads are cloudy. Some have trouble remembering simple things, like what it was they went to the grocery store for. At least part of our mind is thinking about the virus. This leads to “constant partial attention”. Reading needs our full attention. As good as a story might be, some mental commitment is expected on our end.

So, we set up a deal: he would read for a bit, then I would follow up and read up to his stopping point. In the margins, he would write down his thinking, and then I would follow up with responses to what he wrote. (Our copy was a garage sale find, a dollar or two.) My goal was to support his thinking. Not focused on whether he was right, but to affirm his ideas and pose questions to stretch ourselves.

Conversations in the Margins

“Often, when I'd take a peek in the students' books, I'd feel like I was witnessing something sacred, private, historical—and in many ways I was. This forum for dialogue found between the pages was one I helped create and curate, but it wasn't necessarily mine. When I read margin notes from a parent to a student that began, "Remind me to tell you about your Uncle Mike and the docks," I knew there was a shared significance taking place.”

- Callie Ryan Brimberry, “Conversations in the Margins”, Educational Leadership3

Teachers have long had students use the margins for jotting down their thinking around the text. These notes could be a conversation with the author, a placeholder for future in-person discussion with peers, or just to note a favorite line.

Sometimes these conversations in the margins can go beyond checking for comprehension. In Callie Ryan Brimberry’s classroom, students used margins notes in The Hate You Give by Angie Thomas as a reminder to talk to their families about a relevant issue. Their parents would sometimes write back.

I started by noticing what he noticed. For example, he made an inference about the relationship between Rose and Hans Hubermann (the foster family that takes in Liesel, the protagonist).

The Book Thief, pg. 72: “’You stink,’ Mama would say to Hans. ‘Like cigarettes and kerosene.’”

My son, in the margins: “It’s a wonder they’re still together.”

Me, in response: “She’s not very nice to him.”

After some back and forth of trading the book to read, I noticed he was writing less in the margins. Was he getting bored? Needed more support? I took the lead then and modeled some thinking.

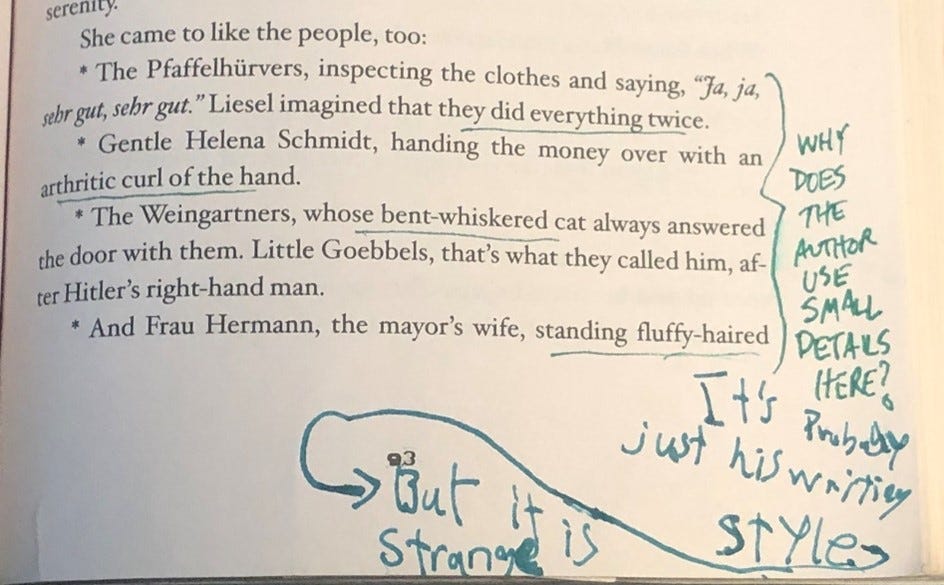

For example, I posed a question about the author’s intent with the unique descriptions.

Reflecting on my attempt at drawing his attention to the description, it felt forced.

Once our two weeks were up and my son went back to school in-person, he decided not to keep reading The Book Thief on his own.

Reducing Obstacles

We often define educational equity as giving students what they need to support their success. There are times it is defined as meeting students where they are. With what we know about education today, educational equity is also about breaking down the barriers to success.

- Chaunté Garrett, “Relevant Curriculum Is Equitable Curriculum”, Educational Leadership4

I have found that educators are almost always well intentioned, but they are not always helpful. Sometimes, despite our good intentions, we can inadvertently create more obstacles.

I began to read the book on my own. At first, he would not let me. “This is not a race, and it is okay if you don’t find it as interesting as I do.” I instead offered it as a read aloud every night. More times than not it is a “no”. But sometimes it is a “sure”. When I do read aloud, I keep my commentary to a minimum.

Backing off on the margin notes seemed right. I think if I were his teacher, I may have persisted with it, and he would have likely trudged along with me, doing the minimal required. There is tacit accountability in a school. Sometimes this can be a good thing as it forces us to commit to some new learning, and we may find it compelling.

But if the teaching itself is the obstacle, then it should be rethought. I am not against conversations in the margins. With the right book and in the right context, it can be an excellent replacement for more traditional assessments. And yet who are we serving, especially in the context of today? Always, always the student.5

Enjoyed this article? Share it with your colleagues.

The original title for this article was “Conversations in the Margins”, until I did a Google search and realized someone else already thought of it. Brimberry’s article validated this practice and expanded upon my initial thinking of what was possible.

Garrett’s article on a curriculum that is both relevant and equitable is so good. I’ve read it multiple times and plan to share it with my faculty.