Using Picture Books to Develop Critical Thinking

“We have a vaccine for the pandemic. Where is the vaccine for climate change? Where is the vaccine for conflict? Where is the vaccine for inequality and racism and prejudice and species loss? We all know what the vaccine is against these things. It is called education.”

- Simon Anhalt1, author of The Good Country Equation.

With all the talk about phonics, we might forget about the purpose of reading and why it is important. It seems unwise to separate the two. To address one area out of context of the other might help simplify our jobs as teachers. Yet it can ignore the complexities of reading at our students’ expense.

We can promote authentic literacy experiences with opportunities to develop critical thinking. Critical thinking can be defined as “the ability to understand why things are the way they are and to understand the potential consequences of actions”2. It includes having the capacity to slow down one’s thinking, to question what is initially offered as true, and to consider other theories for what we observe.

Just “being” in school over time does not necessarily lead to developing critical thinking. One study found that fact checkers for news outlets were more adept at finding false information online than professors and graduate students.3 Learning to read is more than just acquiring basic skills and knowledge.

We can develop critical thinking at any age by guiding discussion while reading aloud picture books.

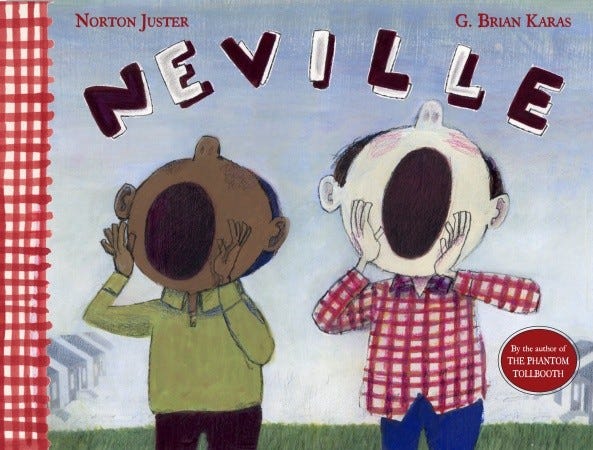

Neville by Norton Juster

I hosted a demonstration lesson on Zoom for our virtual teachers this year. My goals were:

a) to model questioning and paraphrasing so students think more deeply and critically about a text, and

b) to show that complex thinking and learning can occur in online spaces.

I started by presenting an authentic inquiry:

“How do we best make friends?”

About a dozen virtual students, grades K-5, offered their initial thinking.

“Ask them to play with you.”

“Be nice to them.”

As I read aloud the story, we started to suspect that the main character was not who he seemed to be.

“Do you agree with his approach to making friends? Why or why not?”

This open question was followed by a lengthy pause. Finally, one student related her experience with developing friendships to the story’s situation.

“When I came to this school, I did not know anyone. But I met Alleigh and Callie and over time we became friends.” She added specific examples of her friendship-development process.

I followed up with a paraphrase. “So, part of making friends is to keep trying, to show up and to be persistent and kind?” The student nodded. More students then related their knowledge to the discussion. “You should not change in order to make friends,” advised another. “Just be yourself.”

When the story ended, I asked them what they thought of the ending. “Did you like it or not?” (Warning: Spoiler alert)

One student shared their confusion. “I don’t understand why the author had Neville yell out his name, like he was someone else. I don’t get it.”

Another student responded. “I think the author wanted you to know that Neville didn’t know what to do, so he did the first thing that came to his mind.” A third student concurred. “Yes, that makes sense. The author is pretty creative.” A fourth student added on. “Yes, but I don’t know how I would feel knowing that Neville had tricked us. I might be upset for a while.” Lots of nods.

I summarized our conversation. “It sounds like there are multiples ways to view the author’s intentions and to feel about this story. People can have different opinions and positions about the same thing. Can we agree on this?” Many nods.

Beyond the Basics

“How do we leave our children in a better state to fix the world, instead of leaving our world in a better state for our children? That seems to me to be the better question.” – Simon Anhalt

So much of reading instruction is focused on developing foundational skills and supporting student comprehension of the text. This typically means getting to the right answer.

Yet in our complex society, dualistic thinking should be the floor and not the ceiling for student success as readers. One outcome we can anticipate when consistently developing students’ capacity for critical thinking is social imagination. Selecting quality fiction like Neville is a key to supporting this instruction.

Johnston and colleagues break down the concept of social imagination.4

“The social imagination has three components: (1) perspective taking (the ability to think about what others are thinking and feeling, (2) empathy (the mostly automatic ability to experience others’ feelings), and (3) empathic concern (the disposition to act to help others in response to understanding their experience). Each of these components is necessary for the development of a strong democracy but also for human development. (pg. 138)”

Picture all our students demonstrating these abilities and dispositions as adults. Can we agree on this?

What books beyond Neville5 would support deeper conversations in classrooms? Share some of your favorite titles.

Simon Anhalt presented his work on behalf of the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) recently; video recording available here.

Rick Hess, “The Stanford scholar bent on helping digital readers spot fake news”, AEI (h/t Regie)

Engaging Literate Minds was our book study selection for Summer 2020. You can read all posts from contributors here.

I will be co-leading a book club conversation around Neville on Sunday, April 25 with Choice Literacy. Join us!