The Leadership-Reading Brain

Is literacy a tool for empowerment or oppression in your school?

We introduce literacy practices and programs in our schools assuming they are value-added. These assumptions are often the product of cognitive errors such as anchor bias (you want to stick to your first estimate, or to what you have been told) and ease of representation (you think an explanation you can understand is more likely to be true than one you can't).1 A resource states it is aligned with the science of reading, and we believe it to be true without investigating further.

What is true is that nothing is infallible. As scholar David Kirkland noted, the only thing that every study cited in the What Works Clearinghouse has in common is that nothing works.2 The process of teaching and learning is too dynamic and contextual for any instructional practice or program to offer a guarantee.

I’ve sometimes gone one step further in this line of thinking and suggested that all teacher-directed instruction is an intervention. When we set up guided reading groups and similar teaching structures, we are potentially interfering with a student’s naturally learning process. It’s something I learned after reading Brian Cambourne and Debra Crouch’s Made for Learning: we are at our best when we create the conditions for learning. When we honor these natural learning conditions, we foster student agency and decision-making.

Yet too often, our well-intentioned interventions do the opposite. There are ramifications beyond skill development. When we make decision as leaders as to what to read and learn and how, we disempower our teachers and students. It’s essential that our students learn how to make decisions as learners. Being skilled readers and knowing “stuff” is no longer enough. Our world needs empowered readers, writers, thinkers. These outcomes are especially important for students from historically marginalized communities who regularly experience systemic barriers in society.

Grand Challenges

Dr. Alfred Tatum, a professor in the School of Education at Metropolitan State University of Denver, framed this issue as four “grand challenges” at a recent education conference:

Celebrating speed and accuracy at the expense of deep reading

Confusing reading focus with actual growth as readers

Conflating progress monitoring with understanding and wisdom

Choosing short term reading success over lifelong reader agency

These challenges can be attributed in part to what is largely considered “foundational” in reading: namely, phonics. How did we arrive at this consensus, where isolated word/sound/letter study became the starting point for building a reader?

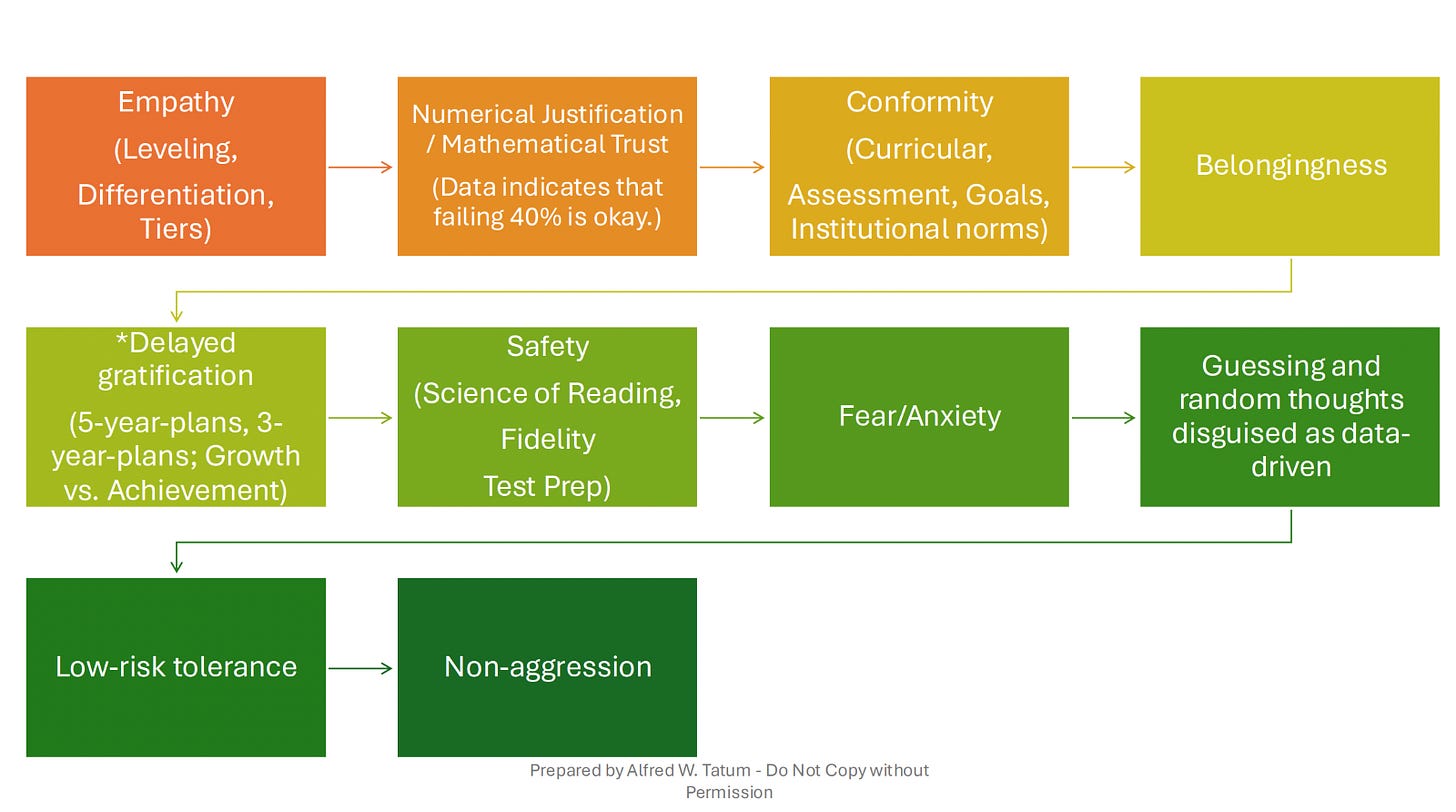

Dr. Tatum offers us a map that highlights the pathway we have taken up until today.

I have walked this pathway as a teacher starting in 2000. I taught from a place of trust and confidence: knowing my students and having the support of leadership to make instructional decisions on their behalf. But this empowerment wasn't leading to equitable outcomes for all, likely due to a lack of investment in time and funding for excellent teacher professional development.

So, in the name of consistency, our systems sought out conformity. Leaders at all levels called for standardization and accountability. I will be honest: I wasn’t totally against it. But also at the time, I was unsure about my beliefs around literacy instruction. Conformity sounded good if it meant we were all providing excellent instruction for our students.

What we gave up in autonomy and professionalism was a false promise of proficiency for all of our students, i.e. No Child Left Behind, by a certain date. It felt safe to stick to the script. The trade in that delayed gratification was choice and voice in what to read and write about, both teacher and student. This revealed the downside of safety: we weren’t reading texts that pushed our thinking and perspectives in new and unexpected ways. Students’ writing became more formulaic and less fun to read. Subsequently, our conversations during the literacy block were more bland and less engaging. People were unsure what to speak up about because the new curricula gave us little to speak to.

Developing a Leadership-Reading Brain

According to Dr. Tatum, how people learn to read (and lead) is a dynamic process.

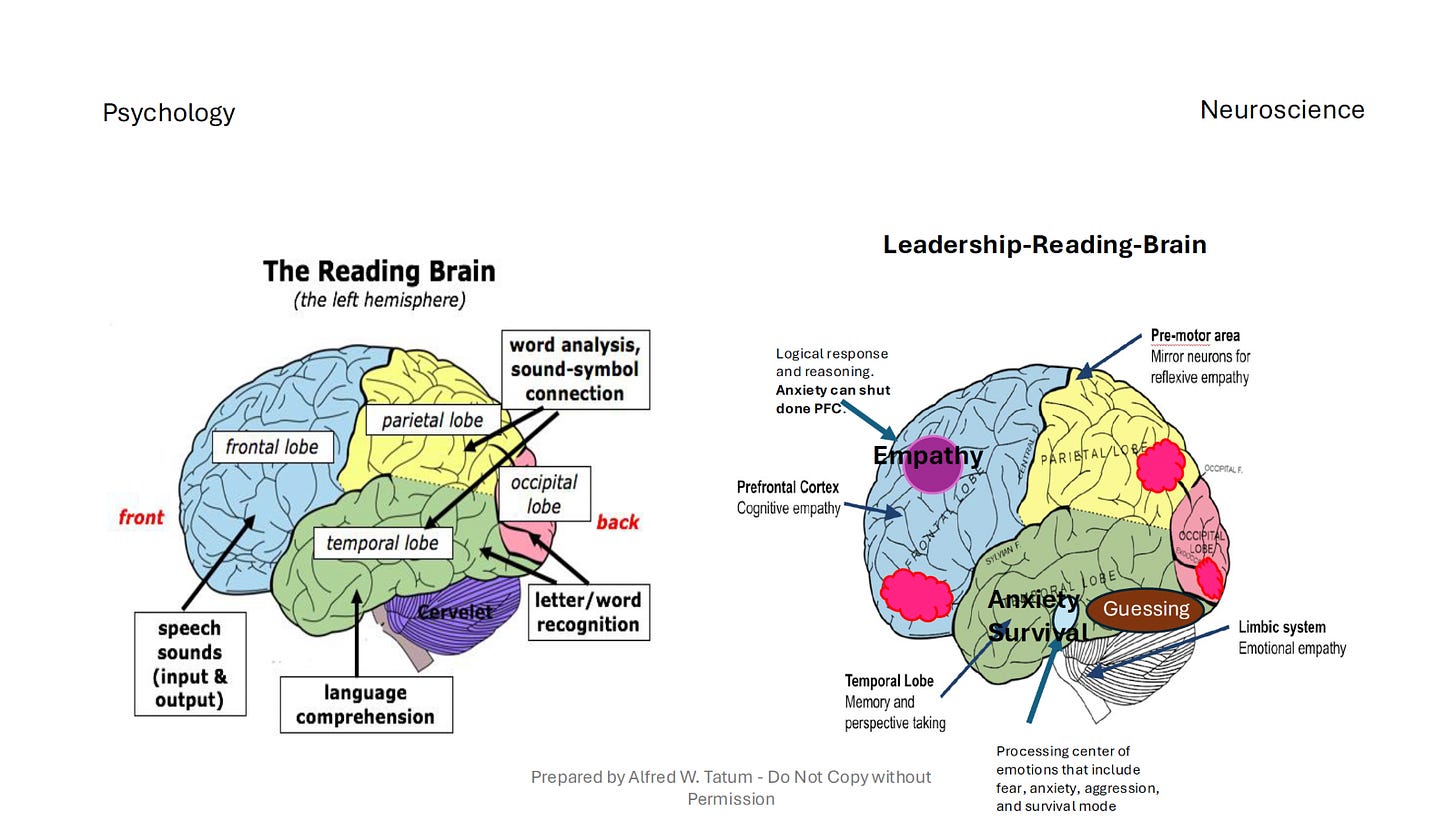

With reading, multiple areas of the brain work together in a distributed manner, interactively converting symbols and sounds into words that convey meaning, originating from the writer and constructed by the reader. The prefrontal cortex helps regulate attention and working memory as these networks coordinate, especially for emerging readers. As reading from a skill/strategy perspective becomes more automatic, less executive functioning is needed.

A leadership-reading brain requires a somewhat similar distributed way of thinking. Obviously, our goal isn’t to learn to read; it’s learning to lead. We employ different regions of the brain to match the complexity of our tasks. For example, a leader analyzes a data set of their school’s current reality for teaching readers. They empathize with the students who are struggling, often kids from historically marginalized communities. They visit classrooms and assess the professional needs of the faculty. They engage in perspective-taking with teachers, “making guesses” as to how best to support each person.

If a leader experiences resistance to implementing new ideas, they draw upon their prefrontal cortex to self-regulate their own emotions in order to remain curious and not judgmental during a coaching conversation. The coordination of their analytical, social-emotional, and executive networks supports a more objective and compassionate response to continuous improvement efforts. The more leaders engage these multiple networks via coaching and mentoring, the more automatic these interactions become. Conversely, when they rely on one network - all data and no empathy, for example – they struggle to develop leading proficiency.

Four Questions to Help Shift Perspectives and Priorities

Coming back to the original question, is your leadership empowering or oppressing literacy teaching and learning in your school?

Dr. Tatum offered several questions to the audience to help facilitate reflection and growth. Here are four that stood out to me, paraphrased through my understanding:

Are your current beliefs and practices perpetuating or disrupting the status quo? Are you and other building leaders authorizing and cementing hierarchies, for example intervention approaches that serve teachers’ comforts over students’ needs? You can study this by examining schedules and determining what percentage of supports pull students out of the classroom.

What is your influence on teachers’ decisions in the classrooms? It’s a humbling experience to accept that we as leaders do not have a direct impact on student outcomes.3 We work through teachers to improve classroom literacy instruction. How are you providing positive support along with health accountability? What measures are you using to communicate feedback and empower teachers as decision-makers?

How does your school interpret research and implement evidence-based instructional strategies? There needs to be some type of gatekeeping of what filters into the school culture and becomes a part of the collective practice. Conversely, effective practices that don’t initially stick schoolwide require scaffolding and reinforcement. This is where your instructional leadership team can develop a process for inclusion/exclusion of research that informs professional development plans.

Are you an inhibitor or a conduit for achieving schoolwide excellence? What we don’t say or do can be as influential as what we say or do. For instance, when you repeatedly see worksheets used in one classroom during your instructional walks, not addressing this issue with the teacher communicates to them and their colleagues that this is an acceptable practice. It perpetuates inequitable outcomes and erodes trust. As a mentor once shared with me, “What we permit, we promote.”

When we position each and every student at the center of our decision-making, our reading-leadership brain will always default to empowering them as literate individuals. That is achieved when we likewise empower our teachers through a high-expectations, high-support professional environment. In this way, literacy becomes what it should always be—a tool for liberation, not limitation.

Robinson, K. S. (2020). The Ministry for the Future: A novel. Orbit.

Kirkland, D. (2015). NCTE National Conference. Keynote

Grissom, J. A., Egalite, A. J., & Lindsay, C. A. (2021). How Principals Affect Students and Schools. Wallace Foundation, 2(1), 30-41.

Matt,

Bravo! One of your most powerful writings, ably supported by the unique findings and beliefs of Dr. Alfred Tatum and his impact on your thinking. Your writing is thought-provoking, scholarly, and practical. Every leader --and teacher too--would benefit from reading your post and discussing it as part of PD early on in the school year. You make visible for the reader what true empowerment is and why it's a necessity for optimal leading, teaching, and learning at all levels.