“Storytellers know that every story is at least partly a lie. Every story could be told in four different ways, or forty or four thousand. Every emphasis or omission is a kind of lie, shaping a moment to make a point.”

- Naomi Alderman, The Liar’s Gospel

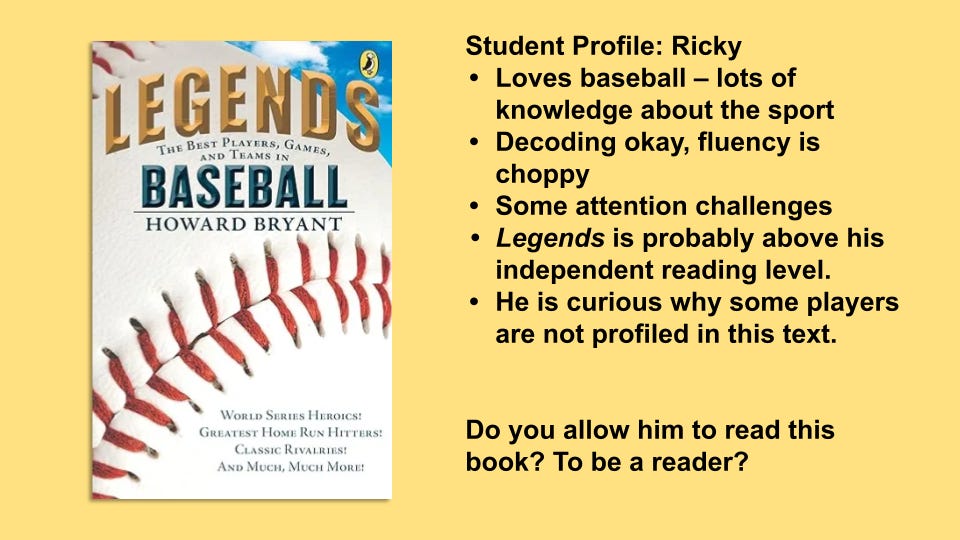

During an instructional walk last school year, I conferred with a 5th grader, Ricky.

He loves baseball. Legends was open in his hands. As I observed Ricky reading, he took a long pause: staring into the empty space in front of him, possibly deep in thought.

I interrupted his thinking. “So, what’s happening in your story?” He looked at me, just realizing I was in his proximity, and shared with me what was on his mind. “I was just thinking about why Aaron Judge wasn’t in this book…”

As Ricky went on, he explained that Aaron Judge currently plays for the Yankees. Judge is a very good player. He considered this knowledge with what he knew about baseball in general. “You can’t just become a legend. Time has to go by.”

I asked Ricky if he was aware of the timeline this book followed. He wasn’t sure. “Could we take a look at the table of contents?” I inquired. Glancing at the topics, it became clear that the athletes this book covered played up until the mid-1980s.

Not resting on just answering a question, I asked Ricky if Aaron Judge had the potential to become a legend. His eyes lit up. “Oh, for sure. Look, here are the statistics for some of these other players….” He went on to share Judge’s statistics in comparison to the career numbers of some of the legends.

Listening to him read more of the text, his fluency was a bit choppy. The text was likely above his independent reading level. His attention span was not strong. Yet his motivation to read the book, along with his background knowledge about baseball, helped him succeed.

In this classroom, Ricky is a reader. He has the authority to choose books he wants to read. He is supported by the teacher through conferring, along with small group instruction and opportunities to engage with easier, high-interest texts.

In other classrooms, Ricky might not be seen as a reader. If the school or a teacher believes that reading is simply the ability to decode and recognize the meanings of words, in that context Ricky may be prevented from having this book in his possession. He could take it home and read there. In school, he must always have texts in his hands that he can read with 95%+ accuracy. Only then is Ricky reading.

To summarize, here is an abbreviated reader profile of Ricky.

How would Ricky be seen in your school? How would Ricky see himself?

These are the type of dilemmas teachers have to contend with regularly.

We want kids to be successful as readers. How do we define what it means to be a reader? Is it how well they can “crack the code”? Or do we define it more broadly - not just as how well someone reads, but also in their engagement with reading and through their identity as a reader?

How I deconstructed this dilemma describes a binary approach to teaching readers. Either Ricky can read Legends, or he cannot.

This may be the primary problem with the push for a science of reading agenda in our schools. There is no room for nuance, to imagine third, fourth, and fifth ways of meeting readers where they are.

Consider the possibilities:

The teacher finds the audio version of the text and Ricky can listen to it while reading the text. The content is now full accessible.

Ricky agrees to spend half his independent reading time with texts that he can read with 95%+ accuracy. In this plan, he is successful as a reader both from a skill perspective and from an engagement perspective.

Ricky becomes the “sports authority” of the classroom. He is put in charge of the classroom library related to athletics and biographies. When a student needs to find a new text in these genres, Ricky is the first person to talk to.

I recently watched The Right to Read. I also listened to all six episodes of Sold a Story.

There were inaccuracies, as well as a lack of providing a full picture of this issue.

Where I struggled the most was how the producers reduced reading down to a simple process. In their world, reading is just synapses firing between systems in the brain, working to translate some squiggly lines into symbols that hold meaning. This ignores all of the other research showing how motivation and engagement, self-efficacy, and metacognition also influence how well one reads and identifies as a reader. To omit this literature out of the science of reading conversation is, as novelist Naomi Alderman describes it, “a kind of lie”.

This limited view of reading is not just disingenuous. It is also dangerous. Painting a picture of reading (and writing) as a primitive way of communicating basic ideas disregards how language has been used to oppress and harm others. If students are not equipped to see how being literate goes beyond decoding and word recognition, they are vulnerable to disinformation and other abuses of media and power.

This synthesized version of teaching readers can lead to depersonalization within reading instruction. The reader is taken out of the reading equation. This cleans things up from a teaching standpoint. But it also pushes out the complexity that comes with becoming a reader, a writer, a thinker. Mistakes are the entry points for learning. We can become better versions of ourselves through our challenges.

Students’ identities as readers are intertwined with the intricacies of learning to read. We can’t achieve one without the other.

The human factor - differences among individuals and groups, their practices, their interactions, and the unpredictability that accompanies being human - disrupts the possibility of narrow and universally applicable solutions for helping all students become readers.

- Compton‐Lilly, C., Mitra, A., Guay, M., & Spence, L. (2020). “A Confluence of Complexity: Intersections Among Reading Theory, Neuroscience, and Observations of Young Readers.” Reading Research Quarterly, 55, S185-S195.

To be clear, students have the right to learn how to read. What I am talking about here is reading in its most basic form: decoding, language comprehension, word recognition, etc.

Just as important, students have the right to be a reader.

This is a concept revisited often in my team of systems coaches throughout the state:

The only people who have the right to be in public schools are the students.

Teachers, leaders, coaches…we do not.

This is where teachers come in. They are the chief storytellers of their classrooms. They influence how students craft their own narratives as readers, writers, thinkers. Whether Ricky is allowed to read Legends during school shapes how he views himself as a reader, as someone who has or lacks authority and agency in his reading life.

In closing, a few questions for you as you work with your readers:

Through what lens are you making instructional decisions: trusting your students or controlling the outcomes?

What stories are your students telling themselves about who they are as readers? How do you know?

What percentage of your instructional time is devoted to teaching? To learning? (Yes, these are two different things.)

How has your own history as a reader influenced who you are as a teacher of readers? What do you believe based on this identity?

Professional Learning Opportunities

I just finished hosting two sessions on equity projects at the Wisconsin State Reading Association Conference. It’s an excellent literacy experience, rivaling any other state’s convention.

On Tuesday, February 13 at 5:30pm CST, I will be speaking with Michele Caracappa, educator and writer at Reading to Lead. We will have a conversation around reading policy, equity, and justice. Full subscribers can RSVP here.

All educators can join my upcoming course on how to give feedback that improves classroom instruction. Enroll or join the wait list here.

I’ll be facilitating a webinar through WSRA on coaching literacy on Tuesday, March 19, 2024 at 6:00 PM to 7:30 PM CST via Zoom. Register here.

Our next book club is How to Become a Better Writing Teacher by Carl Anderson and Matt Glover. Full subscribers can join the conversation via Zoom on the following dates; look for an email soon to RSVP.

Tuesday, March 12, 5:30pm CST (Carl and Matt will join us!)

Tuesday, April 16, 5:30pm CST

Tuesday, May 15, 5:30pm CST