The Importance of Background Knowledge for Self-Directed Learners

Don't assume students know what they need to know, regardless of age.

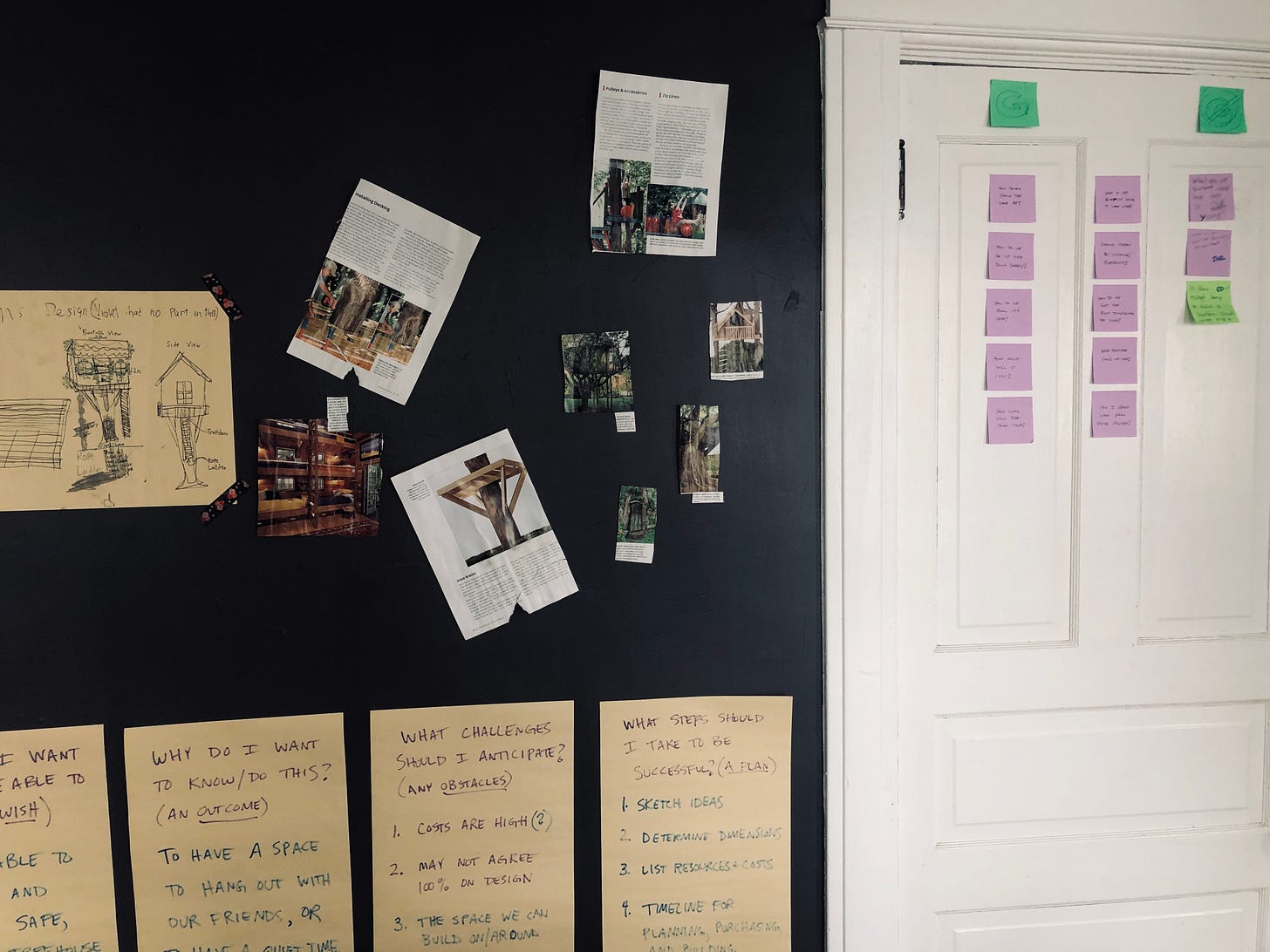

My wife noticed the cut out pictures with captions of treehouses on the wall. My kids and I were engaging in a collaborative Genius Hour project1, on how to design one of these outdoor structures in our backyard. “Is there enough trunk to build a platform around?” she asked, referring to one of the images the kids had found and posted.

“That’s a great question. You should post that next to the picture,” and I handed her a pad of sticky notes and a pen.

She held up her hands, palms out. “Oh no, this is your project.” After more cajoling, she accepted the pad and made her inquiry public.

I appreciated that she did not want to do too much of the work for the kids (Genius Hour projects are supposed to be more self-directed). But I suspect another reason for her hesitation was, like me, she did not know a lot about treehouses. Subsequently, she may not have felt confident in offering her thinking.

This reluctance touches on an important issue: All learners need background knowledge in order to engage successfully with new content or skills.

The Connection Between Background Knowledge and Engagement

Engagement is not just an emotional state. It goes beyond feeling a certain way about a topic or issue. Students also need to be able to cognitively commit to learning. This occurs more naturally when a learner begins to build upon their current knowledge base about the topic or issue.

With younger students, an assumption is often made that they lack background knowledge. The same stance is not always taken with older students. Because they talk more like adults and sometimes even act like them, we sometimes carry a bias that they have the necessary experiences and skills to engage successfully with content.

We are all susceptible to assumptions with regard to background knowledge. I once took a group of 5th graders to watch a movie at the local theater. The film was based on a book we had just read. Even though the theater was within walking distance of many kids’ homes, I was surprised at how many students had never stepped foot in one before. We had to explain during the movie that talking while the film was playing was frowned upon.

Regie Routman2 notes this issue in her book Literacy Essentials (134-135):

“I have often taken for granted that students have enough background knowledge and experience to know the basic vocabulary needed to understand a read-aloud book, a guided-reading book, or a self-selected book. Then a student will raise his hand and ask, ‘What does [that word] mean?’ Often it is a fundamental word, such as disappointment or energy. Time and time again, we assume that students - and teachers - have general knowledge and experiences about the world or instruction when they do not.”

With my two kids, a big assumption I made was that they knew enough about treehouses to come up with excellent questions about the topic to drive our collaborative inquiry. Yet when we started jotting our wonderings down, the questions were more surface level; most of them were able to be answered on Google.

“Well,” I observed. “We need to do some research.” I had two resources in my gardening and landscaping book collection. I pulled them out and let them pour over the texts, even cutting out images and descriptions for an idea board on our wall.

“For next time, think about some big questions, using information from these resources that you really want to know answers to.”

The resources and research must have helped. They came up with the following two questions:

What type of treehouse would look best in our yard?

What is the level of durability of our tree?

Without critical background knowledge, including resources selected by me, I doubt they would have been able to develop these deeper and more meaningful questions.

Not to say kids are unable to drive their own learning. The subject selected makes a difference. Cris Tovani3 encourages this careful choice of topic in her book Why Do I Have to Read This?. She sees how certain topics have characteristics that can “serve as Velcro that binds the content to memory so students can construct meaning” (95):

They are timeless and connected to a current event or issue.

They cultivate curiosity about why something is occurring or has happened.

There is an aspect of controversy connected to the issue that forces them to explore different perspectives.

New perspectives lead to stories that have powerful narratives driving the need to know.

The treehouse topic fits some of these criteria. It is current. The kids are curious about how something might happen. There was debate about the tree house design. But have we explored different perspectives on this? What did we not yet know?

People as Resources

The previous inquiries led me to another fact about background knowledge: not everything to be known comes from a book.

Just as educators make assumptions about what students know, we can also ignore efficient sources of knowledge: experts we can speak with in the field. Reading 10 books on a topic may not match a lifetime of learning that can be shared by one person.

We called two individuals in our community to help with our big questions. Ed, our neighbor, suggested an 8’ by 8’ square base. He had previously built several treehouses. “And if you want to save some money, there are people out there looking to have their sheds taken down. We could reuse that wood for free.” The kids agreed to those ideas. Joel, a local arborist, deemed the tree safe for building a structure around.

With our more formidable knowledge base, we developed a slideshow presentation with our treehouse proposal. (My parents were the audience via Zoom.) The kids spoke with confidence as they went through the slides. They successfully answered the questions thrown at them at the end.

Now they are helping us save up to purchase the hardware to start building in the spring. The more we delve into this topic, the more interesting it is becoming.

How can I ensure students have enough background knowledge4 to lead their own learning? Consider the following suggestions:

Search for a topic that will compel students to want to know more about it.

Engage the class in initial study and reflection to surface what is known, misconceptions, interests. Consider shared reading of multiple texts and engaged in structured dialogue about them. Use what students say to build your own background knowledge about them and to inform future instruction.

Use an instructional framework that allows for responsive instruction, i.e. providing more or less scaffolding based on students’ current needs.

Visibly monitor progress on projects, such as a Genius Hour5 wall, so students and you can quickly gauge the learning plan.

Invite community members to join these types of projects. Go beyond the “guest speaker” role and ask them to be active contributors to student learning. For example, students might generate a list of questions prior to a visit that this person would be able to address.

Enjoyed this article? Share it with your colleagues.

I previously wrote about our “learning from home” project here. The kids are now back in the building. Home schooling is fun, but challenging!

Regie Routman’s latest book is a necessary resource for every teacher. Check out her podcast page for more information about her work, including my conversation with her last spring.

In her study, Dr. Courtney Hattan found that relational reasoning was a more effective approach for developing background knowledge than annotation or graphic organizers such as the KWL. Relational reasoning is “the ability to derive meaningful patterns within texts or other information streams”, for example asking students to determine how ideas from the text are similar or different than other content or current background knowledge.

Later this month, I will be posting my conversation with Denise Krebs and Gallit Zvi, authors of The Genius Hour Guidebook. If you haven’t yet, sign up to this newsletter today to catch the podcast episode.